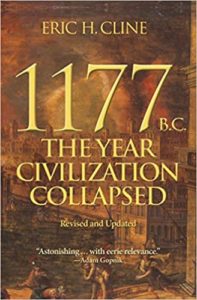

CLINE, E. H. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021 (Revised and Updated Edition) [2014], 304 p. – ISBN 9780691208015.

O livro de Eric H. Cline, da Universidade George Washington, Washington, D.C., é muito interessante. Embora não seja especificamente sobre os filisteus, o livro nos coloca no contexto da chegada dos “povos do mar”, dos quais os filisteus fazem parte, e oferece um panorama dos acontecimentos do Antigo Oriente Médio no final da Idade do Bronze.

O livro de Eric H. Cline, da Universidade George Washington, Washington, D.C., é muito interessante. Embora não seja especificamente sobre os filisteus, o livro nos coloca no contexto da chegada dos “povos do mar”, dos quais os filisteus fazem parte, e oferece um panorama dos acontecimentos do Antigo Oriente Médio no final da Idade do Bronze.

A primeira edição do livro é de 2014. Esta edição de 2021 foi revista e atualizada, incorporando dados arqueológicos mais recentes.

Diz a editora:

Em 1177 a.C., grupos de saqueadores, que hoje chamamos de “povos do mar”, invadiram o Egito. As forças militares egípcias, sob o comando do faraó Ramsés III, conseguiram derrotá-los, mas a vitória enfraqueceu tanto o Egito que logo o então poderoso reino caiu em declínio, assim como a maioria das civilizações vizinhas. Depois de séculos de existência de brilhantes civilizações, o mundo da Idade do Bronze chegou a um fim abrupto e cataclísmico. Os reinos caíram como dominós ao longo de apenas algumas décadas. Não havia mais minoicos ou micênios. Não havia mais troianos, hititas ou babilônios. A prosperidade econômica e cultural do final do segundo milênio a.C., que se estendia da Grécia ao Egito e à Mesopotâmia, deixou repentinamente de existir, junto com sistemas de escrita, tecnologia e arquitetura monumental. Mas os povos do mar sozinhos não poderiam ter causado um colapso tão generalizado. Como isso aconteceu?

Neste novo e importante relato das causas desta “primeira idade das trevas”, Eric H. Cline conta a emocionante história de como o fim foi causado por múltiplos fatores interligados, desde invasão e revolta até terremotos, seca e bloqueio das rotas do comércio internacional. Trazendo à vida o vibrante mundo multicultural dessas grandes civilizações, ele desenha um panorama abrangente dos impérios e povos globalizados da Idade do Bronze Recente e mostra que foi sua própria interdependência que apressou seu colapso dramático e inaugurou uma idade das trevas que durou séculos.

Em uma atraente combinação de narrativa e pesquisa mais recente, 1177 a.C. lança nova luz sobre os processos complexos que deram origem, e finalmente destruíram, as florescentes civilizações do final da Idade do Bronze. E que prepararam o terreno para o surgimento da Grécia clássica.

Há uma versão em português, publicada em Portugal:

CLINE, E. H. 1177 a.C.: o ano em que a civilização colapsou. Odivelas: Alma dos Livros, 2022, 320 p. – ISBN 9789895700363.

Há também uma versão publicada no Brasil:

CLINE, E. H. 1177 a.C.: o ano em que a civilização entrou em colapso. Barueri: Avis Rara, 2023, 224 p. – ISBN 9786559573561.

Veja um vídeo com uma exposição de Eric H. Cline sobre o tema aqui.

In 1177 B.C., marauding groups known only as the “Sea Peoples” invaded Egypt. The pharaoh’s army and navy managed to defeat them, but the victory so weakened Egypt that it soon slid into decline, as did most of the surrounding civilizations. After centuries of brilliance, the civilized world of the Bronze Age came to an abrupt and cataclysmic end. Kingdoms fell like dominoes over the course of just a few decades. No more Minoans or Mycenaeans. No more Trojans, Hittites, or Babylonians. The thriving economy and cultures of the late second millennium B.C., which had stretched from Greece to Egypt and Mesopotamia, suddenly ceased to exist, along with writing systems, technology, and monumental architecture. But the Sea Peoples alone could not have caused such widespread breakdown. How did it happen?

