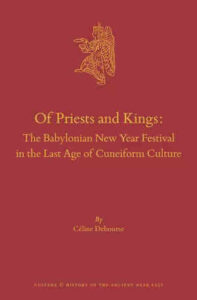

O capítulo 3 do livro Of Priests and Kings: The Babylonian New Year Festival in the Last Age of Cuneiform Culture, de Céline Debourse, trata das fontes textuais para o Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico, o Akitu, durante o Primeiro Milênio a.C. Transcrevo aqui alguns trechos.

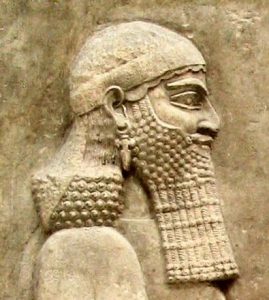

O período neoassírio

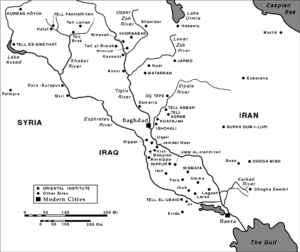

A primeira evidência que se relaciona diretamente com o Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico deriva, talvez surpreendentemente, de um contexto assírio. É em fontes assírias que encontramos pela primeira vez o rei levando Marduk pela mão para a procissão Akitu. No entanto, a maioria das fontes é sobre a tradição Akitu no próprio território assírio, cujo desenvolvimento ocorreu em grande escala e em alta velocidade. No entanto, mesmo que a maioria das fontes neoassírias relacione práticas assírias em vez de babilônicas, muitas vezes presume-se que os elementos mais importantes do festival foram emprestados da versão babilônica do Akitu. Em um sentido mais geral, a evidência neoassíria demonstra a importância do Akitu na sociedade babilônica já no oitavo século a.C.

que encontramos pela primeira vez o rei levando Marduk pela mão para a procissão Akitu. No entanto, a maioria das fontes é sobre a tradição Akitu no próprio território assírio, cujo desenvolvimento ocorreu em grande escala e em alta velocidade. No entanto, mesmo que a maioria das fontes neoassírias relacione práticas assírias em vez de babilônicas, muitas vezes presume-se que os elementos mais importantes do festival foram emprestados da versão babilônica do Akitu. Em um sentido mais geral, a evidência neoassíria demonstra a importância do Akitu na sociedade babilônica já no oitavo século a.C.

Resumo

As fontes neoassírias são as primeiras a lançar alguma luz sobre o Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico durante o primeiro milênio a.C. Elas mostram a importância do festival no mundo babilônico, não apenas pela disposição dos assírios em participar dele (no caso de Tiglat-Pileser III e Sargão II), mas também por sua ânsia em adotar o conceito e integrá-lo em sua própria ideologia. Além disso, a interrupção forçada do festival na Babilônia causada pela remoção de Marduk durante o reinado de Senaquerib também mostra o poder ideológico que o Akitu detinha na Babilônia. No entanto, as fontes assírias devem ser abordadas com muito cuidado quando se trata de reconstruir o festival babilônico. Embora esteja claro que os estudiosos assírios tomaram a tradição babilônica como modelo, eles a remodelaram para se adequar ao contexto assírio no qual foi inserida.

No entanto, algumas características gerais do Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico podem ser discernidas nesses textos, sem a necessidade de adaptá-los a partir de fontes posteriores. O material de origem neoassírio menciona apenas o festival Akitu da Babilônia e não registra nada sobre outras cidades babilônicas onde o festival pode ter ocorrido. Isso mostra como o festival nesta cidade era de particular importância. O fato de que os festivais Akitu eram observados em diferentes cidades assírias provavelmente também é modelado a partir de uma tradição babilônica existente.

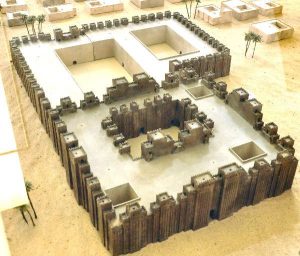

Também deve ser notado que já nessa época tanto Marduk quanto Nabú são os protagonistas divinos do festival na Babilônia. A importância de Nabú no Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico já estava estabelecida nessa época. Além disso, os registros deixam claro que a procissão dos deuses ao templo Akitu era a característica mais distintiva do Festival do Ano Novo: quase todas as fontes se concentram neste evento. Em relação ao Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico, o uso da frase “tomando Bel pela mão” é prevalente para se referir à procissão.

