Esta é uma tradução do capítulo 4 de CLINE, E. H. Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sites. Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses, 2016. O título do capítulo é Early Archaeology in Mesopotamia. O texto original em inglês é transcrito, no final, na íntegra.

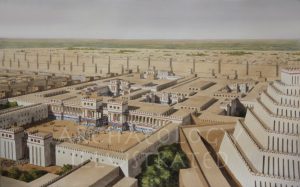

O local da antiga cidade de Ur está situado às margens do rio Eufrates, no atual Iraque, ao norte de onde o rio deságua no Golfo Pérsico. Esta é a região conhecida como antiga Mesopotâmia, nome que significa “entre os rios” – isto é, o Tigre e o Eufrates. Ur era um local famoso na antiguidade, com todas as características típicas de uma cidade mesopotâmica da Idade do Bronze, incluindo estruturas religiosas conhecidas como zigurates. A partir de 1922, o local foi escavado por Sir Leonard Woolley e seu braço direito, Max Mallowan. Mas foi só na quinta temporada de campo, em 1926-1927, que começaram a escavar o cemitério no local – os famosos Poços da Morte de Ur, que chamaram a atenção da Europa.

antiga Mesopotâmia, nome que significa “entre os rios” – isto é, o Tigre e o Eufrates. Ur era um local famoso na antiguidade, com todas as características típicas de uma cidade mesopotâmica da Idade do Bronze, incluindo estruturas religiosas conhecidas como zigurates. A partir de 1922, o local foi escavado por Sir Leonard Woolley e seu braço direito, Max Mallowan. Mas foi só na quinta temporada de campo, em 1926-1927, que começaram a escavar o cemitério no local – os famosos Poços da Morte de Ur, que chamaram a atenção da Europa.

Cemitério real de Ur

:. Entre 1927 e 1929, Sir Leonard Woolley e Max Mallowan descobriram 16 sepulturas reais em Ur. Os enterros reais datam de cerca de 2500 a.C. e eram bastante impressionantes em comparação com muitos outros túmulos encontrados no cemitério de Ur. Cada tumba geralmente tinha uma câmara de pedra, abobadada ou em forma de cúpula, onde o corpo real era colocado. A câmara ficava no fundo de um poço profundo, cujo acesso só era possível através de uma rampa íngreme vinda da superfície. Bens preciosos foram encontrados principalmente na câmara mortuária com o corpo, enquanto veículos com rodas, bois e servidores foram encontrados tanto na câmara quanto na cova externa.

:. Numerosos servidores foram encontrados nos Poços da Morte: uma tumba tinha mais de 70 corpos que foram com seu senhor ou senhora para a vida após a morte. A maioria eram mulheres, mas os homens também estavam presentes. Woolley presumiu que eles haviam bebido veneno depois de descerem a rampa até o poço, mas tomografias computadorizadas de alguns dos crânios feitas em 2009 indicam que pelo menos algumas dessas pessoas foram mortas por terem um instrumento afiado enfiado em suas cabeças logo abaixo e atrás da orelha. A morte teria sido instantânea.

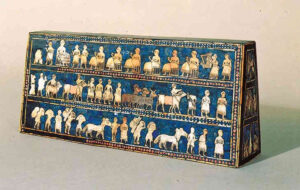

:. Os bens funerários que Woolley e Mallowan encontraram com os corpos reais eram surpreendentes, apesar do fato de muitos túmulos terem sido saqueados na antiguidade. Entre os achados estavam tiaras de ouro, joias de ouro e lápis-lazúli, adagas de ouro e eletro e um capacete de ouro. Havia também esculturas delicadas, os restos de uma harpa de madeira com incrustações de marfim e lápis-lazúli e uma caixa de madeira com incrustações que Woolley chamou de Estandarte de Ur.

antiguidade. Entre os achados estavam tiaras de ouro, joias de ouro e lápis-lazúli, adagas de ouro e eletro e um capacete de ouro. Havia também esculturas delicadas, os restos de uma harpa de madeira com incrustações de marfim e lápis-lazúli e uma caixa de madeira com incrustações que Woolley chamou de Estandarte de Ur.