In this major new account of the causes of this “First Dark Ages,” Eric Cline tells the gripping story of how the end was brought about by multiple interconnected failures, ranging from invasion and revolt to earthquakes, drought, and the cutting of international trade routes. Bringing to life the vibrant multicultural world of these great civilizations, he draws a sweeping panorama of the empires and globalized peoples of the Late Bronze Age and shows that it was their very interdependence that hastened their dramatic collapse and ushered in a dark age that lasted centuries.

A compelling combination of narrative and the latest scholarship, 1177 B.C. sheds new light on the complex ties that gave rise to, and ultimately destroyed, the flourishing civilizations of the Late Bronze Age―and that set the stage for the emergence of classical Greece.

Sobre o autor: Eric H. Cline is professor of classics and anthropology and director of the Capitol Archaeological Institute at George Washington University, Washington, D. C. An active archaeologist, he has excavated and surveyed in Greece, Crete, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and the United States.

Eric H. Cline diz no prólogo de 1177 a.C.: o ano em que a civilização entrou em colapso, nas páginas 1-6:

Os guerreiros entraram no cenário mundial e se moveram rapidamente, deixando a morte e a destruição por onde passaram. Os estudiosos modernos referem-se a eles coletivamente como “povos do mar”, mas os egípcios que registraram seu ataque ao país nunca usaram esse termo, identificando-os como grupos independentes em empreitada comum: os Peleset, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Shardana, Danuna e Weshesh – nomes estranhos de pessoas com aparência estrangeira para os egípcios [nota: o nome “povos do mar” foi cunhado por Emmanuel de Rougé em 1867].

Nós sabemos pouco sobre eles, além do que os registros egípcios nos dizem. Não sabemos ao certo de onde veem os povos do mar: talvez da Sicília, Sardenha e Itália, de acordo com um cenário; talvez do Egeu ou da Anatólia ocidental, ou possivelmente até de Chipre ou do Mediterrâneo Oriental. Nenhuma localidade antiga foi identificada como sua origem ou ponto de partida. Pensamos neles como se movendo implacavelmente de um lugar para outro, vencendo países e reinos à medida que avançavam. De acordo com os textos egípcios, eles montaram acampamento na Síria antes de seguirem pela costa de Canaã (que inclui partes da moderna Síria, Líbano e Israel) e para o delta do Nilo, no Egito.

O ano era 1177 a.C. Era o oitavo ano do reinado do faraó Ramsés III. De acordo com os antigos egípcios, e segundo evidências arqueológicas mais recentes, alguns dos povos do mar vieram por terra, outros por mar. Não há vestígios de uniformes ou ferramentas. Imagens antigas retratam um grupo com elmos emplumados, enquanto outro grupo usava turbantes; outros ainda tinham capacetes com chifres ou tinham a cabeça descoberta. Alguns tinham barbas curtas e pontiagudas e estavam vestidos com saiotes curtos, com torso nu ou com túnica; outros não tinham barba e usavam saias mais compridas. Essas observações sugerem que os povos do mar compreendiam grupos diversos de diferentes geografias e culturas. Armados com afiadas espadas de bronze, lanças de madeira com pontas reluzentes de metal, e arcos e flechas, eles vieram em barcos, carroças, carros de boi e carruagens. Embora eu tenha tomado 1177 a.C. como uma data crucial, sabemos que os invasores vieram em ondas sucessivas durante um considerável espaço de tempo. Às vezes os guerreiros vinham sozinhos e às vezes as famílias os acompanhavam.

De acordo com as inscrições de Ramsés III, nenhum país foi capaz de se opor a essa massa de homens. A resistência foi inútil. As grandes potências da época – os  hititas, os micênios, os cananeus, os cipriotas e outros – caíram uma a uma. Alguns dos sobreviventes fugiram da carnificina; outros se amontoavam nas ruínas de suas outrora orgulhosas cidades; outros ainda se uniram aos invasores, aumentando suas fileiras e a complexidade da horda de migrantes. Cada grupo dos povos do mar estava em movimento, cada um aparentemente motivado por razões individuais. Talvez tenha sido o desejo de despojos ou escravos que estimulou alguns; outros podem ter sido compelidos pelas pressões populacionais a migrar para o leste de suas próprias terras no Ocidente.

hititas, os micênios, os cananeus, os cipriotas e outros – caíram uma a uma. Alguns dos sobreviventes fugiram da carnificina; outros se amontoavam nas ruínas de suas outrora orgulhosas cidades; outros ainda se uniram aos invasores, aumentando suas fileiras e a complexidade da horda de migrantes. Cada grupo dos povos do mar estava em movimento, cada um aparentemente motivado por razões individuais. Talvez tenha sido o desejo de despojos ou escravos que estimulou alguns; outros podem ter sido compelidos pelas pressões populacionais a migrar para o leste de suas próprias terras no Ocidente.