Por fim, não apenas o conteúdo das fontes, mas também sua natureza demonstra o lugar importante que o Festival do Ano Novo da Babilônia ocupava na sociedade e cultura babilônicas já no início do período sargônida. A escolha dos reis assírios para participar do festival babilônico é um dos indicadores disso, mostrando que eles usaram o Festival do Ano Novo como uma ferramenta para estabelecer pacificamente seu governo na Babilônia.

Não há dúvida de que havia uma forte tradição Akitu na Babilônia já no século VIII a.C., permitindo que os assírios a usassem dessa forma, mas os detalhes dela permanecem envoltos em escuridão. O festival acontecia anualmente? Os reis participavam? Quão importante era o festival para a legitimação real? Até que mais evidências venham à tona, essas questões devem permanecer sem resposta.

O período neobabilônico e o período persa inicial

Durante o período neobabilônico, o festival Akitu na Babilônia permaneceu como uma ferramenta para a legitimação real, como pode ser observado não apenas nas inscrições reais, mas também na tradição historiográfica emergente. Enquanto o festival na Babilônia era celebrado no Ano Novo e exaltava o rei, o deus nacional Marduk e o império babilônico, os documentos administrativos de outras cidades santuário mostram a observância de festivais Akitu locais em outros momentos do ano que giravam em torno da divindade padroeira local. Como tal, a continuidade — em termos gerais — com a tradição Akitu neoassíria pode ser observada independentemente das diferenças no material de origem. Em contraste, a mudança ocorreu de forma marcante com a chegada dos persas em 539 a.C. Esses novos governantes não parecem ter participado ou investido no festival. Apesar desse desinteresse real no Akitu, os registros administrativos mostram que os sacerdotes conseguiram manter alguns aspectos tradicionais do Festival do Ano Novo, como a jornada de Nabú de Borsipa para a Babilônia, mas somente até o reinado de Dario I.

Há cinco grupos de fontes que dão informações sobre o Festival do Ano Novo no longo século VI a.C.: inscrições reais, textos administrativos, crônicas, textos histórico-literários e composições de culto. Eles mostram como o Akitu era um fenômeno que não estava restrito aos templos, mas estava profundamente enraizado na cultura, na erudição e na ideologia real da Babilônia.

Resumo

O número de testemunhos em diferentes tipos de texto mostra como o Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico era parte integrante da vida religiosa, cultural e social da Babilônia durante o longo século VI a.C. Os textos se referem ao Akitu como um conceito tão bem definido na mentalidade babilônica que não precisa ser especificado por escrito e, portanto, as fontes não são muito indicativas para os detalhes da performance de culto, rituais e organização do festival. Em vez disso, a documentação neobabilônica pode ser melhor usada para estudar como o Festival era usado e percebido na sociedade babilônica.

Primeiro, na Babilônia, Akitu funciona praticamente como um sinônimo para “Festival de Ano Novo”. Em um significado secundário, a palavra se refere ao templo Akitu, embora nesses casos isso seja frequentemente especificado referindo-se ao edifício como bīt akīti. No contexto de outras cidades, Akitu perde sua conexão com o Ano Novo.

Segundo, a documentação é amplamente a favor do festival Akitu da Babilônia. Embora a administração dos templos locais forneça alguns vislumbres dos calendários de culto locais, incluindo um festival Akitu local, em inscrições públicas e círculos acadêmicos o conceito de Akitu estava inextricavelmente ligado à Babilônia. No entanto, o papel de Borsipa não deve ser negligenciado. A importância da cidade-irmã da Babilônia é refletida na parte proeminente atribuída a Marduk e Nabú no festival, outro elemento característico do Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico nessa época.