Henry Rawlinson e Paul-Émile Botta

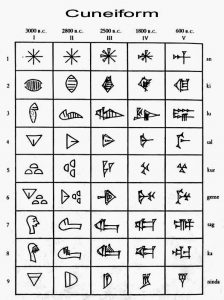

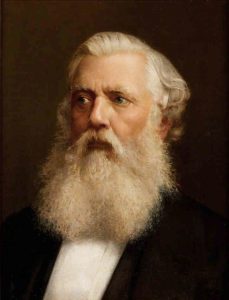

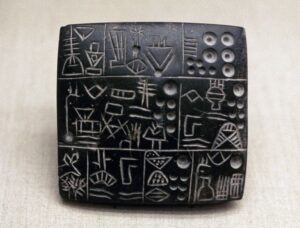

:. Entre os primeiros estudiosos e arqueólogos modernos que trabalharam na Mesopotâmia estava Sir Henry Rawlinson, que ajudou a decifrar e traduzir a escrita cuneiforme na década de 1830. Cuneiforme é um sistema de escrita em forma de cunha usado para escrever acádio, babilônico, hitita, persa antigo e outras línguas no  antigo Oriente Médio.

antigo Oriente Médio.

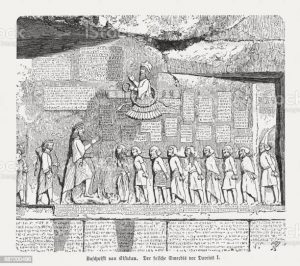

. Rawlinson, que era um oficial do exército britânico destacado no que hoje é o Irã, desvendou o segredo do cuneiforme traduzindo uma inscrição trilíngue escrita em persa antigo, elamita e babilônico. Dario, o Grande, da Pérsia, havia esculpido a inscrição 120 metros acima do solo do deserto, na face de um penhasco no local de Behistun, por volta de 519 a.C.

. Em 1837, cerca de 10 anos antes de a cópia de toda a inscrição ser concluída, Rawlinson descobriu como ler os dois primeiros parágrafos da parte escrita em persa antigo. Segundo consta, ele levou mais 20 anos para decifrar as partes babilônicas e elamitas da inscrição e ler tudo com sucesso*.

. Ao longo do caminho, porém, Rawlinson conseguiu usar seu conhecimento de cuneiforme para começar a traduzir algumas das inscrições que o arqueólogo britânico Sir Austen Henry Layard estava encontrando em suas escavações no que hoje é o Iraque. Na verdade, Rawlinson conseguiu confirmar que Layard havia encontrado dois locais antigos que, até então, eram conhecidos apenas pela Bíblia.

* O autor não menciona, mas Edward Hincks foi tão importante na decifração do cuneiforme quanto Rawlinson. Cf. sobre isso Leituras sobre a decifração da escrita cuneiforme, post publicado no Observatório Bíblico em 15.03.2025.

:. Paul-Émile Botta foi um arqueólogo nascido na Itália que trabalhou para os franceses. Em dezembro de 1842, ele iniciou as primeiras escavações arqueológicas já realizadas no que hoje é o Iraque. Os primeiros esforços de Botta concentraram-se nos montes conhecidos como Kuyunjik, que ficam do outro lado do rio da cidade de Mossul. No entanto, ele não encontrou muita coisa lá e rapidamente abandonou seus esforços.

. Por meio de um de seus trabalhadores, Botta soube que algumas esculturas foram encontradas em um local chamado Khorsabad, localizado a cerca de 22 quilômetros ao norte. Em março de 1843, ele começou a escavar ali e, em uma semana, começou a desenterrar um grande palácio assírio.

. A princípio, Botta pensou ter encontrado os restos da antiga Nínive, mas agora sabemos que Khorsabad é o antigo local de Dur Sharrukin, a capital do rei neoassírio Sargão II (721–705 a.C.) .

