The UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology is an international cooperative project to provide high quality peer reviewed information on ancient Egypt.

Confira.

Blog sobre estudos acadêmicos da Bíblia

The UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology is an international cooperative project to provide high quality peer reviewed information on ancient Egypt.

Confira.

Um leitor me pergunta a propósito do post de 19 de outubro de 2017, Akitu – Festival do Ano Novo na Babilônia:

Se aconteciam duas celebrações em tempos distintos onde estão os relatos das celebrações de outono? Ou eles repetiam a mesma ritualística duas vezes ao ano? E mesmo que o fizessem quais seriam as diferenças, pois uma era para colher e outra para plantar?

Uma boa leitura, de pouco mais de 50 páginas, embora bastante técnica, pode ser feita em:

COHEN, M. E. The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East. Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press, 1993, p. 400-453.

O bom é que o livro está disponível para download gratuito em The Internet Archive.

Confira aqui.

DEVER, W. G. Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2017, 772 p. – ISBN 9780884142188.

William G. Dever offers a welcome perspective on ancient Israel and Judah that prioritizes the archaeological remains to render history as it was — not as the biblical writers argue it should have been. Drawing from the most recent archaeological data as interpreted from a non theological point of view and supplementing that data with biblical material only when it converges with the archaeological record, Dever analyzes all the evidence at hand to provide a new history of ancient Israel and Judah that is accessible to all interested readers.

Features:

. A new approach to the history of ancient Israel

. Extensive bibliography

. More than eighty maps and illustrations

William G. Dever is Distinguished Visiting Professor at Lycoming College in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, and Professor Emeritus at the Arizona Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Arizona.

Sobre o projeto

Neo-Babylonian Cuneiform Corpus (NaBuCCo) é um site que pretende colocar metadados textuais online de cerca de 20.000 documentos neobabilônicos publicados, incluindo registros legais, administrativos e epistolares. Estes documentos foram criados no I milênio a. C. e se originaram principalmente de cinco grandes cidades da Mesopotâmia durante esse período: Babilônia, Borsippa, Nippur, Sippar e Uruk. O site coleta todos os dados meta textuais das fontes, parafraseia seu conteúdo, disponibiliza os dados online e os liga, através de sites parceiros, aos documentos originais dos quais são extraídos. Além do catálogo de texto, o projeto oferece uma bibliografia detalhada e abrangente sobre a Babilônia no primeiro milênio a. C.

Espera-se que o projeto beneficie os pesquisadores. Na verdade, o banco de dados, com sua ferramenta de pesquisa avançada, páginas interligadas e extensa bibliografia, permitirá que estudiosos do campo da assiriologia e também de outros campos da pesquisa histórica de todo o mundo trabalhem com uma coleção abrangente de textos babilônicos em seus próprios projetos. Espera-se também que o catálogo, a bibliografia e o portal NaBuCCo sejam ferramentas úteis para levar o mundo da Babilônia até os não especialistas. Este portal fornecerá informações consistentes sobre cronologia e eventos históricos, principais cidades e topografia, vários aspectos da sociedade e da economia da Babilônia do I milênio a. C. e estabelece as bases para a compreensão dos próprios textos apresentados. O usuário comum também encontrará explicações básicas sobre os tipos e a origem dos textos apresentados.

A equipe é formada por pesquisadores da Universidade Católica de Leuven, Bélgica, da Universidade de Viena, Áustria, e da Universidade de Tel Aviv, Israel.

About the project

NaBuCCo is a text-oriented website that aims at putting online textual metadata of an estimated 20,000 published Babylonian documentary sources including legal, administrative and epistolary records. These documents have been created between roughly 800 and the end of the pre-Christian era and primarily originate from the five large cities of Mesopotamia during that time: Babylon, Borsippa, Nippur, Sippar and Uruk along with their agrarian hinterland. The website collects all meta-textual data from the sources, paraphrases their content, makes the data available online, and links them (via partner websites) to the original source documents from which they are extracted.

In addition to the text catalogue, the project offers a comprehensive up-to-date bibliography on Babylonia in the first millennium BCE.

We hope that the project will benefit the research community. Indeed, the database with its advanced search tool, interlinked pages and extensive bibliography will enable scholars from within the field of Assyriology and also from other historical fields from all over the world to work with a comprehensive collection of Babylonian texts for their own research projects.

At the same time we hope that NaBuCCo’s catalogue, bibliography and to be developed portal will be a useful tool to delve into the Babylonian world for non-specialists. While the main addressees are specialist and non-specialists scholars, the project also aims at approaching those stakeholders who are not scientifically involved in this kind of source material. Being freely accessible online, the NaBuCCo database can not only be searched through and experienced by any historically interested individual, but – most importantly – provides proper tools, namely the paraphrases, to understand the archival texts from Babylonia also without background knowledge. The access to and the basic understanding of the Babylonian world and its thousands of texts will, furthermore, be eased by the 1st Millennium BC Babylon Portal to be provided on the NaBuCCo website in the future. This portal will provide profound information about chronology and historical events, main cities and topography, various aspects of society and economy of 1st-millinium-BCE Babylonia and lays the foundation for an understanding of the presented texts themselves. The common user will also find basic explanations about the types and origin of the texts presented.

NaBuCCo, short for Nabucodonosor (English Nebuchadnezzar), is the title of an opera by Verdi in which the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II and the exile of the Judean population induced by him play a central role. We choose this name as acronym for a scientific project coined the Neo-Babylonian Cuneiform Corpus (NaBuCCo) that aims to make available clay tablets with cuneiform script originating from Babylonia or its immediate vicinity and dated to the Age of Empires (c. 770 BCE – 75 CE), a.o. tablets dated to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (c. 605-562 BCE), who is no doubt the most famous king of one of the empires, the Neo-Babylonian (Chaldean) Empire.

The NaBuCCo project was created as part of the research project Greater Mesopotamia: Reconstruction of its Environment and History (GMREH), whose funding is provided by the Belgian Science Policy Office – BELSPO in the framework of the Interuniversity Attraction Poles (IAP) (2012-2017).

