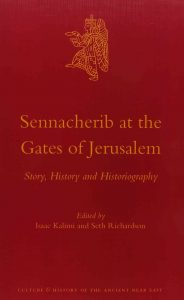

Estou lendo trechos do livro de KALIMI, I. ; RICHARDSON, S. (eds.) Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill, 2014, XII + 548 p. – ISBN 9789004265615.

Resumi os pontos principais do capítulo 4 sobre a tomada de Laquis.

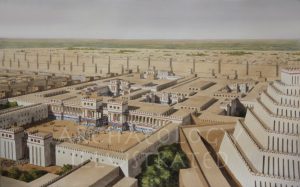

1. Laquis na época da campanha de Senaquerib

3. Os relevos de Laquis

Nas páginas 79-85, diz David Ussishkin:

O ataque assírio a Laquis

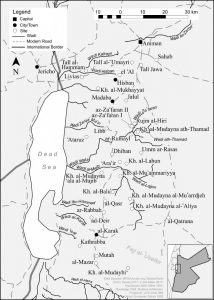

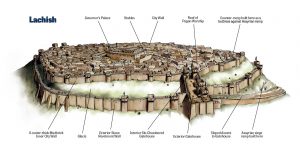

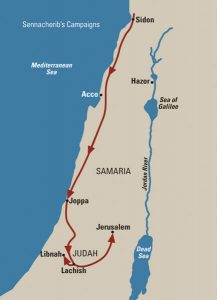

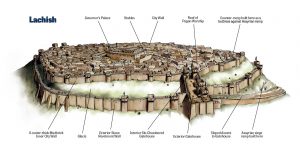

Quando Senaquerib chegou a Laquis no comando de seu exército, ele não teve que deliberar muito sobre onde dirigir o seu ataque à cidade fortificada. A resposta óbvia foi ditada pela topografia do local e pelo terreno circundante. A cidade estava cercada por vales profundos de quase todos os lados, e somente no ângulo sudoeste havia uma ligação, através de uma depressão, com a colina vizinha. As fortificações neste lado eram especialmente reforçadas, mas o ângulo sudoeste e a porta da cidade, que ficava nas vizinhanças, eram os pontos mais vulneráveis e lógicos a serem atacados. Por isso, é bastante natural que o lado sudoeste tenha sofrido o impacto do ataque assírio.

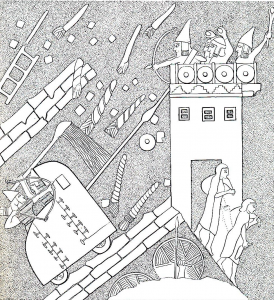

Ao chegar a Laquis, o exército deve ter acampado, como era usual nas campanhas assírias. Deve ter sido um acampamento espaçoso, fornecendo instalações para a força expedicionária e acomodando o séquito e o quartel-general do rei. Os acampamentos militares assírios são frequentemente retratados em relevos. Eles eram geralmente redondos ou elípticos e cercados por uma paliçada ou por um muro. O acampamento construído em Laquis é retratado de maneira semelhante nos “Relevos de Laquis”, uma série de gravuras retratando o evento da tomada da cidade, descobertas no palácio de Senaquerib em Nínive.

Parece que o local do acampamento assírio pode ser determinado com certa segurança. Considerações estratégicas sugerem (a) que o acampamento assírio deveria estar localizado não muito longe do local onde seria lançado o principal ataque às muralhas da cidade; (b) que deveria estar perto da cidade, mas fora do alcance das chamas das muralhas da cidade; (c) que não deveria ter sido topograficamente inferior ou dominado taticamente pelas muralhas da cidade; e (d) que o local do acampamento deveria ser relativamente plano e espaçoso, suficientemente grande para acomodar a força expedicionária e o quartel-general do rei. Os critérios acima se encaixam na colina a sudoeste do monte, onde agora está o povoado israelense de Moshav Lachish. Como esta colina está conectada ao monte por uma depressão, a abordagem à cidade foi bastante fácil, e o acampamento estava localizado em frente ao local onde o ataque principal deveria ocorrer. Esta colina é relativamente alta e seu cume é amplo e plano, sendo quase tão alto quanto as muralhas da cidade do lado sudoeste. Infelizmente, a reconstrução do acampamento assírio neste local não pode ser fundamentada arqueologicamente. Quaisquer restos desse acampamento, se ainda preservados, agora estão sob as casas e fazendas de Moshav Lachish.

