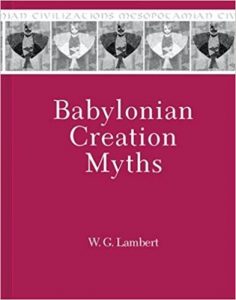

Em 2017 “fui morar” por muitos meses na antiga Mesopotâmia para escrever um texto sobre Histórias de criação e dilúvio na antiga Mesopotâmia. E então conheci alguns textos do extraordinário assiriólogo britânico Wilfred George Lambert (1926-2011). Entre eles o atual texto acadêmico padrão do Enuma Elish: LAMBERT, W. G. Babylonian Creation Myths. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2013.

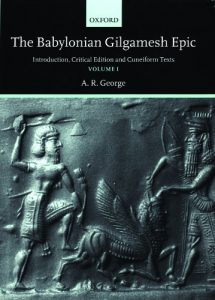

E também conheci textos de seu ex-aluno Andrew R. George, assiriólogo da Universidade de Londres e autor do texto acadêmico padrão da Epopeia de Gilgámesh: GEORGE, A. R. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Andrew George publicou em 2015 uma fascinante memória biográfica de Wilfred George Lambert para a British Academy. O texto está disponível online.

GEORGE, A. R. Wilfred George Lambert 1926-2011. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, XIV, 337–359, 2015.

Vou transcrever alguns trechos aqui.

Depois de traçar o perfil intelectual de Lambert ao longo de 20 páginas, A. R. George, diz nas páginas 356-359:

Nestes parágrafos finais tentarei dar uma rápida ideia do caráter de um homem que será sempre lembrado como o mais brilhante assiriólogo britânico de sua época. Após a morte de seus pais, o único parente próximo de Lambert foi sua irmã mais velha, Muriel, que era quatro anos mais velha do que ele. Ambos permaneceram solteiros e sem filhos. Parece que a deusa Ishtar falhou em capturar suas emoções. Sua vida social foi dividida entre a Universidade de Birmingham e a Igreja Cristadelfiana da cidade. Na universidade ele frequentava regularmente as reuniões e estava sempre disposto a prolongar a noite em um restaurante indiano. Para as congregações cristadelfianas ele dava palestras sobre a Bíblia a partir da perspectiva do Antigo Oriente Médio.

Lambert era movido por uma enorme sede de conhecimento e se media com seus contemporâneos a partir disso. Só eloquência não o impressionava. Certa vez ele comentou sobre uma palestra de um arqueólogo: “Ele fala muito bem, mas não tenho certeza de que ele tenha realmente dito alguma coisa”. Para ele, a pergunta mais importante, que ele fazia para qualquer texto ou palestra acadêmica, era: “Isso me ensina algo que eu não sabia antes”? Os julgamentos feitos em resposta a essa pergunta às vezes combinavam com sua particular incapacidade de evitar uma opinião franca e direta. Isso o levava a conquistar inimigos sem querer. Embora sociável até certo ponto, ele não era um indivíduo muito falante. Possivelmente sua formação o excluía de estar à vontade na companhia de contemporâneos que ele achava que eram mais favorecidos pelo nascimento. Ele zombava dos sobrenomes alemães prefixados com ‘von’, não apenas por rivalidade com seu adversário de Münster, Wolfram von Soden, mas também porque o cristadelfianismo havia incutido nele uma antipatia pela hierarquia social.

Parece ter sido um solitário por opção. Daí que ele não tinha pessoas próximas a ele para desabafar e para o consolar quando sofria injustiças. Ele desabafava escrevendo cartas de reclamação. Ele sempre mantinha cópias em carbono. Em sua mesa, por ocasião de sua morte, havia uma correspondência com um operador ferroviário por causa de seu mau serviço, e outra com uma empresa de alimentos sobre a quantidade de grãos integrais realmente existentes em um pãozinho descrito como integral na embalagem. Mais revelador foi um dossiê de cartas de e para colegas acadêmicos, no qual ele usava linguagem franca e direta, denegrindo amargamente terceiros que ele achava que o haviam prejudicado.

Quando seu orgulho profissional não corria perigo, ele era muito mais agradável. Em seu serviço de ação de graças, Anthony Watkins, um amigo cristadelfiano, fez um discurso que se inspirava nas lembranças de muitos cristadelfianos que conheceram Lambert. Eles observaram as qualidades que estavam em evidência em sua carreira acadêmica, incluindo ‘clareza de pensamento e exposição’, ‘pensamento claro e instinto aparentemente infalível para o que era certo’. Eles também se lembraram de um homem ‘quieto e reservado’ que era ‘infalivelmente encantador, modesto e simples’ e que ‘nunca exibia suas habilidades’. Muitos colegas acadêmicos também conheciam esse lado dele. De fato, a modéstia pessoal foi o atributo mais destacado no caráter de Lambert. Muitas pessoas com muito menos importância causavam um furor maior, mas ele rejeitava a autopromoção e a vaidade onde quer que as encontrasse.