Terceiro, as fontes falam claramente que o Festival do Ano Novo estava associado ao rei e à realeza. Não é apenas um tópico recorrente nas inscrições reais, mas também está ligado à realeza nas Crônicas. Vários detalhes permanecem obscuros, no entanto. O silêncio das fontes em relação à participação anual do rei no festival pode ser considerado um argumento a favor dessa ideia? Qual período foi definidor para essa tradição de envolvimento real no Akitu e as Crônicas podem ser usadas como fontes confiáveis para responder a essa pergunta?

Quarto, as diferentes fontes estão quase todas preocupadas com o mesmo evento: procissões Akitu, seja a jornada de Nabú entre Borsipa e Babilônia ou as procissões de e para o templo Akitu. Claramente, esse era o aspecto mais importante do festival, o que pode ser explicado de muitas maneiras: pode ser o ato simbólico/ritual mais crucial; pode estar conectado à natureza perigosa de trazer os deuses para fora de seus templos, enfatizando assim a conclusão bem-sucedida desse esforço; ou pode ser simplesmente a natureza pública e festiva da procissão; e provavelmente foi a combinação de todos os elementos que fez disso o evento característico do Festival do Ano Novo.

Nabônides foi o último rei da Babilônia a mencionar o Akitu em suas inscrições. As Crônicas terminam, no máximo, com a chegada dos persas. E embora o material administrativo referente ao Akitu continue até o reinado do rei persa Dario I, é perceptível que a mudança havia se instalado de forma irreversível. Há um silêncio completo de 484 a.C. em diante e somente quando os Selêucidas estabeleceram firmemente seu reinado na Babilônia é que temos notícia novamente do Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico.

A Babilônia helenística

As ideias atuais sobre o Akitu também são baseadas em fontes que datam do período helenístico. Muitos estudiosos modernos subscrevem a ideia de que o Akitu continuou a ser realizado durante todo o período helenístico, seja como um renascimento de tradições antigas ou como uma continuidade ininterrupta do período neobabilônico até os períodos persa e helenístico. Além disso, é comumente assumido que o Akitu manteve seu formato de doze dias e incluiu a procissão dos deuses de e para o templo Akitu. Também é amplamente aceito que os reis Selêucidas participaram do festival da mesma forma que seus predecessores neobabilônicos.

No entanto, a natureza e o escopo do material de origem deste período são notavelmente diferentes dos de períodos anteriores. Nenhuma fonte emana do rei e, em vez disso, o material deriva de um contexto puramente sacerdotal. Além disso, novos gêneros são adotados e desenvolvidos, mais notavelmente os Diários Astronômicos e as Crônicas. Além disso, os diferentes tipos de fontes fornecem insights muito diferentes sobre o Akitu, em contraste com a documentação anterior, que coloca uma ênfase pesada na procissão e no papel do rei no festival.

No entanto, a natureza e o escopo do material de origem deste período são notavelmente diferentes dos de períodos anteriores. Nenhuma fonte emana do rei e, em vez disso, o material deriva de um contexto puramente sacerdotal. Além disso, novos gêneros são adotados e desenvolvidos, mais notavelmente os Diários Astronômicos e as Crônicas. Além disso, os diferentes tipos de fontes fornecem insights muito diferentes sobre o Akitu, em contraste com a documentação anterior, que coloca uma ênfase pesada na procissão e no papel do rei no festival.

Resumo

Em resumo, a documentação referente ao Akitu babilônico no período helenístico difere muito daquela de períodos anteriores, tanto no tipo de fontes disponíveis quanto no que elas relatam. A questão é se isso se deve a meras mudanças documentais ou a diferenças reais no culto. Por exemplo: não é nenhuma surpresa que não haja fontes helenísticas que derivem do rei, como foi o caso nos períodos neoassírio e neobabilônico, porque não havia mais um rei nativo da Babilônia.

Um aspecto notável é a discrepância entre registros contemporâneos e aquelas fontes que relatam eventos do passado. Atente-se para o fato de que nenhuma das fontes contemporâneas atesta a procissão Akitu com exceção de um documento do período parta que o faz parecer um evento bastante pequeno e banal. O que é relatado nesses textos é principalmente limitado a oferendas e outras atividades rituais que ocorreram no Eságil e dentro do é.ud.1kam. Em contraste, a procissão ainda é o tópico central nos relatos Akitu nas Crônicas históricas, que também são as únicas fontes que se referem ao evento com terminologia conhecida da documentação pré-persa.