Parece que o local do acampamento assírio pode ser determinado com certa segurança. Considerações estratégicas sugerem (a) que o acampamento assírio deveria estar localizado não muito longe do local onde seria lançado o principal ataque às muralhas da cidade; (b) que deveria estar perto da cidade, mas fora do alcance das chamas das muralhas da cidade; (c) que não deveria ter sido topograficamente inferior ou dominado taticamente pelas muralhas da cidade; e (d) que o local do acampamento deveria ser relativamente plano e espaçoso, suficientemente grande para acomodar a força expedicionária e o quartel-general do rei. Os critérios acima se encaixam na colina a sudoeste do monte, onde agora está o povoado israelense de Moshav Lachish. Como esta colina está conectada ao monte por uma depressão, a abordagem à cidade foi bastante fácil, e o acampamento estava localizado em frente ao local onde o ataque principal deveria ocorrer. Esta colina é relativamente alta e seu cume é amplo e plano, sendo quase tão alto quanto as muralhas da cidade do lado sudoeste. Infelizmente, a reconstrução do acampamento assírio neste local não pode ser fundamentada arqueologicamente. Quaisquer restos desse acampamento, se ainda preservados, agora estão sob as casas e fazendas de Moshav Lachish.

As escavações neste lado sudoeste foram iniciadas em 1932, quando Starkey descobriu e limpou o revestimento externo ao redor de todo o monte. Grandes quantidades de pedras foram descobertas neste local, e as escavações se estenderam pela encosta à medida que mais pedras foram removidas. A área da depressão no sopé do canto sudoeste e a estrada que levava à porta da cidade foram desobstruídas de muitos milhares de toneladas de alvenaria caída. Starkey acreditava que essas pedras caíram de cima, das muralhas destruídas durante o ataque assírio. David Ussishkin retomou a escavação deste lado sudoeste em 1983. Logo se tornou evidente que as pedras encontradas por Starkey estavam irregularmente amontoadas na encosta do monte, em vez de caírem de cima, e, portanto, ficou claro que elas formam os restos da rampa do cerco assírio. Estas escavações possibilitaram, em boa medida, a reconstrução do ataque assírio. Embora parcialmente removida por Starkey, a rampa de cerco colocada no fundo da encosta ainda podia ser estudada e reconstruída. Na sua parte inferior a rampa de cerco inclinada deve ter cerca de 70 metros de largura e 50 metros de comprimento. O centro da rampa de cerco era feito inteiramente de grandes pedras amontoadas que devem ter sido coletadas nos campos ao redor. Calcula-se que o total das pedras empregadas na construção da rampa devessem pesar de 13 a 19 mil toneladas.

As pedras da camada superior da rampa de cerco estavam ligadas por dura argamassa. Essa camada era a cobertura da rampa, adicionada por cima das pedras soltas, a fim de criar uma superfície compacta que permitisse aos soldados atacantes e suas máquinas de cerco se movimentarem em terreno sólido. O topo da rampa de cerco ao pé da muralha da cidade era coroado por uma plataforma horizontal feita de terra vermelha e suficientemente larga, fornecendo terreno uniforme para as máquinas de cerco assírias. É preciso enfatizar que a rampa de cerco de Laquis é, primeiro, a mais antiga rampa de cerco descoberta até hoje em escavações arqueológicas e, segundo, a única rampa de cerco assíria até agora conhecida.

fim de criar uma superfície compacta que permitisse aos soldados atacantes e suas máquinas de cerco se movimentarem em terreno sólido. O topo da rampa de cerco ao pé da muralha da cidade era coroado por uma plataforma horizontal feita de terra vermelha e suficientemente larga, fornecendo terreno uniforme para as máquinas de cerco assírias. É preciso enfatizar que a rampa de cerco de Laquis é, primeiro, a mais antiga rampa de cerco descoberta até hoje em escavações arqueológicas e, segundo, a única rampa de cerco assíria até agora conhecida.