Principal investigators: Kathleen Abraham, KU Leuven; Michael Jursa, University of Vienna, and Shai Gordin, Ariel University / Tel Aviv University.

Descobri hoje que saiu no dia 10 passado o livro de Jacyntho Lins Brandão com a tradução e comentário da Epopeia de Gilgámesh. Utilizei artigos dele em meu estudo sobre as Histórias de criação e dilúvio na antiga Mesopotâmia.

BRANDÃO, J. L. Ele que o abismo viu: Epopeia de Gilgámesh. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2017, 336 p. – ISBN 9788551302835. Uma edição em capa dura, sem notas e comentários, saiu em 2021.

Esta é uma tradução comentada do poema comumente denominado “Epopeia de Gilgámesh” – cujo título original é Ele que o abismo viu (ša naqba īmuru) e cuja autoria se atribui a Sin-léqi-unnínni –, trabalho que procura beneficiar-se de tudo que, nos últimos anos, permitiu que se ampliasse nosso conhecimento, em primeiro lugar, do próprio texto, mas por igual da tradição literária e das poéticas mesopotâmicas.

se atribui a Sin-léqi-unnínni –, trabalho que procura beneficiar-se de tudo que, nos últimos anos, permitiu que se ampliasse nosso conhecimento, em primeiro lugar, do próprio texto, mas por igual da tradição literária e das poéticas mesopotâmicas.

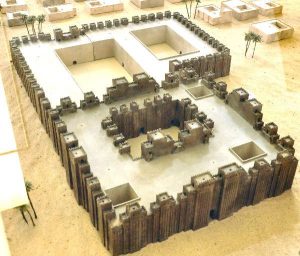

O que nele se narra é como Gilgámesh, o quinto rei de Úruk depois do dilúvio, passa por experiências existenciais marcantes que o levam a compreender os limites da natureza humana, os quais se impõem mesmo para alguém, como ele, filho de uma deusa e, por isso, dois terços divino e apenas um terço humano. É provável que ele tenha reinado de fato, por volta do século XXVII a.C., e que, em vista de seus grandes feitos, em especial a construção das muralhas de Úruk, se tenha desenvolvido em torno de seu nome as diversas narrativas heroicas que se conhecem a partir do século XXII a.C., inicialmente em sumério, em seguida em acádio. O texto que aqui se apresenta encontra-se no ápice do desenvolvimento desse ciclo heroico, devendo-se ao sábio Sin-léqi-unnínni a concatenação de tradições e narrativas anteriores num poema marcado por profunda reflexão antropológica.

De início, após louvar os feitos tradicionalmente atribuídos a Gilgámesh, na condição de alguém que repôs o que foi destruído pelo dilúvio, apresentam-se os seus excessos como rei – o desafio constante aos jovens de Úruk para disputas e o direito de dormir a primeira noite com as noivas (ele antes, o marido depois). Essa desmedida, que deixa clara quanto sua natureza é superior à do comum dos mortais, leva a que os habitantes da cidade se dirijam aos deuses em busca de uma solução. Como resposta, decidem eles criar um companheiro à altura de Gilgámesh, do que se encarrega a deusa Arúru, que o faz usando de argila. Assim surge Enkídu, uma espécie de personificação do homem primitivo, que vive desnudo junto dos animais, com eles comendo relva e bebendo água na cacimba. Inteirado da presença desse ser estranho na estepe, Gilgámesh encarrega uma prostituta sagrada, Shámhat, de ir até ele para que, com ela tendo relações sexuais, Enkídu seja atraído para a cidade. É assim que ele aprende a comer pão e beber cerveja, marcas da vida civilizada, sendo conduzido por Shámhat até a cidade de Úruk, onde enfrenta Gilgámesh no momento em que, dirigindo-se à câmara nupcial, o rei se prepara para exercer seu direito à primeira noite. Lutam os dois na rua, de um modo espetacular, o que serve para selar sua profunda amizade. Enfim, Gilgámesh encontrou um igual.

Os passos seguintes narram dois grandes feitos heroicos. O primeiro, o modo como Gilgámesh e Enkídu vencem Humbaba, o guardião da Floresta de Cedros (que se diz estar localizada no Líbano). Esse foi um feito intencionalmente buscado, em nome da fama, pois, sabem eles que “do homem os dias são contados, tudo que ele faça é vento”. Já a proeza seguinte é provocada pela deusa Ishtar – cuja esfera de atuação é tanto o sexo quanto a guerra: depois do regresso da Floresta de Cedros, apresentando-se Gilgámesh em sua glória de rei, atrai ele os olhos da deusa, que lhe propõe casamento. Ele a rechaça com extrema dureza, arrolando o destino infeliz de seus amantes, o que a leva a pedir a seu pai, o deus Ánu, que lhe entregue o Touro do Céu (isto é, a constelação do Touro), para que devaste Úruk. De novo os dois amigos enfrentam o perigo, vencendo e matando o Touro. A primeira metade do poema termina, assim, com a grande festa com que se comemora a vitória de Gilgámesh. Conforme se proclama, ele é o melhor dentre os moços, o mais ilustre dentre os varões!

A segunda parte principia de um modo lúgubre. Mesmo que o texto esteja muito fragmentado nessa passagem, pode-se saber que os deuses, reunidos em assembleia, determinam que, por haverem matado Humbaba e o Touro, um dos dois companheiros deve morrer, a escolha caindo sobre Enkídu. Abatido por grave doença, ele vem a falecer, provocando em Gilgámesh enorme dor, a qual se manifesta em prolongados lamentos. Depois de prestadas as honras fúnebres com toda pompa possível, Gilgámesh parte em viagem, em busca de Uta-napíshti, o herói que, tendo sobrevivido ao dilúvio por ter fabricado uma arca, conforme as instruções do deus Ea, foi também recompensado pelos deuses com o dom da imortalidade. O que atormenta Gilgámesh é a certeza de que, como Enkídu, seu destino é a morte. Conforme suas próprias palavras, mais de uma vez repetidas:

Como calar, como ficar eu em silêncio?

