Senaquerib governou a Assíria durante 24 anos, de 705 a 681 a.C. No quarto ano de seu reinado, em 701 a.C., ele partiu para a Fenícia e a Palestina em sua terceira campanha militar. Seus alvos foram Lulî, rei de Sidon; Ṣidqâ, da cidade de Ascalon; os nobres e os habitantes da cidade de Ekron e seus aliados egípcios e etíopes; Ezequias, rei de Judá em Jerusalém.

Em meu artigo sobre O contexto da Obra Histórica Deuteronomista escrevi:

Em 701 a.C. Senaquerib começou por Tiro, vencendo-a. Logo os reis de Biblos, Arvad, Ashdod, Moab, Edom e Amon se entregaram e pagaram tributo a Senaquerib. Somente Ascalon e Ekron, juntamente com Judá, resistiram. Senaquerib tomou primeiro Ascalon. Os egípcios tentaram socorrer Ekron e foram derrotados. E foi a vez de Judá. Senaquerib tomou 46 cidades fortificadas em Judá e cercou Jerusalém.

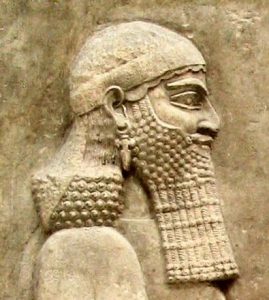

Testemunhos arqueológicos da devastação foram encontrados em várias escavações por todo o território. Especialmente significativos são a representação assíria da tomada de Laquis encontrada no palácio de Senaquerib em Nínive – hoje está no British Museum – e a escavação, feita pelos britânicos na década de 30 e por David Ussishkin, da Universidade de Tel Aviv, na década de 70 do século XX, da poderosa fortaleza, esta que era a segunda mais importante cidade do reino e protegia a entrada de Judá.

tomada de Laquis encontrada no palácio de Senaquerib em Nínive – hoje está no British Museum – e a escavação, feita pelos britânicos na década de 30 e por David Ussishkin, da Universidade de Tel Aviv, na década de 70 do século XX, da poderosa fortaleza, esta que era a segunda mais importante cidade do reino e protegia a entrada de Judá.

Entretanto, por motivos ainda hoje desconhecidos, talvez uma peste, Senaquerib levantou o cerco de Jerusalém e retornou à Assíria. A cidade voltou a respirar, no último minuto, mas teve que pagar forte tributo aos assírios. Não se sabe porque Jerusalém se salvou. 2Rs 19,35-37 diz que o Anjo de Iahweh atacou o acampamento assírio. Existe uma notícia de Heródoto, História II,141, segundo a qual num confronto com os egípcios os exércitos de Senaquerib foram atacados por ratos (peste bubônica?). Talvez Senaquerib tenha partido por causa de alguma rebelião na Mesopotâmia. Ou ainda: há autores que pensam que Jerusalém nem precisou ser sitiada para ser vencida. Nos Anais de Senaquerib se diz o seguinte: “Quanto a Ezequias do país de Judá, que não se tinha submetido ao meu jugo, sitiei e conquistei 46 cidades que lhe pertenciam (…) Quanto a ele, encerrei-o em Jerusalém, sua cidade real, como um pássaro na gaiola…”.

ELAYI, J. Sennacherib, King of Assyria. Atlanta: SBL, 2018, p. 76-81 diz:

O cerco de Jerusalém por Senaquerib em 701 a.C. é uma questão difícil, principalmente por causa das contradições entre as fontes assírias e bíblicas.

Muitos autores pensam que não houve um cerco de Jerusalém, mas somente um bloqueio da capital que ficou isolada do resto do país. Como dão a entender os Anais de Senaquerib que dizem: Quanto a ele (Ezequias), eu o confinei (e-sir-šu) dentro da cidade de Jerusalém, sua cidade real, como um pássaro em uma gaiola. Montei bloqueios (ḫal-ṣu.MEŠ) contra ele e o fiz ter pavor de sair pela porta da cidade.

Um bloqueio de Jerusalém cortaria suprimentos e deixaria a cidade sem qualquer socorro externo. O objetivo era fazer Ezequias se render. Enquanto isso o exército assírio poderia continuar a conquista do território.

Teria Senaquerib sido incapaz de tomar Jerusalém? Seriam as técnicas de cerco assírias não tão avançadas como se alardeava? Ou seria Jerusalém muito bem fortificada? Mas se Senaquerib conquistou Laquis, por que não poderia fazer o mesmo com Jerusalém? Além do que, técnicas de bloqueio já tinham sido usadas por Tiglat-Pileser III, avô de Senaquerib, contra o rei Rezin de Damasco.

