STROMBERG, J.; HIBBARD, J. T. (eds.) The History of Isaiah: The Formation of the Book and its Presentation of the Past. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2021, 599 p. – ISBN 9783161560972.

Diz o Prefácio:

O livro de Isaías é um produto da história. A natureza dessa história e o que significa que Isaías é um produto dela, dificilmente são questões de consenso no campo dos estudos bíblicos. Isso deveria ser esperado. A história é complexa. E provavelmente confunde, mais frequentemente do que confirma, as tentativas de entendê-la completamente. Mesmo assim, a pesquisa isaiânica colocou o dedo no cerne do problema metodológico. No cerne de uma compreensão histórica deste livro profético está uma consideração da palavra “história” em duas aplicações distintas, mas relacionadas.

Primeiro, quais processos históricos levaram à forma final do livro? E segundo, que tipo de representação histórica o livro oferece ao leitor?

A primeira questão examina como Isaías se tornou um livro. A última inspeciona sua apresentação da história, uma apresentação complexa envolvendo diversos modos de exposição (perspectiva profética, reflexão poética sobre o presente e relatos em prosa do passado). Esta história envolve as tradições bíblicas e envolve as relações de Israel com os grandes impérios do Antigo Oriente Médio, um passado já distante do ponto de vista da forma final do livro. Para a maioria dos estudiosos, responder a uma pergunta envolve perguntar a outra, a diacronia do livro sendo relacionada à apresentação da história encontrada nele e vice-versa. Para entender melhor a história de Isaías, este volume de ensaios se dedica a essas duas linhas de investigação e seu relacionamento.

O volume foi dividido em três partes.

A primeira fornece um conjunto de ensaios dedicados às questões metodológicas envolvidas no exame da diacronia do livro de Isaías e sua apresentação da história. Nesta seção o objetivo é permitir a reflexão sobre os procedimentos analíticos pressupostos nos estudos diacrônicos e sincrônicos apresentados pela segunda e terceira partes do volume.

A segunda parte oferece uma consideração da história de Isaías à luz das tradições bíblicas. De uma perspectiva histórica, essas tradições permanecem indispensáveis, até mesmo fundamentais para a compreensão da história de Isaías. Isso é verdade em relação à diacronia textual de Isaías, bem como à sua representação histórica. Aqui, essa relação é examinada em relação aos diferentes estágios na formação textual de Isaías e da Bíblia Hebraica.

A terceira parte deste volume investiga a história de Isaías por meio de um foco nos impérios explicitamente mencionados no livro. A justificativa que norteia a seleção dos impérios aqui investigados (Assíria, Babilônia e Pérsia) deriva do papel fundamental desempenhado pela interação de Israel com essas nações na formação do livro em cada um de seus principais estágios.

Ao estruturar o volume dessa forma, esperamos que o leitor perceba o todo e não apenas as partes. Teoria e prática estão ligadas tanto quanto as histórias da Bíblia e do Antigo Oriente Médio. Assim, nosso objetivo ao compor este volume é fornecer ao leitor um tratamento metodologicamente informado deste tópico central – a história de Isaías – pois abrange todo o livro, se relaciona com as tradições da Bíblia e emerge das complexidades da vida no Antigo Oriente Médio.

Além disso, nosso objetivo ao selecionar colaboradores era fornecer um tratamento representativo deste tópico complicado, um que refletisse as diferentes perspectivas em jogo no campo dos estudos bíblicos hoje. Em um empreendimento deste tipo é, talvez, inevitável que lacunas na cobertura, no entanto, permaneçam.

Veja o sumário do livro em pdf, clicando aqui.

Jacob Stromberg é Professor de Antigo Testamento na Universidade Duke, Durham, NC, USA.

J. Todd Hibbard é Professor de Estudos Religiosos na Universidade de Detroit Mercy, Detroit, USA.

Preface

The book of Isaiah is a product of history. The nature of that history and what it means that Isaiah is a product of it are hardly matters of consensus in the field. This should be expected. History is complex. And it probably confounds, more often than it confirms attempts to understand it completely. Even so, Isaianic scholarship has put its collective finger on the crux of the methodological problem. At the heart of an historical understanding of this prophetic book lies a consideration of the word “history” in two distinct but related applications. First, what historical processes led to the book’s final form? And second, what kind of historical representation does the book offer to the reader? The former question examines how Isaiah became a book. The latter inspects its presentation of history, a complex presentation involving diverse modes of exposition (prophetic forecasting, poetic reflection on the present, and prose accounts of the past). This history engages the Biblical traditions and it involves Israel’s dealings with the great empires of the Ancient Near East, much of which lay in the past from the point of view of the book’s final form. For most scholars, answering either question involves asking the other, the diachrony of the book being related to the presentation of history found therein and vice versa. To understand better the history of Isaiah, this volume of essays devotes itself to these two lines of inquiry and their relationship.