Nas paredes do seu templo mortuário em Medinet Habu, perto do Vale dos Reis, disse Ramsés III de maneira concisa:

“Os países estrangeiros fizeram uma conspiração em suas ilhas. De uma só vez as terras foram eliminadas e as pessoas dispersas no conflito. Nenhum país foi capaz de resistir às suas armas, de Hatti, Qode, Karkemish, Arzawa e Alashiya eles foram [eliminados] imediatamente. Um acampamento foi montado em uma localidade de Amurru. Humilharam seu povo, e sua terra nunca tinha enfrentado uma situação como essa. Eles se moveram em direção ao Egito e uma barreira de fogo foi colocada diante deles. Sua confederação era formada pelos Peleset, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Danuna e Weshesh, terras que se uniram. Eles puseram suas mãos sobre estas terras, com corações confiantes e esperançosos”.

Conhecemos as terras conquistadas pelos povos do mar, até porque algumas delas eram famosas naquela época, mas a identidade étnica dos 6 grupos que fizeram isso é bem mais problemática. Por exemplo: Danuna devem ser os Danaos de Homero, os Shekelesh podem ter vindo da Sicília e os Shardana [citados em outro documento] da Sardenha. Mas não há acordo sobre isso entre os estudiosos. E, então, diz Eric H. Cline:

De todos os grupos estrangeiros ativos em cena, apenas um foi identificado com certeza. O Peleset dos povos do mar quase certamente coincide com os filisteus, que, segundo a Bíblia, vieram de Creta.

(…)

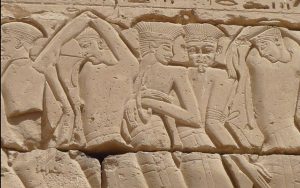

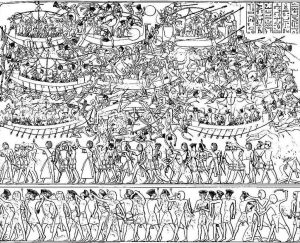

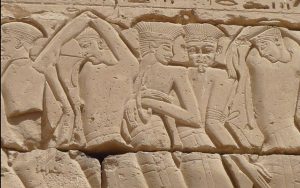

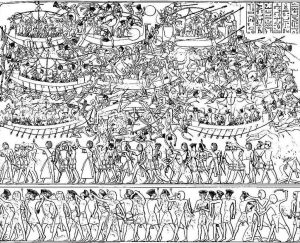

Embora não saibamos com precisão as origens ou a motivação dos invasores, sabemos como eles se parecem – podemos ver seus nomes e rostos gravados nas paredes do templo mortuário de Ramsés III em Medinet Habu. Este sítio antigo é rico tanto em imagens quanto em textos gravados em hieróglifos. As armaduras, armas, roupas, barcos e carros de bois dos invasores carregados de pertences são claramente visíveis nas representações, tão detalhadas que os estudiosos publicaram análises das pessoas individuais e até mesmo dos diferentes barcos mostrados nas cenas.

(…)

Embora o debate acadêmico continue, a maioria dos especialistas concorda que as batalhas terrestres e marítimas descritas nas paredes de Medinet Habu foram provavelmente travadas quase simultaneamente no delta egípcio ou nas proximidades. É possível que elas representem uma única grande batalha, tanto no mar quanto em terra. Alguns estudiosos sugeriram que os exércitos dos povos do mar foram emboscados, sendo pegos de surpresa pelos egípcios. Em qualquer caso, o resultado final não está em questão. Em Medinet Habu, o faraó egípcio diz claramente:

“Eles alcançaram talvez a fronteira de minhas terras, mas não sua semente, e seus corações e almas terminaram para sempre e definitivamente. Aqueles que se reuniram do outro lado do mar tinham uma chama brilhante diante deles na foz do rio, e toda uma barreira de lanças os cercava na praia. Eles foram arrastados para a praia, cercados e vencidos, mortos e despedaçados da cabeça aos pés. Os navios afundaram e as mercadorias caíram na água. Eu me certifiquei de que essas terras evitassem (até mesmo) mencionar o Egito: porque quando pronunciam meu nome em suas terras, então eles são imediatamente queimados”.