Também a função atribuída ao rei é diferente na documentação contemporânea, por um lado, e nos relatos históricos, por outro. Enquanto o rei é apresentado como a força motriz por trás dos festivais Akitu do passado, na Babilônia helenística ele parece desempenhar um papel bastante distante e passivo, deixando a iniciativa com o sacerdócio local. Especificamente, isso também distingue as Crônicas históricas de textos anteriores, pois elas apresentam o sumo sacerdote como um agente proeminente no festival. À luz disso, é notável que alguns dos textos rituais incluam o rei como um participante do Festival. Isso levanta a questão da função desses textos em um contexto no qual o governante estava ausente.

Considerações finais e perspectiva

A pesquisa de fontes deixa claro que não podemos manter nossas ideias convencionais sobre a continuidade do Akitu e nem podemos falar de algo como “o” Akitu. Em nenhum momento no tempo podemos reconstruir a estrutura básica e os princípios do festival celebrado na Babilônia no Ano Novo com base apenas em fontes contemporâneas. Além disso, uma série de diferenças são discerníveis no material disponível, não apenas entre as fontes neoassírias e neobabilônicas, mas ainda mais fortes entre o material neobabilônico e o babilônico tardio. Claramente, o Akitu mudou ao longo do tempo e foi fortemente influenciado por seu contexto histórico, apesar da natureza inerentemente conservadora do ritual.

Uma coisa é inegavelmente verdadeira: o Akitu ou Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico foi uma parte integral e constante da cultura cuneiforme durante todo o primeiro milênio a.C., como pode ser verificado em textos cuneiformes que datam do período neoassírio ao parta. Não apenas muitas fontes atestam a observação cultual do Ano Novo e a realização do festival Akitu, tanto na Assíria quanto na Babilônia, mas o Akitu também se tornou parte da memória cultural dessas sociedades. Em contraste, a apresentação real assumiu formas distintas em diferentes cenários, embora muitas vezes não se possa dizer muito sobre o que exatamente aconteceu. Portanto, deve-se distinguir entre uma noção abstrata do Festival do Ano Novo e o festival que foi realmente realizado. De certa forma, os antigos mesopotâmicos fizeram o mesmo, como fica claro na adoção do festival pelos sargônidas. Isso se torna especialmente visível nas fontes do período helenístico, quando há uma clara discrepância entre o que aprendemos sobre o Ano Novo a partir de fontes contemporâneas, por um lado, e de composições cultuais e historiográficas, por outro.

As semelhanças entre o material neoassírio e neobabilônico são múltiplas. Muitas das fontes emanam do rei (ou pelo menos do círculo de estudiosos ao seu redor) e também aquelas poucas que derivam de um contexto diferente mostram o envolvimento do rei no festival. Além disso, é claro que se deve distinguir entre o festival Akitu da capital e aqueles de outras cidades. Enquanto o último serviu a um propósito local de elevar o deus principal do panteão local, o primeiro tinha um objetivo nacional: celebrar o chefe do panteão nacional, marcar o Ano Novo e reafirmar o rei como governante do império. Dentro dessa imagem, o foco permaneceu na Babilônia, a sede final do festival Akitu e da realeza mesopotâmica. Enquanto as evidências antes dessa época são pequenas (para dizer o mínimo), é inegável que a partir dos sargônidas o festival Akitu se tornou um fator crucial na ideologia real. Isso continuou sob os reis neobabilônicos. Isso explica a alta concentração de referências à procissão: esse era o momento em que todos podiam ver o vínculo entre o deus e o rei sendo restabelecido. Não havia prova mais forte da legitimidade de um rei do que essa.