Acima da rampa de cerco foram descobertas as fortificações do lado sudoeste, que eram especialmente maciças e fortes neste ponto vulnerável. A muralha externa tinha aqui uma torre construída com tijolos de barro sobre fundações de pedra, com cerca de 6 metros de altura, preservada quase em sua altura original. A torre era encimada por um balcão protegido por um parapeito, sobre o qual os defensores podiam ficar de pé e lutar. A principal muralha da cidade se estendia atrás e acima dessa torre. Foi preservada nesse ponto quase em sua altura original, cerca de 5 metros.

Quando os defensores da cidade viram que os assírios estavam construindo uma rampa de cerco como preparação para tomar as muralhas da cidade, começaram a construir uma contrarrampa dentro da muralha principal da cidade. Despejaram ali grandes quantidades de detritos do monte, retirados dos níveis anteriores da cidade, que trouxeram da parte nordeste, e construíram uma grande rampa, mais alta que a muralha principal da cidade, o que lhes proporcionou uma segunda nova linha interna de defesa.

Como resultado da construção da contrarrampa, o canto sudoeste tornou-se a parte mais alta do monte. A contrarrampa, sem dúvida, era uma muralha muito impressionante, seu ápice subindo cerca de 3 metros acima do topo da principal muralha da cidade. Alguma cerca ou muro improvisado, talvez feito de madeira, deve ter coroado a muralha, mas seus restos não foram preservados. As sondagens no centro da contrarrampa revelaram acúmulo de detritos montanhosos contendo cerâmica muito anterior, bem como lascas de calcário, que foram despejadas em camadas diagonais. Quando os assírios alcançaram os muros e superaram a defesa, estenderam a rampa de cerco sobre a muralha da cidade em ruínas para permitir o ataque à recém-formada linha de defesa mais alta da contrarrampa.

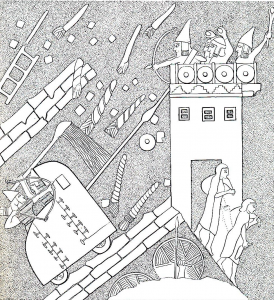

Falando das armas e munições usadas na batalha, vale mencionar primeiro a máquina de cerco, a formidável arma usada pelos assírios para destruir a linha de defesa nas muralhas. Nada menos do que sete máquinas de cerco dispostas para a batalha no topo da rampa de cerco e perto da porta da cidade são retratadas nos relevos de Laquis. O aríete era feito de uma viga de madeira reforçada com uma ponta afiada de metal. Como demonstrado no relevo, os defensores judaítas de pé na muralha lançavam tochas flamejantes nas máquinas de cerco. Como contramedida, os soldados assírios despejavam água de longas conchas nas máquinas para impedir que pegassem fogo, pois eram feitas de madeira e couro.

Mais duas descobertas únicas estão associadas às tentativas dos defensores de destruir as máquinas de cerco. O primeiro inclui doze pedras perfuradas que foram descobertas ao pé das duas muralhas da cidade. São grandes blocos de pedra perfurada, com uma parte superior plana, lados retos e um fundo irregular. Cada um deles tem quase 60 cm de diâmetro e pesa cerca de 100 a 200 kg. Restos de cordas queimadas e relativamente finas foram encontrados nos buracos de duas pedras.

descobertas ao pé das duas muralhas da cidade. São grandes blocos de pedra perfurada, com uma parte superior plana, lados retos e um fundo irregular. Cada um deles tem quase 60 cm de diâmetro e pesa cerca de 100 a 200 kg. Restos de cordas queimadas e relativamente finas foram encontrados nos buracos de duas pedras.

Conforme indicado pelos restos das cordas, parece que as pedras perfuradas foram amarradas e baixadas pelos defensores da muralha da cidade. Pode-se supor que essas pedras tenham sido baixadas de alguma instalação improvisada, como uma grossa viga de madeira que se projetava da linha da muralha. Os defensores provavelmente usaram as pedras na tentativa de danificar as máquinas de cerco e impedir que os aríetes batessem na muralha. Eles devem ter descido as pedras sobre as máquinas de cerco e as movido de um lado para o outro como um pêndulo.