Por outro lado, os textos bíblicos em 2Rs 18,13-19,37; Is 36-37; 2Cr 32 trazem várias informações que não estão nas textos assírios de que dispomos. Ezequias se prepara militarmente, melhora suas defesas, negocia com emissários assírios, embora tal negociação pareça, pela linguagem usada, ser coisa mais dos redatores dos textos bíblicos do que um fato histórico.

Como consequência do bloqueio, Judá perdeu territórios para os filisteus, segundo os textos assírios. E isto é plausível, pois a prática assíria de tirar partes do território de vassalos rebeldes e entregá-las a reis leais é conhecida.

O resultado do bloqueio é a submissão de Ezequias a Senaquerib e o pagamento de pesado tributo, um dos maiores de todos os citados nas várias campanhas militares de Senaquerib.

Uma questão continua sendo debatida: por que Ezequias envia o tributo após a volta de Senaquerib para Nínive, como narram as fontes assírias?

Alguns acham que, por Ezequias aceitar pagar o tributo, Senaquerib pode voltar ao seu país, pois o pagamento estava, nas circunstâncias, garantido. Outros acham que Ezequias quer, com o envio do tributo, evitar outro ataque de Senaquerib.

Mas, pode-se também entender a coisa toda na dinâmica das guerras da época: Senaquerib volta a Nínive com a cavalaria e sua guarda pessoal, antes da infantaria de seu exército que se move mais lentamente, com os produtos do saque em carros de boi e os prisioneiros de guerra em lentas montarias ou a pé.

Entretanto é mais provável que os assírios tenham deixado tropas no território, que poderiam retaliar caso Ezequias não demonstrasse submissão pagando o tributo.

E agora a questão principal: por que Senaquerib deixa Jerusalém sem destruí-la?

Os textos assírios não o dizem, mas os relatos bíblicos sim.

O debate acadêmico tem trabalhado 4 aspectos dos relatos bíblicos:

1. 2Rs 18,13-16 – o pagamento do tributo teria levado ao recuo de Senaquerib. Mas se o tributo foi pago posteriormente em Nínive, não teria sido isso que levou ao recuo do rei assírio

2. 2Rs 19,7 – a profecia de Isaías, mas isto é teologia, não história

3. 2Rs 19, 8-9 – uma intervenção egípcia, mas mesmo que isso tivesse acontecido, por que Senaquerib se retiraria do território?

4. 2Rs 19,35-36 – a ação do Anjo de Iahweh, que pode ser uma versão teológica da praga de ratos relatada por Heródoto – mas a autora considera o argumento circular, pois Heródoto é usado para explicar o relato bíblico e vice-versa.

Ou seja: nenhum aspecto dos relatos bíblicos explica realmente o que aconteceu.

Os textos assírios e bíblicos nos deixam ver duas ideologias em confronto: do ponto de vista assírio, Senaquerib é o poderoso rei que nunca sofre uma derrota; do ponto de vista bíblico, Ezequias é o rei fiel a Iahweh que é por ele socorrido.

E se a política assíria tivesse como objetivo apenas quebrar a força da rebelião na região, como fazia rotineiramente em outras situações, e não destruir tudo?

O que para Judá pode ter parecido um grande evento militar, era coisa corriqueira para a Assíria, tal a diferença de forças em jogo.

Mas e Laquis? Laquis pode ter sido destruída para servir de exemplo de como resistir era inútil.

Com a perda do território da Sefelá, Judá ficou sem o controle da rota comercial para o Egito. Ficou arrasado economicamente. Mas um Judá submisso ainda preenchia, junto com as cidades filisteias, a função de estado tampão com o Egito.

E a ameaça babilônica, neutralizada na campanha seguinte, em 700 a.C. poderia ser a que realmente preocupava Senaquerib.

Dizem os Anais de Senaquerib:

The Chicago/Taylor Prism

(iii 18) Moreover, (as for) Hezekiah of the land Judah, who had not submitted to my yoke, I surrounded (and) conquered forty-six of his fortified cities, (iii 20) fortresses, and small(er) settlements in their environs, which were without number, by having ramps trodden down and battering rams brought up, the assault of foot soldiers, sapping, breaching, and siege engines. I brought out of them 200,150 people, young (and) old, male and female, (iii 25) horses, mules, donkeys, camels, oxen, and sheep and goats, which were without number, and I counted (them) as booty.

(iii 27b) As for him (Hezekiah), I confined him inside the city Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage. I set up blockades against him and (iii 30) made him dread exiting his city gate. I detached from his land the cities of his that I had plundered and I gave (them) to Mitinti, the king of the city Ashdod, Padî, the king of the city Ekron, and Ṣilli-Bēl, the king of the city Gaza, and (thereby) made his land smaller. (iii 35) To the former tribute, their annual giving, I added the payment (of) gifts (in recognition) of my overlordship and imposed (it) upon them (text: “him”).