Enquanto durante a primeira metade do primeiro milênio a.C. a ideia do Akitu, por um lado, e sua performance real, por outro, parecem ter permanecido bem próximas uma da outra, elas parecem ser duas coisas distintas no período helenístico. O dado seguinte pode ilustrar isso: um dos principais propósitos do festival era apresentar o rei como um governante aprovado pelos deuses; portanto, os reis participavam dele, patrocinavam e garantiam que ele pudesse ser celebrado – tudo isso pode ser lido nas fontes neoassírias e neobabilônicas. No entanto, nas fontes helenísticas, os textos contemporâneos raramente mencionam o envolvimento real, enquanto o discurso acadêmico e cultual continuou a apresentar o Akitu como um festival para legitimação real. Como tal, há uma sensação de incongruência no material de origem helenística que não encontramos nos textos anteriores.

Como foi mostrado neste capítulo, um grande número de fontes está disponível para estudar o Festival do Ano Novo Babilônico ao longo do primeiro milênio a.C. No entanto, um grupo de textos é de extrema importância para nossa compreensão do festival, uma vez que eles dão um relato detalhado dos eventos que aconteciam antes da procissão dos deuses. Esses textos rituais são geralmente considerados como tendo se originado na primeira metade do primeiro milênio a.C., embora todos os manuscritos conhecidos datem do período helenístico. Supõe-se que eles foram usados no culto e que os rituais que eles contêm foram realizados exatamente como é descrito. O problema é que os textos do Festival do Ano Novo, como costumamos chamar os textos deste corpus, nunca foram submetidos a um exame minucioso, o que significa que falhamos em compreender sua função e permanecemos no escuro sobre seu contexto de criação. Nos capítulos seguintes, os textos do Festival do Ano Novo da Babilônia serão estudados extensivamente, a fim de entender melhor seu propósito, contexto de criação e relação com outras fontes para o Akitu no primeiro milênio a.C.

Fontes online:

1. Oracc – The Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus

2. As inscrições reais do período neoassírio – Post publicado no Observatório Bíblico em 07.04.2020

The Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period (RINAP)

3. Inscrições reais de Babilônia – Post publicado no Observatório Bíblico em 20.12.2017

The Royal Inscriptions of Babylonia online (RIBo) Project

Chapter 3

Textual Sources for the Babylonian New Year Festival During the First Millennium BCE

In this chapter, I will re-evaluate the sources that are commonly used to study the NYF celebrated at Babylon in the first millennium BCE.

3.1 The Neo-Assyrian Period

The first evidence that directly relates to the Babylonian NYF stems, perhaps surprisingly, from an Assyrian context. It is in Assyrian sources that we first encounter the king taking Marduk by the hand for the akītu-procession. Nevertheless, the majority of the sources are about the akītu-tradition in the Assyrian heartland itself, the development of which took place on a grand scale and at high speed. Yet, even if most NA sources relate Assyrian practices rather than Babylonian, it is often presumed that the most important elements in the festival were borrowed from the Babylonian version of the akītu. In a more general sense, the Neo-Assyrian evidence demonstrates the importance of the NYF in Babylonian society already in the eighth century BCE.

3.1.4 Summary

The Neo-Assyrian sources are the first to shed some light on the Babylonian NYF during the first millennium BCE. They show the importance of the festival in the Babylonian world, not only through the Assyrians’ willingness to participate in it (in the case of Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon), but also because of their eagerness to adopt the concept and integrate it into their own ideology. Moreover, the forced disruption of the festival in Babylon caused by the removal of Marduk also shows the ideological power the NYF held in Babylonia. The Assyrian sources should be approached very carefully when it comes to reconstructing the Babylonian festival, however. Even though it is clear that Assyrian scholars took the Babylonian tradition as a model, they reshaped it to fit the Assyrian context into which it was inserted.

Babylonian world, not only through the Assyrians’ willingness to participate in it (in the case of Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon), but also because of their eagerness to adopt the concept and integrate it into their own ideology. Moreover, the forced disruption of the festival in Babylon caused by the removal of Marduk also shows the ideological power the NYF held in Babylonia. The Assyrian sources should be approached very carefully when it comes to reconstructing the Babylonian festival, however. Even though it is clear that Assyrian scholars took the Babylonian tradition as a model, they reshaped it to fit the Assyrian context into which it was inserted.