Austen Henry Layard

:. A partir de 1845, Sir Austen Henry Layard empreendeu seus esforços arqueológicos iniciais em Nimrud, que ele inicialmente pensou ser a antiga Nínive. Surpreendentemente, no primeiro dia de escavação, a sua equipe de seis homens locais encontrou não um, mas dois palácios assírios! Hoje, eles são geralmente chamados de Palácios do Noroeste e do Sudoeste.

chamados de Palácios do Noroeste e do Sudoeste.

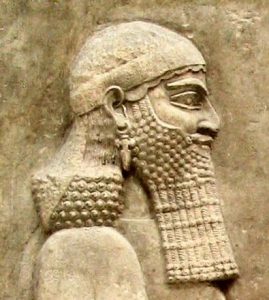

. A partir das inscrições encontradas por Layard, eventualmente ficou claro que o Palácio Noroeste foi construído por Assurnasirpal II (884–859 a.C.), e o Palácio Sudoeste foi construído por Esarhaddon (680–669 a.C.). Mais tarde, um Palácio Central foi descoberto no local, construído por Tiglat-Pileser III (745–727 a.C.). Salmanasar III (858–824 a.C.) também mandou construir edifícios e monumentos no local.

. Layard publicou um livro sobre suas incríveis descobertas em Nimrud. O livro se chamava Nineveh and Its Remains, mas quando as inscrições do local foram finalmente decifradas, eles confirmaram que na verdade era a antiga Kalhu (Calá bíblica), em vez de Nínive.

. Acontece que Kalhu foi a segunda capital construída pelos assírios, sendo a primeira a própria Assur. Serviu como capital por quase 175 anos, de 879 a 706 a.C. Depois disso, Sargão II mudou a capital para Dur Sharrukin por um breve período, e então Senaquerib mudou-a para Nínive.

. Acontece que Kalhu foi a segunda capital construída pelos assírios, sendo a primeira a própria Assur. Serviu como capital por quase 175 anos, de 879 a 706 a.C. Depois disso, Sargão II mudou a capital para Dur Sharrukin por um breve período, e então Senaquerib mudou-a para Nínive.

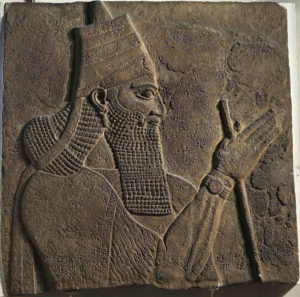

:. Em 1849, Layard retornou a Mossul para outra rodada de escavações, mas desta vez, seu foco principal foi Kuyunjik, o monte que Botta havia abandonado sete anos antes. Os homens de Layard começaram imediatamente a desenterrar paredes com relevos e imagens, e a tradução das tabuinhas ali encontradas confirmou que este era o verdadeiro local da antiga Nínive. Quando Layard e várias outras escavadores terminaram, um palácio de Senaquerib (705–681 a.C.) havia sido descoberto, bem como um palácio de Assurbanípal, neto de Senaquerib (668–627 a.C.).

. Senaquerib, que transferiu a capital assíria de Dur Sharrukin depois de subir ao trono, construiu o que chamou de Palácio sem Rival, em Nínive. Hoje, o palácio é provavelmente mais famoso pela Sala de Laquis. Aqui, Layard encontrou relevos de parede mostrando a captura da cidade de Laquis por Senaquerib em 701 a.C. Naquela época, Laquis era a segunda cidade mais poderosa de Judá. Senaquerib atacou-a antes de sitiar Jerusalém.

. Senaquerib, que transferiu a capital assíria de Dur Sharrukin depois de subir ao trono, construiu o que chamou de Palácio sem Rival, em Nínive. Hoje, o palácio é provavelmente mais famoso pela Sala de Laquis. Aqui, Layard encontrou relevos de parede mostrando a captura da cidade de Laquis por Senaquerib em 701 a.C. Naquela época, Laquis era a segunda cidade mais poderosa de Judá. Senaquerib atacou-a antes de sitiar Jerusalém.