O amigo meu, que amo, tornou-se barro,

Enkídu, o amigo meu, que amo, tornou-se barro!

E eu: como ele não deitarei

E não mais levantarei de era em era?

Na rota até Uta-napíshti, Gilgámesh ultrapassa as fronteiras do mundo, indo além de onde nasce o sol, enfrentando perigos e tendo contato com seres extraordinários: os homens-escorpião, a taberneira Shidúri, o barqueiro Ur-shánabi, com quem cruza as águas da morte, e “os de pedra”, seres enigmáticos que ele destroça. Atingindo seu objetivo, Gilgámesh ouve de Uta-napíshti o relato do dilúvio e de como, na assembleia dos deuses, ao final, a ele e a sua esposa foi concedido o dom da imortalidade – com a observação de que isso aconteceu apenas uma vez, numa situação de todo extraordinária, não sendo de esperar que se repita com relação a nenhum outro homem.

Na rota até Uta-napíshti, Gilgámesh ultrapassa as fronteiras do mundo, indo além de onde nasce o sol, enfrentando perigos e tendo contato com seres extraordinários: os homens-escorpião, a taberneira Shidúri, o barqueiro Ur-shánabi, com quem cruza as águas da morte, e “os de pedra”, seres enigmáticos que ele destroça. Atingindo seu objetivo, Gilgámesh ouve de Uta-napíshti o relato do dilúvio e de como, na assembleia dos deuses, ao final, a ele e a sua esposa foi concedido o dom da imortalidade – com a observação de que isso aconteceu apenas uma vez, numa situação de todo extraordinária, não sendo de esperar que se repita com relação a nenhum outro homem.

Assim é que Gilgámesh deve voltar para a casa sem nada. A esposa de Uta-napíshti, contudo, intercede por ele, fazendo com que o marido lhe releve a localização da planta da juventude, no fundo das águas. Gilgámesh mergulha, traz consigo a planta, mas, ao parar junto de uma fonte para banhar-se, uma serpente a rouba, mudando imediatamente de pele. Nesse momento, Gilgámesh senta-se e chora, por considerar que fracassou em sua busca. A ação se fecha então como se abrira: com a descrição de Úruk e suas muralhas, sugerindo-se que aquilo que o herói traz consigo na volta não é algo material, mas sim a certeza de que a vida humana, ainda que breve, tem seu lugar no espaço de convivência com outros homens, configurado pela cidade. A glória de Gilgámesh é também a glória de Úruk e vice-versa.

A descoberta do poema

O texto de Sin-léqui-unnínni recebeu uma nova edição crítica, feita pelo assiriólogo inglês Andrew George e publicada em 2003, a qual levou em conta todos os manuscritos até então conhecidos. Isso significa, antes de tudo, que todas as traduções anteriores se encontram ultrapassadas, exigindo novas empreitadas, como a que aqui se apresenta ao leitor.

Mas mesmo depois disso outros dois importantes documentos foram dados à luz: o primeiro, um manuscrito descoberto na antiga Ugarit, no litoral da Síria, por Daniel Arnaud e por ele mesmo publicado em 2007, o qual permitiu completar de modo bastante significativo o prólogo do texto;o segundo, um novo testemunho da tabuinha 5, contendo grandes porções do texto antes só precariamente conhecidas ou mesmo de todo ignoradas foi identificado em 2011 por Farouk Al-Rawi, no Museu de Suleimaniyah, no Iraque, tendo sido publicado por ele próprio e por Andrew George em 2014. Depois da publicação dos textos de Ugarit e Suleimaniyah, a própria edição de 2003 deve ser posta em dia e, consequentemente, mais uma vez, as traduções.

Contudo, não se trata apenas de mudanças de ordem textual. O manuscrito de Ugarit, por exemplo, embaralha bastante o que se acreditava ser o poema em suas fases média e recente, já que, por exemplo, o prólogo geralmente atribuído a Sin-léqi-unnínni, a quem se acredita que se deve a última versão, revela-se agora anterior à época a ele tradicionalmente atribuída (séculos XIV-XIII a.C.). Pode-se dizer, num certo sentido, que cada novo dado tem como consequência ampliar nossos conhecimentos só para mostrar que a história do texto é sempre mais complexa do que se imaginava.

Essas circunstâncias decorrem do fato de que não só o poema que aqui se traduz como toda a matéria de Gilgámesh têm uma longuíssima história antiga e uma não mais que breve história contemporânea, separadas uma da outra por um vazio de praticamente vinte séculos. A história antiga estende-se, de um lado, por quase dois mil anos, desde cerca de 2100 a.C., em que se data o fragmento mais antigo, em sumério, do poema hoje conhecido como Bilgames e o touro do céu, procedente de Níppur, até o século II. a.C., quando foi escrita a última tabuinha conhecida de Ele que o abismo viu. A história contemporânea, por sua vez, tem início apenas em 1872 – ou seja, não soma ainda exíguos cento e cinquenta anos –, quando o assiriólogo inglês George Smith, em conferência na Society of Biblical Archaeology, em Londres, apresentou a narrativa do dilúvio que integra Ele que o abismo viu, lida por ele em tabuinha procedente da biblioteca de Assurbanípal, descoberta na metade do século XIX pela expedição conduzida por Henry Austen Layard na colina de Quyunjik, perto de Mossul, no Iraque, onde foi encontrado o “palácio sem igual” construído por Senaqueribe na antiga Nínive. Da biblioteca de Assurbanípal foram recuperadas mais de vinte mil tabuinhas ou fragmentos, depositadas hoje no Museu Britânico, que financiou a expedição arqueológica. Consta que, ao ler a tabuinha do dilúvio, George Smith, “homem ordinariamente reservado”, como um bom britânico, teria gritado: “Sou o primeiro a ler este texto após dois mil anos de esquecimento!”.