A segunda descoberta é um fragmento de uma corrente de ferro contendo quatro elos longos e estreitos, que foram descobertos nos restos de tijolos de barro queimados em frente ao revestimento externo. Os defensores provavelmente usaram a corrente de ferro para desequilibrar as máquinas de cerco. Devem ter lançado a corrente abaixo do ponto de impulso do aríete para prender seu eixo quando atingiu a muralha e depois puxaram a corrente.

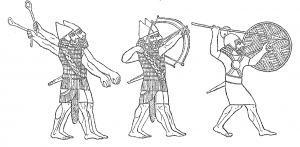

Algumas das munições usadas na batalha também foram encontradas. Os relevos de Laquis exibem soldados assírios com fundas atirando nos defensores das muralhas, bem como defensores judaítas atirando pedras contra os atacantes, e muitas pedras atiradas foram de fato encontradas nas escavações. São bolas de sílex ou calcário bem moldadas, semelhantes a bolas de tênis, e pesando cerca de 250 gramas ou mais.

Os relevos de Laquis exibem arqueiros assírios que apoiavam o ataque às muralhas e, de fato, cerca de mil pontas de flechas foram descobertas nas escavações no canto sudoeste. As pontas de flechas não são uniformes em tamanho ou forma, e são de tipos diferentes. Quase todos eram feitas de ferro, e algumas eram de bronze ou esculpidas em osso. A maioria das pontas de flecha foi descoberta nos destroços de tijolos de barro queimados em frente às muralhas da cidade. Aparentemente, essas flechas foram disparadas por arqueiros assírios contra os soldados judaítas que estavam nos balcões no topo das muralhas. A descoberta de tantas pontas de flecha em uma área tão pequena indica a concentração do poder de fogo assírio. Muitas pontas de flecha foram encontradas dobradas, uma indicação de que foram atiradas muito de perto contra as muralhas com arcos poderosos.

Infelizmente, os dados arqueológicos são insuficientes para responder a três perguntas básicas:

. Qual era o tamanho da população da cidade na época do cerco?

. Qual era o tamanho da força assíria?

. Quanto tempo durou o cerco?

Em relação ao número de habitantes e defensores, só podemos fazer uma estimativa aproximada. O método costumeiro para calcular o tamanho da população em um assentamento antigo é multiplicando a área estabelecida por um coeficiente de densidade. Adotando o coeficiente de 100 pessoas por acre, já usado por especialistas para esta época, conclui-se que pelo menos duas mil pessoas viviam em Laquis na época da invasão de Senaquerib. No entanto, esse método serve para calcular a população em um assentamento regular, enquanto Laquis era principalmente um centro militar fortificado. Além disso, é possível que o número de pessoas em Laquis tenha mudado às vésperas do cerco, seja porque as pessoas da região circundante se refugiaram ali ou devido a mudanças que foram feitas no destacamento do exército judaíta.

assentamento antigo é multiplicando a área estabelecida por um coeficiente de densidade. Adotando o coeficiente de 100 pessoas por acre, já usado por especialistas para esta época, conclui-se que pelo menos duas mil pessoas viviam em Laquis na época da invasão de Senaquerib. No entanto, esse método serve para calcular a população em um assentamento regular, enquanto Laquis era principalmente um centro militar fortificado. Além disso, é possível que o número de pessoas em Laquis tenha mudado às vésperas do cerco, seja porque as pessoas da região circundante se refugiaram ali ou devido a mudanças que foram feitas no destacamento do exército judaíta.

Quanto ao tamanho do exército assírio acampado em Laquis, ou ao tamanho da força que participou do ataque à cidade, não há dados disponíveis. Quanto à questão de quanto tempo durou o cerco da cidade, aparentemente foi um cerco breve, pois toda a campanha assíria durou apenas parte de um ano. Durante esse período, o exército assírio marchou da Assíria para Judá, subjugou a Fenícia e a Filisteia, lutou contra a força expedicionária egípcia, conquistou parte de Judá e voltou para casa. Parece que a maior parte do tempo necessário para o ataque a Laquis foi gasto na construção da rampa de cerco, enquanto o ataque às muralhas da cidade foi relativamente breve. Ephʿal tentou calcular o tempo necessário para a instalação da rampa de assédio e sugeriu que tenha demorado vinte e poucos dias. No entanto, todos os dados básicos necessários para os cálculos, como a quantidade de pedras despejadas na rampa de cerco, a distância de onde foram levadas, o número de carregadores empregados para transportá-las e os atrasos causados pela oposição dos defensores, só podem ser supostos.