Até a doença de seus últimos anos, sua saúde era excelente. Mesmo no início dos anos oitenta, ele andava mais rápido e ia mais longe do que muitas pessoas muito mais jovens. Suas costas desenvolveram uma protuberância, mas isso não pareceu incomodá-lo. Um colega alemão escreveu cartas insistindo que havia um tratamento simples e eficaz. Lambert manteve as cartas, mas não parece ter seguido o conselho. Provavelmente ele não teve tempo para tal. Quando um câncer finalmente começou a afetar sua vitalidade, ele se queixou impaciente a vários correspondentes da mobilidade reduzida que estava sofrendo. A doença era difícil de suportar, não apenas porque era estranha para ele, mas também porque atrapalhava seu trabalho.

Ele não saía de férias, mas geralmente participava do Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale (RAI), o congresso internacional anual de assiriologia. Assim, ele encontrava boa parte do mundo acadêmico de sua área. Ele se orgulhava de escrever anotações para suas palestras em pequenos pedaços de papel enquanto viajava para o local. Suas apresentações tinham precisão, clareza e humor e sempre atraíam grandes audiências. Ás vezes seu fino humor aparecia também em suas publicações.

A frugalidade de Lambert era bem conhecida. Sua vida doméstica era espartana. Ele foi vegetariano durante toda a vida e achava desnecessária uma cozinha bem aparelhada. Ele não possuía carro ou televisão. Ele também não ouvia o rádio que sua irmã lhe deu, escondendo-o atrás de um guarda-roupa. Ele lia as notícias do Daily Telegraph. Nos anos 90 ele tentou substituir sua velha máquina de escrever manual por um computador pessoal, mas, ao comprá-lo, não encontrou ninguém que pudesse lhe explicar em vocabulário não técnico como usá-lo. A experiência confirmou sua aversão por aparelhos eletrônicos e recursos tecnológicos.

Seus passatempos consistiam em tocar piano, manter sua biblioteca acadêmica atualizada e colecionar selos cilíndricos do Antigo Oriente Médio. Ele falava com orgulho que sua coleção de selos era, de certa forma, superior em qualidade à do Museu Britânico. Antes de sua morte, ele providenciou a transferência da coleção para o Museu Britânico. Assim, ele aprimorou as coleções do museu por meio de um ato de generosidade incomum, além das décadas de notável pesquisa que ali fez. Foi o seu momento mais nobre.

Seus passatempos consistiam em tocar piano, manter sua biblioteca acadêmica atualizada e colecionar selos cilíndricos do Antigo Oriente Médio. Ele falava com orgulho que sua coleção de selos era, de certa forma, superior em qualidade à do Museu Britânico. Antes de sua morte, ele providenciou a transferência da coleção para o Museu Britânico. Assim, ele aprimorou as coleções do museu por meio de um ato de generosidade incomum, além das décadas de notável pesquisa que ali fez. Foi o seu momento mais nobre.

W. G. Lambert morreu no Hospital Queen Elizabeth, em Birmingham, em 9 de novembro de 2011. Foi cremado em 25 de novembro no Lodge Hill Cemetery, após um serviço de ação de graças no West Birmingham Christadelphian Hall, em Quinton. Ele deixou a maior parte de sua biblioteca acadêmica para sua alma mater, Christ’s College, em Cambridge. Os livros agora estão na Biblioteca Haddon do Departamento de Arqueologia e Antropologia da Universidade. Ele deixou seus bens para as Casas Cristadelfianas de Assistência, uma instituição de caridade que cuidou de sua irmã e de muitos de seus amigos na velhice.

A few last paragraphs will attempt to give a rounded impression of the character of a man who will always be recalled as the most brilliant British Assyriologist of his era. After the death of his parents Lambert’s only close relative was his elder sister, Muriel, who was four years older than him. Both remained unmarried and childless. It seems the goddess Ishtar failed to capture his emotions, just as she thwarted his ambitions in Tablet IV of the god-list An = Anum. His social life was divided between the University of Birmingham and the city’s Christadelphian Ecclesiae, first Birmingham Central and later West Birmingham. At the university he was a regular in the senior common room and always ready after visitors’ lectures to prolong the evening in the Indian restaurants of Selly Oak. To Christadelphian congregations he gave talks on the Bible from ancient Near Eastern perspectives.