To this end, the volume is divided into three parts. The first provides a set of essays devoted to the methodological issues involved in examining the diachrony of the book of Isaiah and its presentation of history. In this section, the aim is to enable reflection upon the analytical procedures presupposed in the diachronic and synchronic studies presented by the second and third parts of the volume. The second part offers a consideration of the history of Isaiah in the light of the Biblical traditions. From an historical perspective, these traditions remain indispensable, even foundational for understanding the history of Isaiah. This is true regarding Isaiah’s textual diachrony as well as its historical representation. Here this relationship is examined in relation to differing stages in the textual formation of Isaiah and the Hebrew Bible. The third part of this volume investigates the history of Isaiah by means of a focus on those empires explicitly mentioned in the book. The rationale guiding the selection of those foreign empires here investigated (Assyria, Babylon, and Persia) derives from the pivotal role played by Israel’s interaction with these nations in the formation of the book in each of its major stages.

In structuring the volume this way, we hope the reader will perceive the whole and not just the parts. Theory and practice are bound together every bit as much as are the histories of the Bible and the Ancient Near East. Thus, our aim in putting this volume together is to provide the reader with a methodologically informed treatment of this central topic – the history of Isaiah – as it spans the whole book, relates to the traditions of the Bible, and emerges out of the complexities of life in the Ancient Near East. Moreover, our goal in selecting contributors was to provide a representative handling of this complicated topic, one reflecting the differing perspectives at play in the field today. In an undertaking of this scope, it is perhaps inevitable that gaps in coverage will, nonetheless, remain.

Jacob Stromberg, born 1974; D. Phil. Oxford; since 2011 Lecturer in Old Testament at Duke University.

J. Todd Hibbard, born 1968; PhD University of Notre Dame; since 2011 Associate Professor of Religious Studies, University of Detroit Mercy.

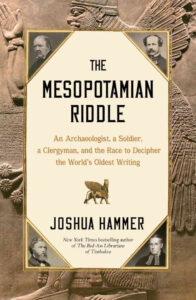

Por volta de 3.400 a.C. — enquanto os humanos se agrupavam em complexos assentamentos urbanos — um escriba na cidade-estado de Uruk, com suas muralhas de barro, pegou um estilete de junco para imprimir pequenos símbolos na argila. Por três milênios, a escrita cuneiforme (em forma de cunha) registrou as conquistas militares, as descobertas científicas e a literatura épica dos grandes reinos mesopotâmicos da Suméria, Assíria e Babilônia, e do poderoso Império Aquemênida da Pérsia, juntamente com preciosos detalhes da vida cotidiana no berço da civilização. E então… o significado dos caracteres se perdeu.

Por volta de 3.400 a.C. — enquanto os humanos se agrupavam em complexos assentamentos urbanos — um escriba na cidade-estado de Uruk, com suas muralhas de barro, pegou um estilete de junco para imprimir pequenos símbolos na argila. Por três milênios, a escrita cuneiforme (em forma de cunha) registrou as conquistas militares, as descobertas científicas e a literatura épica dos grandes reinos mesopotâmicos da Suméria, Assíria e Babilônia, e do poderoso Império Aquemênida da Pérsia, juntamente com preciosos detalhes da vida cotidiana no berço da civilização. E então… o significado dos caracteres se perdeu. London, 1857. In an era obsessed with human progress, mysterious palaces emerging from the desert sands had captured the Victorian public’s imagination. Yet Europe’s best philologists struggled to decipher the bizarre inscriptions excavators were digging up.

London, 1857. In an era obsessed with human progress, mysterious palaces emerging from the desert sands had captured the Victorian public’s imagination. Yet Europe’s best philologists struggled to decipher the bizarre inscriptions excavators were digging up.