que breve história contemporânea, separadas uma da outra por um vazio de praticamente vinte séculos. A história antiga estende-se, de um lado, por quase dois mil anos, desde cerca de 2100 a.C., em que se data o fragmento mais antigo, em sumério, do poema hoje conhecido como Bilgames e o touro do céu, procedente de Níppur, até o século II. a.C., quando foi escrita a última tabuinha conhecida de Ele que o abismo viu. A história contemporânea, por sua vez, tem início apenas em 1872 – ou seja, não soma ainda exíguos cento e cinquenta anos –, quando o assiriólogo inglês George Smith, em conferência na Society of Biblical Archaeology, em Londres, apresentou a narrativa do dilúvio que integra Ele que o abismo viu, lida por ele em tabuinha procedente da biblioteca de Assurbanípal, descoberta na metade do século XIX pela expedição conduzida por Henry Austen Layard na colina de Quyunjik, perto de Mossul, no Iraque, onde foi encontrado o “palácio sem igual” construído por Senaqueribe na antiga Nínive. Da biblioteca de Assurbanípal foram recuperadas mais de vinte mil tabuinhas ou fragmentos, depositadas hoje no Museu Britânico, que financiou a expedição arqueológica. Consta que, ao ler a tabuinha do dilúvio, George Smith, “homem ordinariamente reservado”, como um bom britânico, teria gritado: “Sou o primeiro a ler este texto após dois mil anos de esquecimento!”.

Esse é um aspecto importante de nosso poema: faz pouco mais de um século que a matéria de Gilgámesh se introduziu no nosso cânone da literatura antiga, juntamente com outros poemas em sumério e acádio procedentes das civilizações mesopotâmicas. Trata-se de algo realmente extraordinário, que trouxe milênios esquecidos para o cômputo da história da humanidade – e o que é mais relevante: acrescentou ao corpus de suas tradições literárias um número considerável de textos cuja existência era antes, para nós, modernos, insuspeitada (Trecho da Introdução).

Uma versão do artigo que será publicado na revista Estudos Bíblicos em 2021 pode ser lida aqui.

Milhares de tabuinhas de barro com escrita cuneiforme foram recuperadas nas escavações arqueológicas da antiga Mesopotâmia. Algumas delas narram histórias de criação e dilúvio. Neste artigo vamos olhar mais de perto três dessas histórias: o Enuma Elish, a Epopeia de Gilgámesh e a Epopeia de Atrahasis. Algumas dessas histórias são chamadas hoje de cosmogonias.

criação e dilúvio. Neste artigo vamos olhar mais de perto três dessas histórias: o Enuma Elish, a Epopeia de Gilgámesh e a Epopeia de Atrahasis. Algumas dessas histórias são chamadas hoje de cosmogonias.

Saiba mais em Histórias do Antigo Oriente Médio: uma bibliografia e em Algumas observações sobre a reunião dos Biblistas Mineiros em 2017.

O Festival do Ano Novo na Babilônia herdou seu nome, Akitu, de um festival agrário sumério do III milênio a.C., o Akiti, celebrado na época da colheita e da semeadura da cevada.

Dois festivais do ano novo eram celebrados na cidade de Babilônia: um durante o primeiro mês do ano, Nisannu (março-abril), na primavera, e o outro durante o sétimo mês do ano, o Tashritu (setembro-outubro), no outono. São dois momentos importantes no calendário agrícola da Mesopotâmia: em Nisannu começavam as colheitas e em Tashritu os campos eram arados e semeados.

A duração do festival variava de cidade para cidade, obedecendo particularidades cultuais e sociais. A festa celebrada no mês de Nisannu é a melhor preservada em escritos recuperados da época helenística. Vamos ver como ela acontecia na cidade de Babilônia.

São 12 dias de festa.

No primeiro dia da festa, o primeiro dia do mês de Nisannu, ao amanhecer, o mubannû (oficial que organizava a mesa de oferendas) descia ao pátio de Marduk com uma chave. Com essa chave, o sacerdote abria o acesso a uma cisterna e jogava algo nela. Enquanto isso, animais para o sacrifício eram entregues no templo Akitu, e os deuses de fora da Babilônia se preparavam para viajar para a capital.

No segundo dia do mês de Nisannu o sumo sacerdote de Marduk (aḫu-rabû = irmão mais velho) levantava-se antes do nascer do sol, banhava-se no rio, dirigia-se ao templo do deus, o Eságil, retirava a cortina que cobria a estátua de Marduk e recitava uma oração. Depois abria as portas do templo e o pessoal do culto (ērib-bītis, os cantores e os sacerdotes das lamentações) entrava para realizar suas tarefas cotidianas. Enquanto isso, os principais deuses de Borsippa, Sippar e Uruk se preparavam com elaboradas cerimônias de vestimenta, o que indicava sua partida iminente no quinto dia.

No terceiro dia o sumo sacerdote recitava uma oração para Marduk e depois deixava entrar o resto do pessoal, tal como fizera no dia anterior. Algumas horas depois, um grupo de artesãos chega ao templo e o sumo sacerdote lhes dá pedras preciosas, ouro e madeira procedentes do tesouro de Marduk para que eles confeccionem estatuetas que serão utilizadas no sexto dia da festa.

No quarto dia, depois da purificação ritual no rio, o sumo sacerdote abria a cortina que protegia as estátuas de Marduk e de sua esposa Zarpanítum e recitava uma série de orações. Mais tarde neste dia o Enuma Elish era recitado do começo ao fim pelo sumo sacerdote. Enquanto isso, o rei se dirige de barco a Borsippa, onde está a estátua do deus Nabú, filho de Marduk. Ele a acompanhará até Babilônia.