The Assyrian Attack on Lachish

When Sennacherib arrived at the head of his army at Lachish, he did not have to deliberate at length on where to direct the main thrust of his onslaught on the fortified city. The obvious answer was dictated by the topography of the site and the surrounding terrain. The city was enveloped by deep valleys on nearly all sides, and only at the southwest corner did a topographical saddle connect the mound with the neighboring hillock. The fortifications at this corner were specially strengthened, but nevertheless the southwest corner and the nearby city-gate were the most vulnerable and the most logical points to assault. Hence it is quite natural that the southwest corner bore the brunt of the Assyrian attack.

Upon arrival at Lachish, the Assyrian army must have pitched its camp, as was the common practice in Assyrian campaigns. It must have been a large camp, providing  facilities for the expeditionary force and accommodating the king’s retinue and headquarters (cf. 2 Chronicles 32:9). Assyrian military camps are often portrayed schematically in Assyrian reliefs; they were generally round or elliptical in plan and surrounded by a fence or a wall. In some portrayals a central track is shown extending across the camp, and in others it is divided into four parts by two bisecting tracks. The camp constructed at Lachish is portrayed in a similar fashion in the “Lachish reliefs” to be discussed below.

facilities for the expeditionary force and accommodating the king’s retinue and headquarters (cf. 2 Chronicles 32:9). Assyrian military camps are often portrayed schematically in Assyrian reliefs; they were generally round or elliptical in plan and surrounded by a fence or a wall. In some portrayals a central track is shown extending across the camp, and in others it is divided into four parts by two bisecting tracks. The camp constructed at Lachish is portrayed in a similar fashion in the “Lachish reliefs” to be discussed below.

It seems that the site of the Assyrian camp can be fixed with much certainty. Strategic considerations suggest (a) that the Assyrian camp should have been located not far from the place where the main attack on the city-walls was to be launched; (b) that it should have been near the city but beyond the range of fire from the city-walls; (c) that it should not have been topographically lower than, or tactically dominated by, the city-walls; and (d) that the site of the camp should have been relatively flat and spacious, sufficiently large to accommodate the expeditionary force and the king’s headquarters. The above criteria fit the hillock to the southwest of the mound, where the Israeli village Moshav Lachish is now located. Since this hillock is connected to the mound by the saddle described above, the approach to the city was fairly easy, and the camp was located opposite the place where the main attack was to take place. This hillock is relatively high and its summit broad and flat, rising nearly as high as the city-walls in the southwest corner. Unfortunately, the reconstruction of the Assyrian camp at this place cannot be archaeologically substantiated. Any remains of such a camp, if still preserved, are now obscured by the houses and farms of Moshav Lachish.

The excavations in the southwest corner were started in 1932, when Starkey cleared the face of the outer revetment around the entire mound. Large amounts of stones were uncovered at this spot, and the digging extended down the slope as more stones were removed. As the excavations developed, the saddle area at the foot of the southwest corner and the roadway leading up to the city-gate were cleared of many thousand tons of fallen masonry. Starkey believed that these stones collapsed from above, from the strong fortifications of the southwest corner destroyed during the Assyrian attack. We resumed the excavation of the southwest corner in 1983. It soon became apparent that the stones encountered by Starkey were irregularly heaped against the slope of the mound rather than fallen from above, and hence it became clear that they form the remains of the Assyrian siege-ramp. The excavations at our trench enabled us to reconstruct the Assyrian attack to a large degree. Although partly removed by Starkey, the siege-ramp laid at the bottom of the slope could still be studied and reconstructed. At its bottom, the sloping siege-ramp must have been about 70m (210ft) wide, and about 50m (150ft) long. The core of the siege-ramp was made entirely of heaped large stones which must have been collected in the fields around. We estimated that the stones invested in the construction of the ramp weighed 13,000 to 19,000 tons.