Ramsés continua, em um famoso documento conhecido como Papiro Harris, novamente nomeando seus inimigos derrotados:

“Eu derrotei aqueles que os invadiram de suas terras. Eu matei os Danuna [que estão] em suas ilhas, os Tjekker e os Peleset foram incinerados. O Shardana e a Weshesh do mar, eles foram feitos como aqueles que não existem, todos aprisionados, trazidos como cativos para o Egito, como a areia da praia. Eu os estabeleci em fortalezas sujeitas a meu nome. Numerosos eles eram, como se fossem centenas de milhares. Eu taxava todos eles, em tecidos e grãos dos armazéns e celeiros, todos os anos”.

The warriors entered the world scene and moved rapidly, leaving death and destruction in their wake. Modern scholars refer to them collectively as the “Sea Peoples,” but the Egyptians who recorded their attack on Egypt never used that term, instead identifying them as separate groups working together: the Peleset, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Shardana, Danuna, and Weshesh—foreign-sounding names for foreign-looking people.

We know little about them, beyond what the Egyptian records tell us. We are not certain where the Sea Peoples originated: perhaps in Sicily, Sardinia, and Italy, according to one scenario, perhaps in the Aegean or western Anatolia, or possibly even Cyprus or the Eastern Mediterranean. No ancient site has ever been identified as their origin or departure point. We think of them as moving relentlessly from site to site, overrunning countries and kingdoms as they went. According to the Egyptian texts, they set up camp in Syria before proceeding down the coast of Canaan (including parts of modern Syria, Lebanon, and Israel) and into the Nile delta of Egypt.

The year was 1177 BC. It was the eighth year of Pharaoh Ramses III’s reign. According to the ancient Egyptians, and to more recent archaeological evidence, some of the Sea Peoples came by land, others by sea. There were no uniforms, no polished outfits. Ancient images portray one group with feathered headdresses, while another faction sported skullcaps; still others had horned helmets or went bareheaded. Some had short pointed beards and dressed in short kilts, either barehested or with a tunic; others had no facial hair and wore longer garments, almost like skirts. These observations suggest that the Sea Peoples comprised verse groups from different geographies and different cultures. Armed with sharp bronze swords, wooden spears with gleaming metal tips, and bows and arrows, they came on boats, wagons, oxcarts, and chariots. Although I have taken 1177 BC as a pivotal date, we know that the invaders came in waves over a considerable period of time. Sometimes the warriors came alone, and sometimes their families accompanied them.

According to Ramses’s inscriptions, no country was able to oppose this invading mass of humanity. Resistance was futile. The great powers of the day—the Hittites, the Mycenaeans, the Canaanites, the Cypriots, and others—fell one by one. Some of the survivors fled the carnage; others huddled in the ruins of their once-proud cities; still others joined the invaders, swelling their ranks and adding to the apparent complexities of the mob of invaders. Each group of the Sea Peoples was on the move, each apparently motivated by individual reasons. Perhaps it was the desire for spoils or slaves that spurred some; others may have been compelled by population pressures to migrate eastward from their own lands in the West.

On the walls of his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu, near the Valley of the Kings, Ramses said concisely:

The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Khatte, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya on, being cut off at [one time]. A camp [was set up] in one place in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Danuna, and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the lands as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting.

(…)

Of all the foreign groups active in this arena at this time, only one has been firmly identified. The Peleset of the Sea Peoples are generally accepted as none other than the Philistines, who are identified in the Bible as coming from Crete.

(…)

While we do not know with any precision either the origins or the motivation of the invaders, we do know what they look like—we can view their names and faces carved on the walls of Ramses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu. This ancient site is rich in both pictures and stately rows of hieroglyphic text. The invaders’ armor, weapons, clothing, boats, and ox-carts loaded with possessions are all clearly visible in the representations, so detailed that scholars have published analyses of the individual people and even the different boats shown in the scenes.

