E Marduk tornou-se Enlil

Andrea Seri observa no final de seu artigo The Role of Creation in Enuma Elish. Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, v. 12, 2012, p. 25-26:

Enuma Elish é um texto com várias camadas, composto com habilidade, de modo que pode ser lido em diferentes níveis. Em um nível básico, o enredo contém todos os ingredientes de uma história de sucesso: uma teogonia, uma batalha épica impressionante com magias, monstros, criaturas impiedosas, um deus heroico, a criação do universo, bem como a etiologia da cidade de Babilônia e do templo principal de Marduk, o Eságil. A combinação de motivos épicos e religiosos com alusões claras a outros temas literários facilmente reconhecíveis parece ter estabelecido o tom dramático certo para a recitação ou a promulgação da história durante o Festival do Ano Novo na Babilônia [Akitu]. Em nível textual, Enuma Elish também é uma exibição de erudição dos escribas, porque inclui trocadilhos, etimologias literárias, empréstimos diretos e alusões a vários gêneros e tópicos da tradição mitológica e literária mesopotâmica.

As sete tabuinhas do Enuma Elish contêm várias criações que servem a diferentes propósitos e que são introduzidas progressivamente ao longo do texto. Inicialmente, a reprodução biológica traz à existência os personagens principais na forma de uma geração de deuses que preparam o palco para o nascimento de Marduk. A criação biológica é interrompida quando ocorre o primeiro assassinato e Ea constrói seu santuário sobre o cadáver de Apsu. Este episódio apresenta a destruição como um meio de criação, e também inicia uma série de eventos que apresentam tensão recorrente entre criações biológicas e artificiais e entre destruição e criação. Certamente não é por acaso que foi Ea quem realizou a primeira criação artificial, porque ele é conhecido na tradição mesopotâmica por sua engenhosidade. Nisto Marduk segue os passos de seu pai, e na preparação para a batalha, ele modela artefatos (o arco e a rede), enquanto Tiámat produz onze seres terríveis. As criações de Marduk mostram que enquanto Tiámat gera criaturas vivas, ele fabrica instrumentos poderosos. Como Ea tinha feito antes dele, Marduk cria o mundo matando Tiámat e usando seu corpo como matéria-prima. A narrativa da criação de diferentes níveis do universo é engenhosamente equiparada à criação de santuários cósmicos para as três principais divindades tradicionais do panteão babilônico: Anu, Enlil e Ea. O último ato criativo de Marduk consiste em modelar ornamentos com as onze criaturas de Tiámat para decorar os portões da habitação de seu pai Ea no Apsu. Então ocorre a segunda criação de Ea, a da humanidade, mas, nesse caso, a ideia não é dele. É de Marduk. Mais uma vez, uma criatura viva, Qingu neste caso, é sacrificada para criar. Isso fecha o círculo: no início, Ea cria sua morada cósmica depois de matar Apsu, e, quase no final, ele modela a humanidade depois que Qingu é imolado. Finalmente, os planos de Marduk e a construção de Babilônia e do Eságil implica a sua apropriação da esfera cósmica antes pertencente a Enlil.

A seção cosmogônica do Enuma Elish é central porque permite a Marduk ter o controle total do que ele criou, mas também porque representa o ápice da ascensão de Marduk. Na verdade, depois que ele cria a Terra, Marduk se torna um deus fisicamente inativo, pois ele agora dá ideias que outros realizam. A capacidade de criar proporcionou-lhe o tipo de maturidade dos reis que governam sabiamente do conforto de seus palácios, enquanto seus subordinados executam seus planos. As várias criações que aparecem ao longo da história – especialmente a do universo – incorporam temas literários já existentes. Mas empréstimos e alusões são quase sempre modificados para se adequar à exaltação de Marduk. Por exemplo, a separação do céu e da terra, geralmente atribuída a Enlil, agora é realizada por Marduk. O poeta ousa tanto que faz Marduk criar a morada cósmica de Enlil para, em seguida, dela se apropriar. Embora existam histórias independentes do Mundo Inferior (por exemplo, A Ascensão de Ishtar; Nergal e Ereshkigal; Gilgámesh, Enkidu e o Mundo Inferior), ele não é mencionado no Enuma Elish. Em vez disso, é substituído pela proeminente posição dada ao Apsu, o santuário do pai de Marduk e o lugar onde Marduk nasceu. A criação do universo no Enuma Elish é peculiar. A sua inserção no lugar que ocupa na composição é estratégica, pois permite que Marduk se torne Enlil.

Enūma eliš is a multilayered and skillfully composed text that can be read at different levels. At the basic register, the plot contains all the ingredients of a successful story: a theogony, an awesome epic battle with spells, monsters, merciless creatures, a heroic god, the creation of the universe, as well as the aetiology of the city of Babylon and of Marduk’s main temple, Esaĝila. The combination of epic and religious motives with clear allusions to other, easily recognizable, literary themes seems to have set the right dramatic tone for the recitation or the enactment of the story during the New Year Festival in Babylon (see, e.g., Çarğirgan and Lambert 1991–3: 91; Toorn 1991; Bidmead 2002: 66–76). At the textual level Enūma eliš is also a display of scribal erudition because it includes puns, literary etymologies, direct borrowings and allusions to various genres and topics of the Mesopotamian mythological and literary tradition.