. A captura de Laquis é descrita na Bíblia Hebraica, assim como o cerco de Jerusalém. A descoberta de Layard foi uma das primeiras vezes em que um evento da Bíblia pôde ser confirmado por fontes extrabíblicas.

. Escavações do século XX no local de Laquis, onde hoje é Israel, não apenas confirmaram a destruição da cidade por volta de 701 a.C. mas também revelaram uma rampa de cerco assíria, construída com toneladas de terra e rochas e semelhante às rampas retratadas nos relevos de Senaquerib.

. Os relevos de Nínive estão cheios de cenas horríveis, incluindo prisioneiros tendo suas línguas arrancadas e sendo esfolados vivos, junto com cabeças decapitadas exibidas em um poste. É universalmente aceite que os assírios realmente cometeram tais atrocidades, mas a representação deles no palácio de Senaquerib é provavelmente entendida como propaganda – um meio de dissuadir outros reinos de se rebelarem.

:. É importante notar que Layard não era um arqueólogo treinado. Ele frequentemente deixava o meio das salas sem escavar e não estava particularmente interessado em nenhuma cerâmica que seus homens descobriam. Ele estava, no entanto, interessado nos painéis inscritos que compunham as paredes das salas, bem como nas estátuas colossais. Muitos deles foram enviados para o Museu Britânico, onde podem ser vistos hoje.

Escavações continuadas

:. Em 1853, Hormuzd Rassam, protegido e sucessor de Layard em Nínive, descobriu o palácio de Assurbanípal, literalmente debaixo do nariz do sucessor de Botta, Victor Place, que estava cavando no mesmo local.

. Rassam e seus homens cavaram secretamente por três noites seguidas no território disputado no monte. Quando suas trincheiras revelaram pela primeira vez as paredes e esculturas do palácio, Place não pôde fazer nada além de parabenizá-los por suas descobertas.

paredes e esculturas do palácio, Place não pôde fazer nada além de parabenizá-los por suas descobertas.

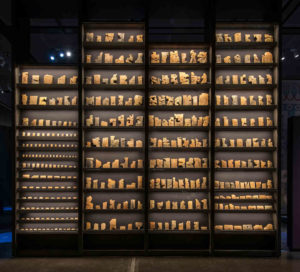

. Dentro do palácio, Rassam encontrou uma enorme biblioteca de textos cuneiformes, assim como Layard havia feito anteriormente no palácio de Senaquerib. Na verdade, é geralmente considerado que os arquivos do Estado estavam divididos entre os dois palácios, apesar de estarem separados por duas gerações. Além de documentos estatais, Rassam encontrou textos religiosos, científicos e literários, incluindo cópias da Epopeia de Gilgámesh e da história do dilúvio na Babilônia.

:. Em 1872, quase 20 anos depois de Rassam ter encontrado as tabuinhas pela primeira vez, um homem chamado George Smith trabalhava no Museu Britânico, separando as tabuinhas que Rassam havia enviado de Nínive.

. A certa altura, Smith descobriu um grande fragmento que relatava um grande dilúvio, semelhante ao relato do dilúvio encontrado na Bíblia Hebraica. Quando Smith anunciou sua descoberta em uma reunião da Sociedade de Arqueologia Bíblica em dezembro de 1872, Londres inteira ficou alvoroçada.

. O problema, porém, era que faltava um pedaço grande no meio da tabuinha. Foi prometida uma recompensa a quem procurasse o fragmento desaparecido, e o próprio Smith decidiu aceitar o desafio, embora nunca tivesse estado na Mesopotâmia e não tivesse formação como arqueólogo.

. Surpreendentemente, apenas cinco dias depois de chegar a Nínive, Smith encontrou a peça que faltava pesquisando na pilha de terra das escavações anteriores. Ele também encontrou cerca de 300 outras peças de tabuinhas de argila que os trabalhadores haviam descartado.