The stones of the upper layer of the siege-ramp were found stuck together by hard mortar. This layer was the mantle of the ramp, added on top of the loose boulders in order to create a compact surface which enabled the attacking soldiers and their siege-machines to move on solid ground. The top of the siege-ramp at the foot of the city-wall was crowned by a horizontal platform; it was made of red soil and was sufficiently wide, thus providing even ground for the Assyrian siege-machines to stand upon.To end the discussion of the siege-ramp, it has to be emphasized that the siege-ramp of Lachish is, first, the earliest siege-ramp so far uncovered in archaeological excavations, and second, the only Assyrian siege-ramp which is known today.

Above the siege-ramp were uncovered the fortifications of the southwest corner which were especially massive and strong at this vulnerable point. The outer revetment formed here a kind of tower; it was built of mud-brick on stone foundations and stood about 6m (18ft) high, preserved nearly to its original height. The tower was topped by a kind of “balcony,” protected by a mud-brick parapet, on which the defenders could stand and fight. The main city-wall extended behind and above this tower. It was preserved at this point nearly to its original height—almost 5m (15ft).

Once the defenders of the city saw that the Assyrians were constructing a siege-ramp in preparation for storming the city-walls, they started to lay down a counter-ramp inside the main city-wall. They dumped here large amounts of mound debris taken from earlier city-levels which they brought from the northeast part of the mound, and constructed a large ramp, higher than the main city-wall, which provided them with a second, new inner line of defense.

As a result of the construction of the counter-ramp, the southwest corner became the highest part of the mound. The counter-ramp undoubtedly was a very impressive rampart, its apex rising about 3m (10ft) above the top of the main city-wall. Some makeshift fence or wall, perhaps made of wood, must have crowned the rampart, but its remains were not preserved. Our soundings in the core of the counter-ramp revealed accumulation of mound debris containing much earlier pottery, as well as limestone chips, which was dumped in diagonal layers. Significantly, once the Assyrians reached the walls and overcame the defense, they extended the siege-ramp over the ruined city-wall—we called it the “second stage” of the siege-ramp—to enable the attack on the newly-formed, higher defense line on the counter-ramp.

Turning to weapons and ammunition used in the battle, I shall first mention the siege-machine, the formidable weapon used by the Assyrians to destroy the defense line on the walls. No fewer than seven siege-machines arrayed for battle on top of the siege-ramp and near the city-gate are portrayed in the Lachish reliefs. The siege-machine moved on four wheels, partly protected by its body, which was made in six or more separate sections for easy dismantling and reassembling. The ram, made of a wooden beam reinforced with a sharp metal point, was probably suspended from one or more ropes, like a pendulum, and several crouching soldiers must have moved it backwards and forwards. As shown in the relief, the Judahite defenders standing on the wall were throwing flaming torches on the siege-machines. As a counter-measure, Assyrian soldiers standing on the roof of the siege-machines were pouring water from long ladles on the façade of the machines to prevent them from catching fire. The relief emphasizes the fact that the fighting between the two sides took place at close quarters, something very difficult for us to imagine at the present time when long-range guns and missiles form the main weapons.

Turning to weapons and ammunition used in the battle, I shall first mention the siege-machine, the formidable weapon used by the Assyrians to destroy the defense line on the walls. No fewer than seven siege-machines arrayed for battle on top of the siege-ramp and near the city-gate are portrayed in the Lachish reliefs. The siege-machine moved on four wheels, partly protected by its body, which was made in six or more separate sections for easy dismantling and reassembling. The ram, made of a wooden beam reinforced with a sharp metal point, was probably suspended from one or more ropes, like a pendulum, and several crouching soldiers must have moved it backwards and forwards. As shown in the relief, the Judahite defenders standing on the wall were throwing flaming torches on the siege-machines. As a counter-measure, Assyrian soldiers standing on the roof of the siege-machines were pouring water from long ladles on the façade of the machines to prevent them from catching fire. The relief emphasizes the fact that the fighting between the two sides took place at close quarters, something very difficult for us to imagine at the present time when long-range guns and missiles form the main weapons.

Two more unique finds are apparently associated with the attempts of the defenders to destroy the siege-machines. The first one includes twelve perforated stones which were discovered at the foot of both city-walls. These are large perforated stone blocks, with a flat top, straight sides, and an irregular bottom. Each of them is nearly 60cm (2ft) in diameter and weighs about 100 to 200kg. Remains of burnt, relatively thin ropes were found in the holes of two stones.