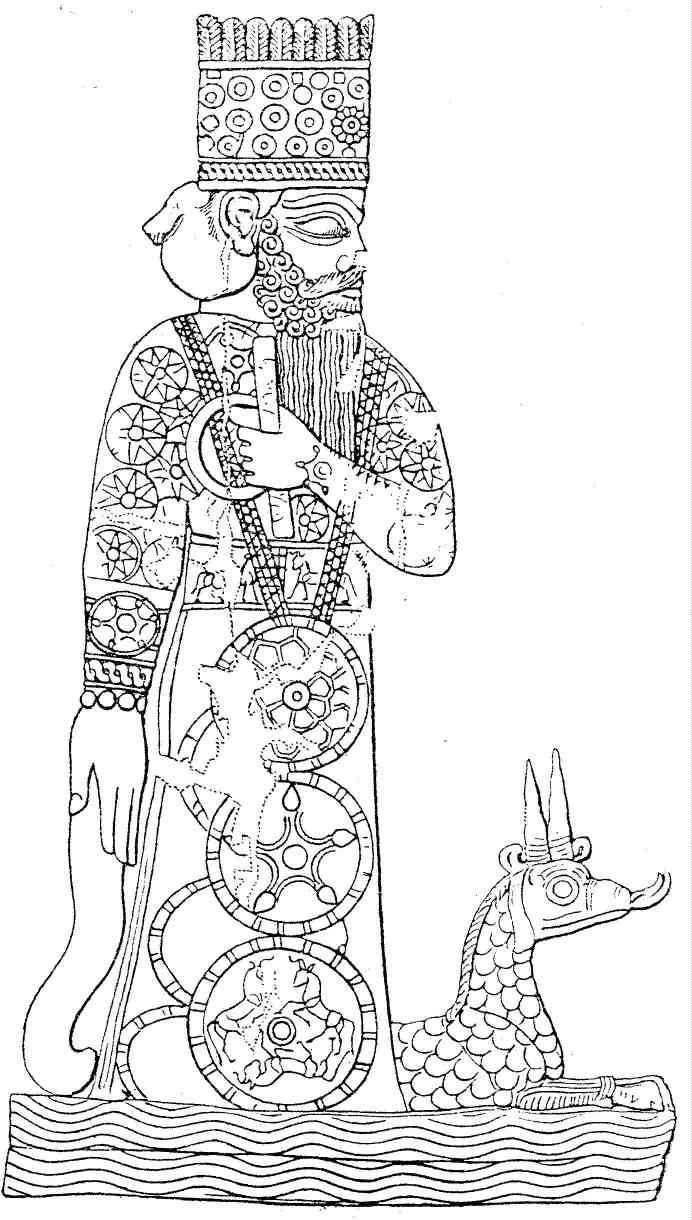

The seven tablets of Enūma eliš contain various creations that serve different purposes and that are introduced progressively throughout the text. Initially biological reproduction brings the dramatis personae into existence in the manner of a generation of gods that set the stage for the birth of Marduk. Biological creation is interrupted when the first slaying occurs and Ea builds his shrine upon Apsû’s corpse. This episode introduces destruction as a means of creation, and it also initiates a series of events that show recurrent tension between biological and artificial creations and between destruction and creation. It is certainly not by chance that it was Ea who brought about the first artificial creation, because he is notorious in Mesopotamian tradition for his ingenious ways. In this, Marduk follows in the footsteps of his father, and in preparation for the battle he fashions artifacts (the bow and the net); while Tiʾamat produces eleven fearsome beings. Marduk’s creations show that whereas Tiʾamat generates living creatures, he manufactures powerful instruments. As Ea had done before him, Marduk creMarduk e seu dragão Mušḫuššuates the world by killing Tiʾamat and by using her body as the raw material. The narrative of the creation of different levels of the universe is ingeniously equated with the creation of cosmic shrines for the three traditional main deities of the Babylonian pantheon: Anu, Enlil, and Ea (see Ragavan 2010: 108–110). Marduk’s last creative act consists of modeling ornaments out of Tiʾamat’s eleven creatures to decorate the gates of his father’s dwelling, the Apsû. Then follows Ea’s second creation, that of mankind, but in this case the idea is not his. It is Marduk’s. Once again, a living creature, Qingu in this case, is sacrificed in order to create. This ties the circle neatly: at the beginning Ea creates his cosmic abode after killing Apsû, and towards the end he fashions mankind after Qingu is immolated. Finally, Marduk’s plans and the building of Babylon and Esaĝila imply his appropriation of Enlil’s cosmic sphere.

The cosmogony section of Enūma eliš is central because it enables Marduk to have full control of what he created, but also because it represents the zenith in Marduk’s ascent. Indeed, after he creates the Earth, Marduk becomes a physically inactive god, for he now gives ideas that others carry out. The ability to create provided him with the kind of maturity of those kings who rule wisely from the comfort of the palace while their subordinates set plans in motion. The various creations that appear throughout the story—and that of the universe in particular—incorporate already existing literary themes. But borrowings and allusions are almost always twisted to suit Marduk’s exaltation. For example, the separation of Heaven and Earth, usually attributed to Enlil, is now performed by Marduk. The poet goes so far as to have Marduk create Enlil’s cosmic abode and take it away from him. Although there are independent stories about the Netherworld (e.g., Ištar’s Descent; Nergal and Ereškigal; and Gilgameš, Enkidu and the Netherworld), the Underworld is not even mentioned in Enūma eliš. It is instead replaced by the prominent position given to Apsû, the shrine of Marduk’s father and the place where Marduk was born. The creation of the universe in Enūma eliš is idiosyncratic. Its insertion in the place it occupies in relation to the entire composition is strategic, for it enables Marduk to become Enlil.