Nevertheless, a few general characteristics of the Babylonian NYF can be discerned in these texts, without needing to retrofit them from later sources. The Neo-Assyrian source material mentions only the akītu-festival of Babylon and does not record anything about other Babylonian cities where the festival might have taken place. This shows how the festival in this city was of particular importance. The fact that akītu-festivals were observed in different Assyrian cities is probably also modeled after an existing Babylonian tradition. It should also be noted that already at this time both Marduk and Nabû are the divine protagonists of the festival at Babylon. The importance of Nabû in the Babylonian NYF was thus already established at this time. Aside from that, the records make clear that the procession of gods to the akītu-temple was the most distinctive characteristic of the NYF: almost all the sources focus on this event. In relation to the Babylonian NYF, the use of the phrase “taking Bēl by the hand” is prevalent to refer to the procession. Lastly, not only the content of the sources, but also their nature demonstrates the important place the NYF of Babylon held in Babylonian society and culture already at the onset of the Sargonid period. The choice of Assyrian kings to participate in the Babylonian festival is one of the indicators of this, showing that they used the NYF as a tool to peacefully establish their rule in Babylonia. There is no doubt that there was a strong akītu-tradition in Babylon already in the eighth century BCE, allowing the Assyrians to use it in that way, but the details of it remain shrouded in darkness. Did the festival happen on a yearly basis? Did kings participate? How important was the festival for royal legitimation? Until more evidence comes to light, those questions must remain unanswered.

3.2 The Neo-Babylonian and Early Persian Period

During the Neo-Babylonian period the akītu-festival at Babylon remained a tool for royal legitimation as can be observed not only in the royal inscriptions, but also in the emergent historiographical tradition. While the festival at Babylon was celebrated at the New Year and exalted the king, the national god Marduk and the Babylonian empire, the administrative documents of other temple cities show the observance of local akītu-festivals at other moments in the year that revolved around the local patron deity. As such, continuity—in broad terms—with the Neo-Assyrian akītu-tradition can be observed regardless of the differences in the source material. In contrast, change markedly set in with the arrival of the Persians in 539 BCE. These new rulers do not seem to have participated or invested in the festival. Despite this royal disinterest in the NYF, the administrative records show that the priesthoods managed to uphold some traditional aspects of the NYF, such as the journey of Nabû from Borsippa to Babylon, but only until the reign of Darius I.

There are five groups of sources that give information about the NYF in the Long Sixth Century: royal inscriptions, administrative texts, chronicles, historical-literary texts, and cultic compositions. They show how the NYF was a phenomenon that was not restricted to the temples but was deeply embedded in Babylonian culture, scholarship and royal ideology.

Summary

The number of attestations in different text types shows how the Babylonian NYF was an integral part of Babylonian religious, cultural, and social life during the Long Sixth Century. The texts refer to the NYF as a concept so well defined in Babylonian mentality that it need not be specified in writing and, thus, the sources are not very indicative for the details of the cultic performance, rituals, and organization of the festival. Instead, the Neo-Babylonian documentation can best be used to study how the NYF was used and perceived in Babylonian society.

First, in Babylon akītu functions practically as a synonym for “New Year Festival” and it often occurs together with zagmukku and rēš šatti. In a secondary meaning, the word refers to the akītu-temple, although in those cases this is often specified by referring to the building as the bīt akīti. In the context of other cities, akītu loses its connection to the New Year.

Second, the documentation is largely in favor of the akītu-festival of Babylon. Although the local temples’ administration provides some glimpses into local cultic calendars, including a local akītu-festival, in public inscriptions and scholarly circles the concept of akītu was inextricably linked to Babylon. However, the role of Borsippa should not be neglected. The importance of Babylon’s sister-city is reflected in the prominent part assigned to both Marduk and Nabû in the festival, another characteristic element of the Babylonian NYF at this time.

Third, it speaks clearly from the sources that the NYF was associated with the king and kingship. Not only is it a recurrent topic in royal inscriptions, it is also linked with kingship in the chronicles. Several details remain unclear, however. Can the silence of the sources regarding the yearly participation of the king in the festival be considered an argument in favor of that idea? Which period was defining for this tradition of royal involvement in the NYF and can the chronicles be used as reliable sources to answer that question?