(…)

Although scholarly debate continues, most experts agree that the land and sea battles depicted on the walls at Medinet Habu were probably fought nearly simultaneously in the Egyptian delta or nearby. It is possible that they represent a single extended battle that occurred both on land and at sea, and some scholars have suggested that both represent ambushes of the Sea Peoples’ forces, in which the Egyptians caught them by surprise. In any event, the end result is not in question, for at Medinet Habu the Egyptian pharaoh quite clearly states:

Those who reached my frontier, their seed is not, their heart and soul are finished forever and ever. Those who came forward together on the sea, the full flame was in  front of them at the river-mouths, while a stockade of lances surrounded them on the shore. They were dragged in, enclosed, and prostrated on the beach, killed, and made into heaps from tail to head. Their ships and their goods were as if fallen into the water. I have made the lands turn back from (even) mentioning Egypt: for when they pronounce my name in their land, then they are burned up.

front of them at the river-mouths, while a stockade of lances surrounded them on the shore. They were dragged in, enclosed, and prostrated on the beach, killed, and made into heaps from tail to head. Their ships and their goods were as if fallen into the water. I have made the lands turn back from (even) mentioning Egypt: for when they pronounce my name in their land, then they are burned up.

Ramses then continues, in a famous document known as the Papyrus Harris, again naming his defeated enemies:

I overthrew those who invaded them from their lands. I slew the Danuna [who are] in their isles, the Tjekker and the Peleset were made ashes. The Shardana and the Weshesh of the sea, they were made as those that exist not, taken captive at one time, brought as captives to Egypt, like the sand of the shore. I settled them in strongholds bound in my name. Numerous were their classes like hundred-thousands. I taxed them all, in clothing and grain from the store-houses and granaries each year.

Mais para o final do livro, no final do capítulo 5, em um item chamado A Review of Possibilities and Complexity Theory, Eric H. Cline resume da seguinte forma o que foi discutido ao longo do livro:

Não existe consenso sobre quem ou o que provocou o colapso de inteiras civilizações no final da Idade do Bronze. Pois certo é que havia importantes civilizações como os minoicos, micênios, hititas, egípcios, babilônios, assírios, cananeus e cipriotas, independentes uma das outras, mas interligadas por rotas de comércio. Certo é também que muitas cidades foram destruídas e as civilizações que floresceram do século XV ao século XIII chegaram ao fim em 1177 a.C. ou pouco depois.

Até hoje não existe uma prova definitiva do que provocou este colapso. Há muitas possibilidades, mas nenhuma parece ter sido capaz de provocar tal catástrofe sozinha. Talvez tenha ocorrido uma “tempestade perfeita” de calamidades? Terremotos? Fome? Seca? Mudanças climáticas? Rebeliões internas? Invasões?

Enfim, ele vai sugerir um conjunto de fatores para explicar o colapso.

There is still no general consensus as to who, or what, caused the destruction or abandonment of each of the major sites within the civilizations that came to an end in the twilight of the Bronze Age. The problem can be concisely summarized as follows:

Major Observations

1. We have a number of separate civilizations that were flourishing during the fifteenth to thirteenth centuries BC in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean, from the Mycenaeans and the Minoans to the Hittites, Egyptians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Canaanites, and Cypriots. These were independent but consistently interacted with each other, especially through international trade routes.

2. It is clear that many cities were destroyed and that the Late Bronze Age civilizations and life as the inhabitants knew it in the Aegean, Eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, and the Near East came to an end ca. 1177 BC or soon thereafter.

3. No unequivocal proof has been offered as to who or what caused this disaster, which resulted in the collapse of these civilizations and the end of the Late Bronze Age.

Discussion of Possibilities

There are a number of possible causes that may have led, or contributed, to the collapse at the end of the Late Bronze Age, but none seems capable of having caused the calamity on its own.A “Perfect Storm” of Calamities?

A. Clearly there were earthquakes during this period, but usually societies can recover from these.

B. There is textual evidence for famine, and now scientific evidence for droughts and climate change, in both the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean, but again societies have recovered from these time and time again.

C. There may be circumstantial evidence for internal rebellions in Greece and elsewhere, including the Levant, although this is not certain. Again, societies frequently survive such revolts. Moreover, it would be unusual (notwithstanding recent experience in the Middle East to the contrary) for rebellions to occur over such a wide area and for such a prolonged period of time.

D. There is archaeological evidence for invaders, or at least newcomers probably from the Aegean region, western Anatolia, Cyprus, or all of the above, found in the Levant from Ugarit in the north to Lachish in the south. Some of the cities were destroyed and then abandoned; others were reoccupied; and still others were unaffected.

E. It is clear that the international trade routes were affected, if not completely cut, for a period of time, but the extent to which this would have impacted the various individual civilizations is not altogether clear—even if some were overly dependent upon foreign goods for their survival, as has been suggested in the case of the Mycenaeans.