. Surpreendentemente, apenas cinco dias depois de chegar a Nínive, Smith encontrou a peça que faltava pesquisando na pilha de terra das escavações anteriores. Ele também encontrou cerca de 300 outras peças de tabuinhas de argila que os trabalhadores haviam descartado.

:. As escavações do século XIX em Nimrud, Nínive, Khorsabad, Ur, Babilônia e outros locais deram início a uma era de escavações na região que continua até hoje. Ainda em 1988, descobertas espetaculares foram feitas em Nimrud por arqueólogos iraquianos locais. Eles descobriram os túmulos de várias princesas assírias da época de Assurnasirpal II, do século IX a.C. As escavações estrangeiras foram suspensas no Iraque por volta de 1990, mas estão agora a ser retomadas e poderão levar a descobertas ainda mais emocionantes.

Sobre o autor: Eric H. Cline is professor of classics and anthropology and director of the Capitol Archaeological Institute at George Washington University, Washington, D. C. An active archaeologist, he has excavated and surveyed in Greece, Crete, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and the United States.

Fonte: CLINE, E. H. Archaeology: An Introduction to the World’s Greatest Sites. Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses, 2016. Capítulo 4: Early Archaeology in Mesopotamia.

Early Archaeology in Mesopotamia

The site of ancient Ur is situated on the Euphrates River in modern Iraq, north of where the river empties into the Persian Gulf. This is the region known as ancient Mesopotamia, a name that means “between the rivers”—that is, the Tigris and Euphrates. Ur was a site famous in antiquity, with all the typical features of a Bronze Age Mesopotamian city, including religious structures known as ziggurats. Beginning in 1922, the site was excavated by Sir Leonard Woolley and his right-hand man, Max Mallowan. But it wasn’t until the fifth field season, in 1926–1927, that they began digging the cemetery at the site—the famous Death Pits of Ur that had captured the attention of Europe.

Royal Burials at Ur

:. Between 1927 and 1929, Sir Leonard Woolley and Max Mallowan uncovered 16 royal burials at Ur. The royal burials date to about 2500 B.C. and were quite impressive compared to the many other burials found in the cemetery at Ur. Each tomb usually had a stone chamber, either vaulted or domed, into which the royal body was placed. The chamber was at the bottom of a deep pit, with access possible only via a steep ramp from the surface. Precious grave goods were mostly found in the burial chamber with the body, while wheeled vehicles, oxen, and attendants were found in both the chamber and in the pit outside.

:. Between 1927 and 1929, Sir Leonard Woolley and Max Mallowan uncovered 16 royal burials at Ur. The royal burials date to about 2500 B.C. and were quite impressive compared to the many other burials found in the cemetery at Ur. Each tomb usually had a stone chamber, either vaulted or domed, into which the royal body was placed. The chamber was at the bottom of a deep pit, with access possible only via a steep ramp from the surface. Precious grave goods were mostly found in the burial chamber with the body, while wheeled vehicles, oxen, and attendants were found in both the chamber and in the pit outside.

:. Numerous attendants were found in the Death Pits: One tomb had more than 70 bodies that went with their master or mistress into the afterlife. Most of these were women, but men were present, as well. Woolley assumed that they had drunk poison after climbing down the ramp into the pit, but CT scans of some of the skulls done in 2009 indicate that at least some of these people had been killed by having a sharp instrument driven into their heads just below and behind the ear while they were still alive. Death would have been instantaneous.

:. The grave goods that Woolley and Mallowan found with the royal bodies were amazing, despite the fact that many of the graves had been looted in antiquity. Among the finds were gold tiaras, gold and lapis jewelry, gold and electrum daggers, and a gold helmet. There were also delicate sculptures, the remains of a wooden harp with ivory and lapis inlays, and a wooden box with inlays that Woolley dubbed the Standard of Ur.

Henry Rawlinson and Paul-Émile Botta

:. Among the first modern scholars and archaeologists who worked in Mesopotamia was Sir Henry Rawlinson, who helped to decipher and translate cuneiform script in the 1830s. Cuneiform is a wedge-shaped writing system that was used to write Akkadian, Babylonian, Hittite, Old Persian, and other languages in the ancient Near East.