No quinto dia o sumo sacerdote repete os rituais dos dias anteriores: purificação no rio, orações diante de Marduk e Zarpanítum e abertura das portas para entrada do pessoal do templo. Em seguida chega um exorcista que purifica o templo de Marduk com incenso e água procedente dos rios Tigre e Eufrates. Purifica também a capela de Nabú que fica dentro do templo de Marduk. Unge as portas da capela com resina de cedro, deposita um incensório no centro da capela e espalha ervas aromáticas. Em seguida, um açougueiro mata uma ovelha cortando-lhe a cabeça e o exorcista purifica o templo com o corpo de animal enquanto recita um exorcismo. Depois ele se dirige ao rio e atira o corpo do animal na água, o mesmo sendo feito pelo açougueiro com a cabeça da ovelha. Depois disto tanto o açougueiro quanto o exorcista abandonam a cidade até o final da festa. O sumo sacerdote cobre a capela de Nabú com um dossel dourado, faz uma oração a Marduk e prepara uma série de oferendas alimentícias. Na sequência o rei, que presumivelmente trouxe Nabú de Borsippa para Babilônia, é escoltado até o Eságil, onde o sumo sacerdote o priva de todos os símbolos do poder real – como o cetro, a cimitarra, o anel e a coroa, deixados diante de Marduk – e o leva diante de Marduk. Ali o sumo sacerdote, golpeia o rosto do rei, o puxa pela orelha até que ele se ajoelhe, ou seja, o coloca na posição de um acusado. Então o rei se declara inocente, dizendo que não negligenciou os deuses, a cidade de Babilônia, o templo de Marduk e nem seus súditos. Depois deste ritual de penitência, o sumo sacerdote, que recita uma oração e garante ao rei que Marduk ampliará o seu senhorio, exaltará seu reinado e destruirá seus inimigos, restitui-lhe os símbolos de poder. Mas, ainda uma vez, dá outro tapa no rosto do rei: se este chora, Marduk está satisfeito; se não chora, Marduk está irritado e seu reinado corre perigo. O dia termina com um sacrifício de um touro branco, feito pelo rei e pelo sumo sacerdote.

No sexto dia Nabú é levado ao templo Ehur-sagtila onde as cabeças das estatuetas fabricadas pelos artesãos, no terceiro dia da festa, são cortadas e estas são queimadas na presença de Nabú. Depois Nabú é levado para o templo de Marduk e é colocado diante de Marduk, em um altar chamado “Altar dos Destinos”.

Nada sabemos do que acontecia no sétimo dia.

No oitavo dia o sumo sacerdote aspergia o rei e o público com água “sagrada” e, em seguida, a estátua de Marduk e as estátuas das outras divindades saem em procissão, indo do Eságil até um templo situado fora da cidade, chamado Akitu. Não sabemos o que ocorria durante a procissão e que tipo de cerimônia se celebrava no templo Akitu. É possível que fosse uma comemoração da vitória de Marduk sobre Tiámat – veja-se o Enuma Elish – quando os deuses que acompanhavam Marduk lhe ofereciam presentes e comemoravam sua vitória.

Nada sabemos do nono dia.

No décimo dia Marduk e os deuses continuavam reunidos em assembleia no templo Akitu.

No décimo primeiro dia os deuses retornam em procissão para Babilônia e, dentro do Eságil se reúnem Marduk, Nabú e os outros deuses e ali determinam os destinos do ano vindouro. Em seguida Nabú volta para Borsippa e temos lacunas sobre o que ainda acontecia na festa, talvez ocorresse alguma cerimônia de casamento ritual entre Marduk e Zarpanítum.

No décimo segundo dia a festa terminava.

O Akitu é um ritual de forte conotação política, no qual o rei exerce função importante.

O ano novo celebra, na primavera, a renovação da natureza. Com a representação da vitória de Marduk sobre Tiámat, como narrado no Enuma Elish – que era recitado – a ordem cósmica fica assegurada sobre a possibilidade do caos, e a ordem política, garantida pelo rei que é fiel a Marduk, é legitimada. O ano que está começando será de prosperidade.

Trechos de algumas das fontes usadas

A declaração de inocência do rei e a resposta do sumo sacerdote, em tradução de COHEN, M. E. The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East. Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press, 1993, p. 447:

I have not sinned, Lord of all Lands! I have not neglected your divinity!

I have not caused the destruction of Babylon! I have not ordered its dissolution!

[I have not . . . ] the Esagil! I have not forgotten its rituals!

I have not struck the cheek of those under my protection!

. . . I have not belittled them!

[I have not . . . ] the walls of Babylon! I have not destroyed its outer fortications!

(break of approximately five lines)

[… the High Priest recites:] […]Have no fear …

… which Bel has uttered …

Bel [listens to] your prayer, …

He will glorify your dominion, …

He will exalt your kingship, …

On the day of the eshesh-festival…

Cleanse your hands at the Opening-of-the-Door, …

Day and night …

He, whose city is Babylon, …

Whose temple is the Esagil, …

The citizens of Babylon, those under his protection, …

Bel will bless you … forever!

He will destroy your enemy, smite your adversary!

Diz CARAMELO, F. O ritual de Akitu – O significado político e ideológico do Ano Novo na Mesopotâmia. Revista da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, n. 17, Lisboa, 2005, p. 160:

Em conclusão, podemos dizer que este festival constituía um ciclo ritual longo e complexo, apresentando duas dimensões complementares: uma privada e secreta e uma pública e colectiva. A primeira tinha lugar nos espaços reservados, como o templo ou a bit akiti, intervindo o rei e os sacerdotes; a segunda abrangia e envolvia a população da cidade, fazendo-a participar na renovação da ordem.