(iii 37b) As for him, Hezekiah, fear of my lordly brilliance overwhelmed him and, after my (departure), he had the auxiliary forces and his elite troops whom (iii 40) he had brought inside to strengthen the city Jerusalem, his royal city, thereby gaining reinforcements, along with 30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver, choice antimony, large blocks of …, ivory beds, armchairs of ivory, elephant hide(s), elephant ivory, (iii 45) ebony, boxwood, every kind of valuable treasure, as well as his daughters, his palace women, male singers, (and) female singers brought into Nineveh, my capital city, and he sent a mounted messenger of his to me to deliver (this) payment and to do obeisance.

The Jerusalem Prism

(iii 18) Moreover, (as for) Hezekiah of the land Judah, who had not submitted to my yoke, I surrounded (and) conquered forty-six of his fortified cities, (iii 20) fortresses, and small(er) settlements in their environs, which were without number, by having ramps trodden down and battering rams brought up, the assault of foot soldiers, sapping, breaching, and siege engines. I brought out of them 200,150 people, young (and) old, male and female, (iii 25) horses, mules, donkeys, camels, oxen, and sheep and goats, which were without number, and I counted (them) as booty.

(iii 27b) As for him (Hezekiah), I confined him inside the city Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage. I set up blockades against him and (iii 30) made him dread exiting his city gate. I detached from his land the cities of his that I had plundered and I gave (them) to Mitinti, the king of the city Ashdod, Padî, the king of the city Ekron, and Ṣilli-Bēl, the king of the city Gaza, and (thereby) made his land smaller. (iii 35) To the former tribute, their annual giving, I added the payment (of) gifts (in recognition) of my overlordship and imposed (it) upon them (text: “him”).

(iii 37b) As for him, Hezekiah, fear of my lordly brilliance overwhelmed him and, after my (departure), he had the auxiliary forces and his elite troops whom (iii 40) he had brought inside to strengthen the city Jerusalem, his royal city, thereby gaining reinforcements, along with 30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver, choice antimony, large blocks of …, ivory beds, armchairs of ivory, elephant hide(s), elephant ivory, (iii 45) ebony, boxwood, every kind of valuable treasure, as well as his daughters, his palace women, male singers, (and) female singers brought into Nineveh, my capital city, and he sent a mounted messenger of his to me to deliver (this) payment and to do obeisance.

Rassam Cylinder

(49) (As for) Hezekiah of the land Judah, I surrounded (and) conquered forty-six of his fortified walled cities and small(er) settlements in their environs, which were without number, (50) by having ramps trodden down and battering rams brought up, the assault of foot soldiers, sapping, breaching, and siege engines. I brought out of them 200,150 people, young (and) old, male and female, horses, mules, donkeys, camels, oxen, and sheep and goats, which were without number, and I counted (them) as booty.

(52) As for him (Hezekiah), I confined him inside the city Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage. I set up blockades against him and made him dread exiting his city gate. I detached from his land the cities of his that I had plundered and I gave (them) to Mitinti, the king of the city Ashdod, and Padî, the king of the city Ekron, (and) Ṣilli-Bēl, the king of the land Gaza, (and thereby) made his land smaller. To the former tribute, their annual giving, I added the payment (of) gifts (in recognition) of my overlordship and imposed (it) upon them.

(55) As for him, Hezekiah, fear of my lordly brilliance overwhelmed him and, after my (departure), he had the auxiliary forces (and) his elite troops whom he had brought inside to strengthen the city Jerusalem, his royal city, thereby gaining reinforcements, (along with) 30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver, choice antimony, large blocks of …, ivory beds, armchairs of ivory, elephant hide(s), elephant ivory, ebony, boxwood, garments with multi-colored trim, linen garments, blue-purple wool, red-purple wool, utensils of bronze, iron, copper, tin, (and) iron, chariots, shields, lances, armor, iron belt-daggers, bows and uṣṣu-arrows, equipment, (and) implements of war, (all of) which were without number, together with his daughters, his palace women, male singers, (and) female singers brought into Nineveh, my capital city, and he sent a mounted messenger of his to me to deliver (this) payment and to do obeisance.

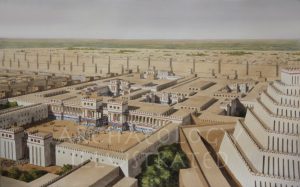

Vídeos sobre Nínive, o palácio de Senaquerib em Nínive e a tomada de Laquis:

3D Digital Art Ancient Nineveh – Ashurbanipal, Assyria – 3D by Kais Jacob – 18 de março de 2016

Flyover of the ancient citadel at Nineveh – Learning Sites – 28 de novembro de 2017

Southwest Palace, Nineveh, flyover and flythrough showing Carlos Museum fragments in context – Learning Sites – 2 de maio de 2019

The Lachish Reliefs – Megalim Institute – 2 de dezembro de 2013