(…)

However, despite my comments above, systems collapse might be just too simplistic an explanation to accept as the entire reason for the ending of the Late Bronze Age in the Aegean, Eastern Mediterranean, and Near East. It is possible that we need to turn to what is called complexity science, or, perhaps more accurately, complexity theory, in order to get a grasp of what may have led to the collapse of these civilizations.

Pode ser útil ler uma entrevista com Eric H. Cline, publicada, em espanhol, em 28 de março de 2015, em Mediterráneo Antiguo. Autor: Mario Agudo Villanueva.

Entrevista con Eric H. Cline: “estamos afrontando una situación muy parecida a la que tuvieron que hacer frente en 1177 a.C.”

El final de la Edad del Bronce en el Mediterráneo es uno de los acontecimientos más enigmáticos de nuestra historia. La irrupción de los Pueblos del Mar, sumada a otra serie de acontecimientos, provocó el colapso de los que hasta entonces eran los centros de poder más importantes de la civilización. Hemos querido conocer con más profundidad el problema de la mano de Eric H. Cline, profesor de Historia Antigua y Arqueología de la Universidad George Washington, autor de 1177 a.C. El año que la civilización se derrumbó, editado en castellano por Crítica.

Pregunta – Tras siglos de esplendor, el mundo civilizado se sumergió en una profunda crisis que afectó a todos los ámbitos de la vida cotidiana. Parece improbable que fuera desencadenada únicamente por los Pueblos del Mar. ¿Cuántas causas concurrieron en este cataclismo?

Respuesta – Hay al menos cinco, o quizás seis, que yo ordenaría siguiendo este orden de importancia: cambio climático, sequía, hambruna, terremotos, invasores y rebeliones internas. Uno podría optar por combinar el cambio climático con la sequía, en este caso serían cinco.

Pregunta – ¿Por qué sitúa este momento en el año 1177 a.C.? ¿No deberíamos hablar de un proceso largo y complejo que condujo al final de esta época?

Respuesta – Efectivamente, el proceso de colapso se tomó un siglo, desde alrededor del 1225 al 1125 a.C. , pero 1177 a.C. es un buen punto de referencia, porque es en este año cuando se produjo la segunda invasión de los Pueblos del Mar y también es cuando muchas de las ciudades iniciaron su declive, si no estaban ya destruidas. Entonces, he usado esa fecha como clave del colapso total, así como usamos el 476 como clave de la caída del Imperio Romano, incluso aunque sabemos que no cayó exactamente ese año.

Pregunta – ¿Cuál era el origen de los Pueblos del Mar?

Respuesta – Esta es una excelente pregunta, pero no sabemos la respuesta con certeza. Pienso que el origen de algunos de ellos fue la region de Sicilia, Sardinia, y el sur de Italia (algunos de estos grupos llamados los Shekelesh y los Shardana suenan similares), pero es más que probable se unieran al camino iniciado por otros, pues sabemos que se movieron desde el oeste al este a lo largo del Mediterráneo. Entonces, entre los Pueblos del Mar pueden haber también gentes procedentes de las actuales Grecia y Turquía. Pero no hemos identificado de forma definitiva una tierra de procedencia para ellos.

Pregunta – ¿Cuál fue el legado de los Pueblos del Mar?

Respuesta – Su principal legado ha sido los filisteos y su cultura. El grupo entre los Pueblos del Mar que los egipcios llamaron Peleset es probablemente el grupo que nosotros conocemos como los filisteos de la Biblia. Parece que se asentaron en la region de Canaán y quizás se asimilaron con los locales, antes del auge de Israel.

Pregunta – ¿Podría encontrar paralelismos entre el final de la Edad del Bronce y nuestra crisis actual?

Respuesta – En efecto, actualmente estamos afrontando una situación muy parecida a la que tuvieron que hacer frente en 1177 a.C. – cambio climático, hambruna, sequía, rebeliones y terremotos. Lo único que no tenemos en el escenario actual son los Pueblos del Mar – los misteriosos invasores del otro lado del mar – aunque uno puede sugerir que ISIS o ISIL es nuestra versión de los Pueblos del Mar. Deberíamos agradecer, sin embargo, que estamos lo suficientemente desarrollados como para entender qué está pasando y dar pasos para solucionar las cosas, en vez de aceptar simple y pasivamente que tienen que ocurrir.