Dizem FELIU MATEU, L. ; MILLET ALBÀ, A. Enuma Elish y otros relatos babilónicos de la Creación. Madrid: Trotta, 2014, p. 34:

Esta fiesta del Año Nuevo de primavera de la Babilonia del primer milenio tenía, como el Enuma Elish, un trasfondo político e ideológico. Posiblemente, el rey de Babilonia representaba simbólicamente a Marduk en su victoria sobre Tiámat. De la misma manera, el rey asumía el compromiso de preeminencia de Babilonia por encima de sus enemigos. Todo el ritual se enmarca en un periodo de renacimiento político de Babilonia empezado por Nabucodonosor I. Es en este momento cuando —posiblemente— se compuso el Enuma Elish. El retrato que tenemos de la fiesta del Año Nuevo en Babilonia ya nos presenta el estadio final del proceso de entronización de Marduk, por un lado, y la inserción del Enuma Elish dentro de un acto ritual concreto, por otro. La revolución teológica ya se ha producido, la composición del Enuma Elish fue una pieza más y su inclusión dentro de la fiesta más importante del calendario cultual de Babilonia significó la culminación de esta reforma religiosa, desencadenada por un nuevo orden político que intentaba imponer a Babilonia por encima de sus vecinos. Hay que destacar que los símbolos de Anum y Enlil se cubrían durante la recitación del Enuma Elish a lo largo del cuarto día. Este acto es la visualización de las contradicciones teológicas que desencadenó esta reforma religiosa. Los dioses principales, tradicionales del panteón sumero-acadio, no pueden «escuchar» ni «contemplar» la entronización en lo más alto del panteón de un recién llegado como es Marduk.

Diz VAN DER TOORN, K. The Babylonian New Year Festival: New Insights from the Cuneiform Texts and their Bearing on Old Testament Study. In EMERTON, J. A. (ed.) Congress Volume Louven 1989 [Thirteenth Congress of the International Organization for the Study of the Old Testament]. Leiden: Brill, 1991, p. 334-335:

The political significance of the festival is evident, too, from a number of attendant observations. The divine approval of the king was proclaimed on 4, 8 and 11 Nisan, all public holidays. Documents from Southern Babylonia show that officials from outlying areas assisted at the ceremonies as well. This was the time when the king decided about any necessary changes in the administration. According to Assyrian evidence, treaties regulating the royal succession could be concluded on the same occasion. In connection with the festival, amnesty was granted to political prisoners, as Jehoiachin was to experience. Such events are usually connected with the accession to the throne; we know, however, that the installation of a new king might take place at any appropriate time of the year and did not need to be postponed to the beginning of the new year. The Nisan ceremonies are a divine ratification of the royal mandate, annually renewed. In view of its propagandistic effects, it is no wonder that kings attached great importance to the uninterrupted occurrence of the festival, especially in the first full year of their reign.

NOTIZIA, P. Review of BIDMEAD, J. The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia. 2. ed. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2004:

Il capitolo sulla storia degli studi relativi alla festività per l’akitu è esemplare di quanto siano state contrastanti le teorie elaborate a partire dall’inizio del secolo scorso. In principio gli studiosi si concentrarono sul valore teologico del rito (Langdon, Zimmern) che si supponeva celebrare la morte e la resurrezione del dio (e l’identificazione tra l’antico dio Tammuz/Dumuzi con Marduk) o la “magia” dello hieros-gamos che infondeva fertilità alla terra per un nuovo anno. In seguito studiosi come Hooke e Frankfort evidenziarono lo stretto rapporto che legava le pratiche rituali per la festività del Nuovo Anno e gli eventi narrati nel mito dell’Enuma eliå, composto verso la metà del secondo millennio, che descrive l’ascesa di Marduk a sovrano degli dei, l’ordinamento dell’universo e la creazione dell’uomo; arricchirono inoltre le tesi fino ad allora elaborate con concetti nuovi quali quello di “dramma cultuale” e sottolinearono l’importanza del combattimento rituale del dio (Marduk) che trionfa sul Caos (Tiamat) riportando l’ordine nel mondo e quella del sovrano che presiedeva alla processione lungo la Via Sacra. T. Jacobsen successivamente affermò che ad un antico akÎtu di natura agreste (valore fondativo) era stato affiancato il tema della “battaglia cultuale”, trasformandolo in un nuovo veicolo per trasmettere l’ideologia politica e sancire il potere di Babilonia. Lo storico delle religioni Eliade si è soffermato sul valore della ciclicità del tempo, della morte e della rinascita all’interno del rito, suggerendo che la lettura del mito cosmogonico (Enuma elish) servisse a rigenerare il tempo, e contribuisse alla ciclica rinascita del mondo. Gli studiosi più recenti hanno evidenziato il valore sociale e politico della celebrazione dell’akitu, riconoscendo (Van der Toorn) una serie di “riti di passaggio” che portavano al rinnovamento non cosmologico, ma dell’ordine religioso, politico e sociale della Babilonia, mentre Pongratz-Leisten ha analizzato la processione dell’akitu, dimostrando come esigenze politiche e cultuali diverse portassero a celebrazioni differenziate da luogo in luogo.

Fontes

BIDMEAD, J. The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia. 2. ed. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2014.

CARAMELO, F. O ritual de Akitu – O significado político e ideológico do Ano Novo na Mesopotâmia. Revista da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, n. 17, Lisboa, 2005, p. 157-160.

COHEN, M. E. The Cultic Calendars of the Ancient Near East. Bethesda, Maryland: CDL Press, 1993, p. 400-453.

DEBOURSE, C. Of Priests and Kings: The Babylonian New Year Festival in the Last Age of Cuneiform Culture. Leiden: Brill, 2022.

FELIU MATEU, L. ; MILLET ALBÀ, A. Enuma Elish y otros relatos babilónicos de la Creación. Madrid: Trotta, 2014, p. 31-35.

LINSSEN, M. J. H. The Cults of Uruk and Babylon: The Temple Ritual Texts as Evidence for Hellenistic Cult Practice. Leiden: Brill, 2004, p. 78-84.

PONGRATZ-LEISTEN, B. Festzeit und Raumverstandnis in Mesopotamien am Baispiel der akitu-Prozession. Kodikas / Code Ars Semeiotica, vol. 20, n. 1-2, Tübingen, 1997, p. 53-67.

SOMMER, B. The Babylonian Akitu Festival: Rectifying the King or Renewing the Cosmos? The Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society, vol. 27, 2000, p. 81-95.