1830s. Cuneiform is a wedge-shaped writing system that was used to write Akkadian, Babylonian, Hittite, Old Persian, and other languages in the ancient Near East.

. Rawlinson, who was a British army officer posted to what is now Iran, cracked the secret of cuneiform by translating a trilingual inscription that was written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. Darius the Great of Persia had carved the inscription 400 feet above the desert floor into a cliff face at the site of Behistun in about 519 B.C.

. By 1837, about 10 years before the copying of the entire inscription was completed, Rawlinson had figured out how to read the first two paragraphs of the part that was written in Old Persian. It reportedly took him another 20 years to decipher the Babylonian and Elamite parts of the inscription and successfully read the whole thing.

. Along the way, however, Rawlinson was able to use his knowledge of cuneiform to begin translating some of the inscriptions that British archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard was finding at his excavations in what is now Iraq. In fact, Rawlinson was able to confirm that Layard had found two ancient sites that, up until that point, had been known only from the Bible.

:. Paul-Émile Botta was an Italian-born archaeologist who worked for the French. In December 1842, he began the first archaeological excavations ever conducted in what is now Iraq. Botta’s first efforts were concentrated on the mounds known as Kuyunjik, which are across the river from the city of Mosul. However, he didn’t find much there and quickly abandoned his efforts.

. From one of his workmen, Botta learned that some sculptures had been found at a site called Khorsabad, which was located about 14 miles to the north. In March 1843, he began excavating there and, within a week, began to unearth a great Assyrian palace.

. From one of his workmen, Botta learned that some sculptures had been found at a site called Khorsabad, which was located about 14 miles to the north. In March 1843, he began excavating there and, within a week, began to unearth a great Assyrian palace.

. At first, Botta thought that he had found the remains of ancient Nineveh, but now we know that Khorsabad is the ancient site of Dur Sharrukin, the capital city of the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II (r. 721–705 B.C.).

Austen Henry Layard

:. Beginning in 1845, Sir Austen Henry Layard undertook his initial archaeological efforts at Nimrud, which he first thought was ancient Nineveh. Amazingly, on the first day of digging, his team of six local men found not one but two Assyrian palaces! Today, they are usually called the Northwest and Southwest Palaces.

. From the inscriptions Layard found, it eventually became clear that the Northwest Palace was built by Assurnasirpal II (r. 884–859 B.C.), and the Southwest Palace was built by Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 B.C.). Later, a Central Palace was discovered at the

Layard found, it eventually became clear that the Northwest Palace was built by Assurnasirpal II (r. 884–859 B.C.), and the Southwest Palace was built by Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 B.C.). Later, a Central Palace was discovered at the

site, built by Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 B.C.). Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 B.C.) also had buildings and monuments constructed at the site.

. Layard published a book about his amazing discoveries at Nimrud. The book was called Nineveh and Its Remains, but when the inscriptions from the site were finally deciphered, they confirmed that it was actually ancient Kalhu (biblical Calah), rather than Nineveh.

. As it turns out, Kalhu was the second capital city established by the Assyrians, the first being Assur itself. It served as their capital for almost 175 years, from 879 to 706 B.C. After that, Sargon II moved the capital to Dur Sharrukin for a brief period, and then Sennacherib moved it to Nineveh.

:. In 1849, Layard returned to Mosul for another round of excavations, but this time, his primary focus was Kuyunjik, the mound that Botta had abandoned seven years earlier. Layard’s men immediately began unearthing walls with reliefs and images, and translation of the tablets found there confirmed that this was the actual site of ancient Nineveh. By the time Layard and several other excavators were done, a palace of Sennacherib (r. 704–681 B.C.) had been uncovered, as well as a palace of Assurbanipal, Sennacherib’s grandson (r. 668–627 B.C.).