As indicated by the remains of the ropes, it seems that the perforated stones were tied to ropes and lowered by the defenders from the city-wall. I assume that these stones were lowered from some makeshift installation, such as a thick wooden beam projecting from the line of the wall. The defenders probably used the stones in an attempt to damage the siege-machines and prevent the rams from hitting the wall; they must have dropped the stones on the siege-machines and swung them to and fro like a pendulum.

The second find is a fragment of an iron chain containing four long, narrow links, which was uncovered in the burnt mud-brick debris in front of the outer revetment. The defenders probably used the iron chain in order to unbalance the siege-machines. We assume that they lowered the chain below the point of thrust of the ram in order to catch its shaft when it reached the wall, and then raised the chain.

Some of the ammunition used in the battle was also found. The Lachish reliefs display Assyrian slingers shooting at the walls as well as Judahite defenders shooting sling stones at the attackers, and many sling stones were indeed found in the excavations. These are well-shaped balls of flint or limestone, resembling tennis balls, and weighing about 250 grams or more.

The Lachish reliefs display Assyrian archers supporting the attack on the walls, and indeed close to one thousand arrowheads were discovered in the excavation of the southwest corner. The arrowheads are not uniform in size or shape, and different types are represented. Almost all of them were made of iron, and a few were cast of bronze or carved of bone. In some cases ashes, the remains of the wooden shafts of the arrows, could still be discerned when exposed in the excavation. Most of the arrowheads were uncovered in the burnt mud-brick debris in front of the city-walls. Apparently these arrows were shot by Assyrian archers at the Judahite warriors standing on the “balconies” on top of the walls. The discovery of so many arrowheads in such a small area indicates how concentrated the Assyrian firepower was. Many arrowheads were found bent—an indication that they were shot at the walls with powerful bows from close range.

Unfortunately, the archaeological data are insufficient to answer three basic questions: what was the size of the city’s population at the time of the siege; what was the size of the Assyrian force; and how long did the siege last? Regarding the number of inhabitants and defenders, we can only make a rough estimate. The accepted method for estimating the size of the population in an ancient settlement is by multiplying the settled area by a density coefficient. Adopting the coefficient of 100 people per acre used by Broshi and Finkelstein in their study of the Iron II period it follows that fewer than 2000 people lived at Lachish at that time. However, this method is meant to estimate the population in a regular settlement, while Lachish was mainly a military, fortified center. Moreover, it is possible that the number of people in Lachish changed on the eve of the siege, either because people from the surrounding region took refuge here, or due to changes being made in the deployment of the Judahite army.

Unfortunately, the archaeological data are insufficient to answer three basic questions: what was the size of the city’s population at the time of the siege; what was the size of the Assyrian force; and how long did the siege last? Regarding the number of inhabitants and defenders, we can only make a rough estimate. The accepted method for estimating the size of the population in an ancient settlement is by multiplying the settled area by a density coefficient. Adopting the coefficient of 100 people per acre used by Broshi and Finkelstein in their study of the Iron II period it follows that fewer than 2000 people lived at Lachish at that time. However, this method is meant to estimate the population in a regular settlement, while Lachish was mainly a military, fortified center. Moreover, it is possible that the number of people in Lachish changed on the eve of the siege, either because people from the surrounding region took refuge here, or due to changes being made in the deployment of the Judahite army.

As to the size of the Assyrian army encamped at Lachish, or the size of the force which took part in the attack on the city, no data are available. As to the question of how long the siege of the city lasted, it apparently was a brief siege, as the entire Assyrian campaign lasted for only part of one year. During that period of time, the Assyrian army marched from Assyria to Judah, subjugated Phoenicia and Philistia, fought the Egyptian expeditionary force, conquered part of Judah, and returned home. It seems that most of the time needed for the attack on Lachish was spent in laying the siege-ramp, while the attack on the city-walls was relatively brief. Ephʿal tried to calculate the time needed for laying the siege-ramp, and suggested that it took twenty-three days.8 However, all the basic data needed for the calculations, such as the quantity of stones dumped in the siege-ramp, the distance from where they were taken, the number of porters employed in carrying them, and the delays caused by opposition of the defenders, can only be surmised.