Fourth, the different sources are almost all concerned with the same event: the akītu-processions, be it the journey of Nabû between Borsippa and Babylon or the processions to and from the akītu-temple. Clearly this was the most important aspect of the festival, which can be explained in many ways: it may be the most crucial symbolic/ritual act; it may be connected to the dangerous nature of bringing the gods out of their temples, thus emphasizing the successful completion of that endeavor; or it may simply be the procession’s public and festive nature; and probably it was the combination of all elements that made this into the characteristic event of the NYF.

Nabonidus was the last king in Babylon to mention the akītu-festival in his inscriptions; the chronicles end, at the latest, with the arrival of the Persians; and although the administrative material regarding the NYF continues until the reign of the Persian king Darius I, it is noticeable that change had irreversibly set in. A complete silence descends from about 484 BCE onwards and not until the Seleucids had firmly established their reign in Babylonia do we learn again about the Babylonian NYF.

3.3 Hellenistic Babylon

Current ideas about the Babylonian NYF are also based on sources dating to the Hellenistic period. Many modern scholars subscribe to the idea that the NYF continued to be performed throughout the Hellenistic period, whether as a revival of ancient traditions or as an uninterrupted continuity from the Neo-Babylonian through the Persian and Hellenistic periods. Furthermore, it is commonly assumed that the NYF retained its twelve-day format and included the procession of gods to and from the akītu-temple. It is also widely accepted that Seleucid kings participated in the festival in the same vain as their Neo-Babylonian predecessors.

However, the nature and scope of the source material from this period is remarkably different from that of earlier periods. No sources emanate from the king and instead the material stems from a purely priestly context. Moreover, new genres are adopted and developed, most conspicuously the Astronomical Diaries and Chronicles. Aside from that, the different types of sources provide very different insights into the NYF, in contrast to the earlier documentation, which places a heavy emphasis on the procession and the role of the king in the festival.

However, the nature and scope of the source material from this period is remarkably different from that of earlier periods. No sources emanate from the king and instead the material stems from a purely priestly context. Moreover, new genres are adopted and developed, most conspicuously the Astronomical Diaries and Chronicles. Aside from that, the different types of sources provide very different insights into the NYF, in contrast to the earlier documentation, which places a heavy emphasis on the procession and the role of the king in the festival.

In the following, an overview is given of the sources that are generally used to prove the undisturbed continuity of the Babylonian NYF and the king’s participation in it. The focus will lie on a critical re-evaluation of this evidence, in order better to assess the question of continuity and change.

3.3.4 Summary

In summary, the documentation regarding the Babylonian NYF in the Hellenistic period differs greatly from that of earlier periods, both in the kind of sources available and in what they recount. The question is whether this is due to mere documentary changes or to actual differences in the cult. For example: it comes as no surprise that there are no Hellenistic sources that derive from the king, as was the case in the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods, because there was no longer a native Babylonian king.

A remarkable aspect is the discrepancy between contemporary records and those sources that relate events from the past. A case was made for the fact that none of the contemporaneous sources attests the akītu-procession, with the exception of one Parthian-period document that makes it seem like a rather small and unremarkable event. What is related in these texts is mostly limited to offerings and other ritual activities that took place at Esagil and inside the é.ud.1kam. In contrast, the procession is still the central topic in the akītu-accounts in the historical chronicles, which are also the only sources to refer to the event with terminology known from the pre-Persian documentation.

Also the function ascribed to the king is different in the contemporary documentation on the one hand and historical accounts on the other. Whereas the king is presented as the driving force behind the akītu-festivals of the past, in Hellenistic Babylon he appears to play a rather distant and passive role, leaving the initiative with the local priesthood. Specifically, this also distinguishes the historical chronicles from earlier texts, as they do present the high priest as a prominent agent in the festival. In light of this, it is remarkable that some of the ritual texts include the king as a participant in the NYF. This raises the question of the function of those texts in a context in which the ruler was mostly absent.