. Sennacherib, who had moved the Assyrian capital from Dur Sharrukin after he came to the throne, built what he called the Palace without Rival at Nineveh. Today, the palace is probably most famous for the Lachish Room. Here, Layard found wall reliefs showing Sennacherib’s capture of the city of Lachish in 701 B.C. At that time, Lachish was the second most powerful city in Judah; Sennacherib attacked it before proceeding on to besiege Jerusalem.

. The capture of Lachish is described in the Hebrew Bible, as is the siege of Jerusalem. Layard’s discovery was one of the first times that an event from the Bible could be confirmed by extrabiblical sources.

. Twentieth-century excavations at the site of Lachish, in what is now Israel, not only confirmed the destruction of the city in about 701 B.C. but also revealed an Assyrian siege ramp, built of tons of earth and rocks and looking similar to ramps depicted in Sennacherib’s reliefs.

siege ramp, built of tons of earth and rocks and looking similar to ramps depicted in Sennacherib’s reliefs.

. The Nineveh reliefs are full of gruesome scenes, including captives having their tongues pulled out and being flayed alive, along with decapitated heads displayed on a pole. It is universally accepted that the Assyrians actually committed such atrocities, but the depiction of them in Sennacherib’s palace is most likely meant as propaganda—a means to deter other kingdoms from rebellion.

:. It’s important to note that Layard was not a trained archaeologist. He frequently left the middle of rooms unexcavated and wasn’t particularly interested in any of the pottery his men uncovered. He was, however, interested in the inscribed slabs that made up the walls of rooms, as well as the colossal statues. Many of these were shipped back to the British Museum, where they can be seen today.

Continuing Excavations

:. In 1853, Hormuzd Rassam, Layard’s protégé and successor at Nineveh, discovered Assurbanipal’s palace, literally under the nose of Botta’s successor, Victor Place, who was digging in the same spot. ○○ Rassam and his men dug secretly for three straight nights in disputed territory on the mound; when their trenches first revealed the walls and sculptures of the palace, Place could do nothing but congratulate them on their finds.

. Within the palace, Rassam found a tremendous library of cuneiform texts, just as Layard had done previously in Sennacherib’s palace. In fact, it is generally considered that the state archives were split between the two palaces, even though they were two generations apart. Apart from state documents, Rassam found religious, scientific, and literary texts, including copies of the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Babylonian flood story.

. Within the palace, Rassam found a tremendous library of cuneiform texts, just as Layard had done previously in Sennacherib’s palace. In fact, it is generally considered that the state archives were split between the two palaces, even though they were two generations apart. Apart from state documents, Rassam found religious, scientific, and literary texts, including copies of the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Babylonian flood story.

:. In 1872, nearly 20 years after Rassam first found the tablets, a man named George Smith was employed at the British Museum, sorting out the tablets that Rassam had sent back from Nineveh.

. At one point, Smith discovered a large fragment that gave an account of a great flood, similar to the deluge account found in the Hebrew Bible. When Smith announced his discovery at a meeting of the Society of Biblical Archaeology in December 1872, all of London was abuzz with excitement.

. The problem, though, was that a large piece was missing from the middle of the tablet. A reward was promised to anyone who would go look for the missing fragment, and Smith himself decided to take on the challenge, even though he had never been to Mesopotamia and had no training as an archaeologist.

. The problem, though, was that a large piece was missing from the middle of the tablet. A reward was promised to anyone who would go look for the missing fragment, and Smith himself decided to take on the challenge, even though he had never been to Mesopotamia and had no training as an archaeologist.

. Amazingly, just five days after he arrived at Nineveh, Smith found the missing piece by searching through the back-dirt pile of previous excavators. He also found about 300 other pieces from clay tablets that the workers had discarded.

:. The 19th-century excavations at Nimrud, Nineveh, Khorsabad, Ur, Babylon, and other sites began an era of excavation in the region that continues to this day. As recently as 1988, spectacular discoveries were made at Nimrud by local Iraqi archaeologists. They uncovered the graves of several Assyrian princesses from the time of Assurnasirpal II in the 9th century B.C. Foreign excavations were suspended in Iraq around 1990 but are now being resumed and may lead to yet more exciting discoveries.