VAN DER TOORN, K. The Babylonian New Year Festival: New Insights from the Cuneiform Texts and their Bearing on Old Testament Study. In EMERTON, J. A. (ed.) Congress Volume Louven 1989 [Thirteenth Congress of the International Organization for the Study of the Old Testament]. Leiden: Brill, 1991, p. 331-344.

Recursos online

Akitu Festival

Culture of defeat: the submission in written sources and the Archaeological record of the Ancient Near East

Cultura da derrota: a submissão segundo fontes escritas e registros arqueológicos do Antigo Oriente Médio

Seminário da Universidade Hebraica de Jerusalém e da Universidade de Viena: dias 22 e 23 de outubro de 2017. Na Universidade Hebraica de Jerusalém.

War and conquest figures prominently in all disciplines of ancient Near Eastern studies. They are usually reflected in textual sources as military campaigns and/or narratives of victory, and preserved in the archaeological record most commonly as destruction layers. In general, the successful agent in a conflict, his motivations, strategies and method is often the focus of the analysis.

To date, little attention has been given to the defeated party in conflicts. This can be ascribed both to a bias or ambivalence of both historical and archaeological records, where the response to defeat rarely constitutes the focus of the respective source, as well as to an intrinsically human preference to focus on ‘successful’ events, such as conquest, innovation, growth and expansion, thus reinforcing, or even skewing the historical account towards the successful party. However, the defeated entity often experiences a much more significant, often traumatic, and enduring impact. Different response mechanisms emerge, depending on the magnitude and type of defeat, and the cultural context in which this event is in embedded.

This workshop aims to focus on conflicts from the Late Bronze, the Iron Age Near East up to the Babylonian period, exploring (cultural) responses of defeated parties. Participants are asked to examine major sources of their field of expertise, such as the Biblical narrative, Assyrian administrative records, royal inscriptions and iconographic representations, as well as the archaeological record in light of accounts on conflict, focusing on the responses of the defeated party. This seminar intends shedding new light on the consequences and reactions to defeat and gaining a more nuanced and complete picture of conflicts. It further aims to initiate a more in-depth dialogue between interconnected disciplines, from Archaeology, Assyriology and Bible Studies, which far too often remain isolated.

Veja o livro.

Um artigo:

Sargon II, “King of the World”

By Josette Elayi – The Bible and Interpretation – September 2017

He believed he had been endowed by the gods with an exceptional intelligence, superior to that of the previous kings, including the famous Sargon of Akkad himself. He was convinced that his gods approved his policies. He was a king of justice and, therefore, his wars were just. He was a warlord, who personally led numerous military campaigns, but sometimes delegated the command of an expedition to one of his generals, contrary to what is written. It was natural decorum for him to describe the atrocities as normal episodes in battle descriptions. He used intimidation tactics, a kind of “psychological” warfare in the modern sense of the term: for example, to demoralize the inhabitants of the city that he wanted to conquer, he would display decapitated or flayed victims. He was highly effective in terms of military intelligence and strategy in his quest for victory.

O livro:

ELAYI, J. Sargon II, King of Assyria. Atlanta: SBL, 2017, 298 p. – ISBN 9781628371772 [gratuito no projeto ICI da SBL].

Among the most important questions addressed in the book are the following: what was his precise role in the disappearance of the kingdom of Israel? How did he succeed in enlarging the borders of the Assyrian Empire by several successful campaigns? How did he organize his empire (administration, trade, agriculture, libraries)?

Josette Elayi est une historienne de l’Antiquité, auteur de nombreux ouvrages dont une remarquable Histoire de la Phénicie (Perrin, 2013). Chercheuse et enseignante, elle a vécu de nombreuses années au Proche Orient.

Leia Mais:

Sargon II

E Marduk tornou-se Enlil

Andrea Seri observa no final de seu artigo The Role of Creation in Enuma Elish. Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, v. 12, 2012, p. 25-26:

Enuma Elish é um texto com várias camadas, composto com habilidade, de modo que pode ser lido em diferentes níveis. Em um nível básico, o enredo contém todos os ingredientes de uma história de sucesso: uma teogonia, uma batalha épica impressionante com magias, monstros, criaturas impiedosas, um deus heroico, a criação do universo, bem como a etiologia da cidade de Babilônia e do templo principal de Marduk, o Eságil. A combinação de motivos épicos e religiosos com alusões claras a outros temas literários facilmente reconhecíveis parece ter estabelecido o tom dramático certo para a recitação ou a promulgação da história durante o Festival do Ano Novo na Babilônia [Akitu]. Em nível textual, Enuma Elish também é uma exibição de erudição dos escribas, porque inclui trocadilhos, etimologias literárias, empréstimos diretos e alusões a vários gêneros e tópicos da tradição mitológica e literária mesopotâmica.

As sete tabuinhas do Enuma Elish contêm várias criações que servem a diferentes propósitos e que são introduzidas progressivamente ao longo do texto. Inicialmente, a reprodução biológica traz à existência os personagens principais na forma de uma geração de deuses que preparam o palco para o nascimento de Marduk. A criação biológica é interrompida quando ocorre o primeiro assassinato e Ea constrói seu santuário sobre o cadáver de Apsu. Este episódio apresenta a destruição como um meio de criação, e também inicia uma série de eventos que apresentam tensão recorrente entre criações biológicas e artificiais e entre destruição e criação. Certamente não é por acaso que foi Ea quem realizou a primeira criação artificial, porque ele é conhecido na tradição mesopotâmica por sua engenhosidade. Nisto Marduk segue os passos de seu pai, e na preparação para a batalha, ele modela artefatos (o arco e a rede), enquanto Tiámat produz onze seres terríveis. As criações de Marduk mostram que enquanto Tiámat gera criaturas vivas, ele fabrica instrumentos poderosos. Como Ea tinha feito antes dele, Marduk cria o mundo matando Tiámat e usando seu corpo como matéria-prima. A narrativa da criação de diferentes níveis do universo é engenhosamente equiparada à criação de santuários cósmicos para as três principais divindades tradicionais do panteão babilônico: Anu, Enlil e Ea. O último ato criativo de Marduk consiste em modelar ornamentos com as onze criaturas de Tiámat para decorar os portões da habitação de seu pai Ea no Apsu. Então ocorre a segunda criação de Ea, a da humanidade, mas, nesse caso, a ideia não é dele. É de Marduk. Mais uma vez, uma criatura viva, Qingu neste caso, é sacrificada para criar. Isso fecha o círculo: no início, Ea cria sua morada cósmica depois de matar Apsu, e, quase no final, ele modela a humanidade depois que Qingu é imolado. Finalmente, os planos de Marduk e a construção de Babilônia e do Eságil implica a sua apropriação da esfera cósmica antes pertencente a Enlil.