3.4 Summary and Outlook

The survey of sources above makes it clear that we cannot maintain our long-standing ideas about the continuity of the Babylonian NYF nor can we speak of such a thing as “the” NYF. For no moment in time can we reconstruct the basic structure and principles of the festival celebrated in Babylon at the New Year based on contemporary sources alone. Furthermore, a number of differences are discernible in the available material, not only between the Neo-Assyrian and the Neo-Babylonian sources, but even stronger between the Neo-Babylonian and the Late Babylonian material. Clearly, the Babylonian NYF changed over time and was heavily influenced by its historical context, despite the inherently conservative nature of ritual.

One thing is undeniably true: the Babylonian akītu or NYF was an integral and constant part of cuneiform culture during the whole first millennium BCE, as it can be found in cuneiform texts dating from the Neo-Assyrian to the Parthian periods. Not only do many sources attest to the cultic observation of the New Year and the performance of the akītu-festival, in both Assyria and Babylonia, but akītu also became part of the cultural memory of those societies. In contrast, the actual performance took distinct forms in different settings, although often not much can be said about what exactly happened. Therefore, one should distinguish between an abstract notion of the NYF and the festival that was actually performed. In a way, the ancient Mesopotamians did the same, as is clear in the adoption of the festival by the Sargonids. It especially becomes visible in the sources from the Hellenistic period, when there is a clear discrepancy between what we learn about the New Year from contemporary sources on the one hand and from cultic and historiographical compositions on the other.

The similarities between the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian material are manifold. Many of the sources emanate from the king (or at least the circle of scholars around him) and also those few that do stem from a different context show the involvement of the king in the festival. Aside from that, it is clear that one should distinguish between the akītu-festival of the capital and those of other cities. While the latter served a local purpose of elevating the main god of the local pantheon, the former had a state-wide aim: to celebrate the head of the national pantheon, to mark the New Year, and to reaffirm the king as ruler of the empire. Within that picture, the focus remained on Babylon, the ultimate seat of the akītu-festival and Mesopotamian kingship. Whereas evidence before this time is slight (to say the least), it is undeniable that from the Sargonids onwards the akītu-festival became a crucial factor in the royal ideology. This continued under the Neo-Babylonian kings. It explains the high concentration of references to the procession: this was the moment when everyone could see the bond between god and king being re-established. There was no stronger proof of a king’s legitimacy than that.

While during the first half of the first millennium BCE the idea of the NYF on the one hand and its actual performance on the other seem to have remained quite close to each other, they seem to be two separate things in the Hellenistic period. The following can illustrate that: one of the main purposes of the festival was to present the king as a ruler of whom the gods approved; therefore, kings participated in it, sponsored it and made sure that it could be celebrated—all of that can be read in the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian sources. However, in the Hellenistic sources, the contemporary texts only rarely mention royal involvement, while the scholarly and cultic discourse continued to present the NYF as a festival for royal legitimation. As such, there is a sense of incongruity in the Hellenistic source material that we do not find in the earlier texts.

each other, they seem to be two separate things in the Hellenistic period. The following can illustrate that: one of the main purposes of the festival was to present the king as a ruler of whom the gods approved; therefore, kings participated in it, sponsored it and made sure that it could be celebrated—all of that can be read in the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian sources. However, in the Hellenistic sources, the contemporary texts only rarely mention royal involvement, while the scholarly and cultic discourse continued to present the NYF as a festival for royal legitimation. As such, there is a sense of incongruity in the Hellenistic source material that we do not find in the earlier texts.

As was shown in this chapter, a large number of sources are available to study the Babylonian NYF throughout the first millennium BCE. Nevertheless, one group of texts is of extreme importance for our understanding of the festival, since they give a detailed account of the events that happened before the procession of gods took place. These ritual texts are generally considered to have originated in the first half of the first millennium BCE, although all the known manuscripts date to the Hellenistic period. It is assumed that they were used in the cult and that the rituals they contain were performed exactly as is described. The problem is that the NYF texts, as we can call the texts of this corpus, have never been subjected to close scrutiny, which means that we fail to grasp their function and remain in the dark about their context of creation. In the following chapters, the NYF texts from Babylon will be studied extensively, in order better to understand their purpose, context of creation, and relation to other sources for the Babylonian NYF in the first millennium BCE.