Lambert was driven by a thirst for knowledge and measured himself against his contemporaries accordingly. Eloquence alone left him unimpressed. He once remarked  after a conference address delivered by an archaeologist, ‘He speaks well enough, but I am not sure that he actually said anything.’ For him the key question that he brought to any piece of academic writing or lecture was, ‘Does this teach me anything I did not know before?’ Judgements made in response to this question sometimes combined with his distinctive inability to suppress forthright opinion. This could colour social relations with fellow academics; he made enemies unwittingly. Though sociable to a point, he was not a clubbable individual. Possibly his background excluded him from being at ease in the company of contemporaries whom he felt had been better favoured by birth. He made fun of German surnames prefixed with ‘von’, not only out of rivalry with his adversary in Münster but also because Christadelphianism had instilled in him an antipathy to social hierarchy.

after a conference address delivered by an archaeologist, ‘He speaks well enough, but I am not sure that he actually said anything.’ For him the key question that he brought to any piece of academic writing or lecture was, ‘Does this teach me anything I did not know before?’ Judgements made in response to this question sometimes combined with his distinctive inability to suppress forthright opinion. This could colour social relations with fellow academics; he made enemies unwittingly. Though sociable to a point, he was not a clubbable individual. Possibly his background excluded him from being at ease in the company of contemporaries whom he felt had been better favoured by birth. He made fun of German surnames prefixed with ‘von’, not only out of rivalry with his adversary in Münster but also because Christadelphianism had instilled in him an antipathy to social hierarchy.

It seems he was solitary by choice; in consequence he lacked people close to him who might have listened to his grievances and tempered his outrage when his sense of injustice was violated. He could accuse others of spite where none existed, even in print. He let off steam by writing letters of complaint. He always kept carbon copies. On his desk at the time of his death was a correspondence with a railway operator over its poor service, and another with a grocery company over the amount of whole grain actually in a bread roll described as wholegrain on the packaging. More telling was a dossier of letters to and from fellow academics, in which he used frank language and not a little vitriol to denigrate third parties whom he thought had wronged him.

When his professional pride was not in danger of hurt, he was much more congenial. At his service of thanksgiving Anthony Watkins, a Christadelphian friend, gave an address that drew on the recollections of many Christadelphians who had known Lambert. They remarked on qualities that were much in evidence in his academic career, including ‘clarity of thought and exposition’, ‘clear thinking and seemingly unerring instinct for what was right’. They also recalled a ‘quiet and undemonstrative’ man who was ‘unfailingly charming, modest and self-effacing’ and ‘never paraded his abilities’. Many academic colleagues knew this side of him too. Indeed, personal modesty was the most salient attribute in Lambert’s character. Many people of much less distinction have made a bigger splash, but self-promotion and vanity repelled him wherever he found them.

Until the illness of his last few years, his physical health was excellent. Even in his early eighties he walked faster and further than many much younger people. His back developed a hump, but it did not seem to trouble him. A German colleague wrote letters insisting that there was simple and effective treatment. Lambert kept the letters but does not seem to have taken the advice. Probably he had no time to spare. When a cancer finally began to affect his vitality, he complained impatiently to several correspondents of the reduced mobility that he was suffering. Ill health was difficult to endure, not only because it was strange to him but also because it stood between him and his work.

He did not go on holiday, but usually attended the annual Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, the peripatetic international conference for Assyriology. Thus he saw a good deal of the world and its universities. He took pride in writing notes for his conference papers on small pieces of paper while travelling to the venue. The results were delivered extempore with precision, clarity and humour, and always drew large audiences. More rarely his wit was expressed in print. In an early essay on ‘Morals in Ancient Mesopotamia’ he cited a passage of Gilgamesh XII which promises better treatment in the netherworld for those who had large families while living. ‘The family allowances of the ancients,’ he observed, ‘were apparently not paid until death.’

Lambert’s frugality was well known. He was not above picking up a penny in the street. His home life was spartan. He was a lifelong vegetarian and found modern kitchen equipment unnecessary. He did not own a car or a television. Nor did he listen to the radio that his sister gave him, placing it out of sight at the back of a wardrobe. He got his news from the Daily Telegraph. In the 1990s he attempted to replace his old manual typewriter with a personal computer, but having bought one could find nobody who could explain to him in non-technical vocabulary how to use it. The experience confirmed his aversion to electrical gadgets and technological aids.

Lambert’s frugality was well known. He was not above picking up a penny in the street. His home life was spartan. He was a lifelong vegetarian and found modern kitchen equipment unnecessary. He did not own a car or a television. Nor did he listen to the radio that his sister gave him, placing it out of sight at the back of a wardrobe. He got his news from the Daily Telegraph. In the 1990s he attempted to replace his old manual typewriter with a personal computer, but having bought one could find nobody who could explain to him in non-technical vocabulary how to use it. The experience confirmed his aversion to electrical gadgets and technological aids.

His pastimes were playing the piano, keeping his academic library up to date and collecting ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals. He maintained with pride that his collection of seals was by some distance superior in quality to that of the British Museum. Before his death he arranged for its transfer to the British Museum as a bequest. Thus he enhanced the useum’s collections through an act of unusual generosity as well as through decades of remarkable scholarship. It was his noblest moment.

W. G. Lambert died at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham on 9 November 2011. He was cremated on 25 November at Lodge Hill Cemetery after a service of thanksgiving at West Birmingham Christadelphian Hall in Quinton. He left most of his academic library to his alma mater, Christ’s College, Cambridge. The books are now housed in the Haddon Library of the University’s Department of Archaeology and Anthropology. The residue of his estate he bequeathed to the Christadelphian Care Homes, a charity that had cared for his sister and many of his friends in their old age.