A seção cosmogônica do Enuma Elish é central porque permite a Marduk ter o controle total do que ele criou, mas também porque representa o ápice da ascensão de Marduk. Na verdade, depois que ele cria a Terra, Marduk se torna um deus fisicamente inativo, pois ele agora dá ideias que outros realizam. A capacidade de criar proporcionou-lhe o tipo de maturidade dos reis que governam sabiamente do conforto de seus palácios, enquanto seus subordinados executam seus planos. As várias criações que aparecem ao longo da história – especialmente a do universo – incorporam temas literários já existentes. Mas empréstimos e alusões são quase sempre modificados para se adequar à exaltação de Marduk. Por exemplo, a separação do céu e da terra, geralmente atribuída a Enlil, agora é realizada por Marduk. O poeta ousa tanto que faz Marduk criar a morada cósmica de Enlil para, em seguida, dela se apropriar. Embora existam histórias independentes do Mundo Inferior (por exemplo, A Ascensão de Ishtar; Nergal e Ereshkigal; Gilgámesh, Enkidu e o Mundo Inferior), ele não é mencionado no Enuma Elish. Em vez disso, é substituído pela proeminente posição dada ao Apsu, o santuário do pai de Marduk e o lugar onde Marduk nasceu. A criação do universo no Enuma Elish é peculiar. A sua inserção no lugar que ocupa na composição é estratégica, pois permite que Marduk se torne Enlil.

Enūma eliš is a multilayered and skillfully composed text that can be read at different levels. At the basic register, the plot contains all the ingredients of a successful story: a theogony, an awesome epic battle with spells, monsters, merciless creatures, a heroic god, the creation of the universe, as well as the aetiology of the city of Babylon and of Marduk’s main temple, Esaĝila. The combination of epic and religious motives with clear allusions to other, easily recognizable, literary themes seems to have set the right dramatic tone for the recitation or the enactment of the story during the New Year Festival in Babylon (see, e.g., Çarğirgan and Lambert 1991–3: 91; Toorn 1991; Bidmead 2002: 66–76). At the textual level Enūma eliš is also a display of scribal erudition because it includes puns, literary etymologies, direct borrowings and allusions to various genres and topics of the Mesopotamian mythological and literary tradition.

The seven tablets of Enūma eliš contain various creations that serve different purposes and that are introduced progressively throughout the text. Initially biological reproduction brings the dramatis personae into existence in the manner of a generation of gods that set the stage for the birth of Marduk. Biological creation is interrupted when the first slaying occurs and Ea builds his shrine upon Apsû’s corpse. This episode introduces destruction as a means of creation, and it also initiates a series of events that show recurrent tension between biological and artificial creations and between destruction and creation. It is certainly not by chance that it was Ea who brought about the first artificial creation, because he is notorious in Mesopotamian tradition for his ingenious ways. In this, Marduk follows in the footsteps of his father, and in preparation for the battle he fashions artifacts (the bow and the net); while Tiʾamat produces eleven fearsome beings. Marduk’s creations show that whereas Tiʾamat generates living creatures, he manufactures powerful instruments. As Ea had done before him, Marduk creMarduk e seu dragão Mušḫuššuates the world by killing Tiʾamat and by using her body as the raw material. The narrative of the creation of different levels of the universe is ingeniously equated with the creation of cosmic shrines for the three traditional main deities of the Babylonian pantheon: Anu, Enlil, and Ea (see Ragavan 2010: 108–110). Marduk’s last creative act consists of modeling ornaments out of Tiʾamat’s eleven creatures to decorate the gates of his father’s dwelling, the Apsû. Then follows Ea’s second creation, that of mankind, but in this case the idea is not his. It is Marduk’s. Once again, a living creature, Qingu in this case, is sacrificed in order to create. This ties the circle neatly: at the beginning Ea creates his cosmic abode after killing Apsû, and towards the end he fashions mankind after Qingu is immolated. Finally, Marduk’s plans and the building of Babylon and Esaĝila imply his appropriation of Enlil’s cosmic sphere.

The cosmogony section of Enūma eliš is central because it enables Marduk to have full control of what he created, but also because it represents the zenith in Marduk’s ascent. Indeed, after he creates the Earth, Marduk becomes a physically inactive god, for he now gives ideas that others carry out. The ability to create provided him with the kind of maturity of those kings who rule wisely from the comfort of the palace while their subordinates set plans in motion. The various creations that appear throughout the story—and that of the universe in particular—incorporate already existing literary themes. But borrowings and allusions are almost always twisted to suit Marduk’s exaltation. For example, the separation of Heaven and Earth, usually attributed to Enlil, is now performed by Marduk. The poet goes so far as to have Marduk create Enlil’s cosmic abode and take it away from him. Although there are independent stories about the Netherworld (e.g., Ištar’s Descent; Nergal and Ereškigal; and Gilgameš, Enkidu and the Netherworld), the Underworld is not even mentioned in Enūma eliš. It is instead replaced by the prominent position given to Apsû, the shrine of Marduk’s father and the place where Marduk was born. The creation of the universe in Enūma eliš is idiosyncratic. Its insertion in the place it occupies in relation to the entire composition is strategic, for it enables Marduk to become Enlil.