Circula na web, entre egiptólogos e curiosos, uma persistente discussão sobre “novas teorias” acerca da construção das pirâmides egípcias, mais especificamente, sobre como teria sido construída a Grande Pirâmide de Quéops.

Segundo alguns especialistas, estas teorias não são assim tão novas, mas esta pode ser uma boa oportunidade para se ler um pouco sobre o assunto.

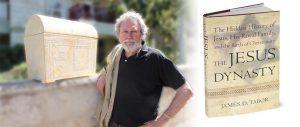

No blog Egyptology News, Andie recomenda, no post Bob Brier on pyramid construction, o artigo do egiptólogo Bob Brier, How to Build a Pyramid, no site da revista Archaeology, publicação de respeito da AIA.

Segundo Andie esta é a melhor síntese que ela conhece sobre novas e velhas teorias acerca das possibilidades de construção de pirâmides.

Quem não acompanhou a discussão, leia primeiro, por favor, a notícia abaixo, da BBC.

Francês diz que desvendou mistério de pirâmide egípcia

O arquiteto francês Jean-Pierre Houdin afirmou ter encontrado a chave para desvendar os mistérios da construção da pirâmide de Quéops, a maior das pirâmides do Egito.

Houdin diz que a construção de 4,5 mil anos, nos arredores do Cairo, foi executada com o auxílio de uma rampa interna para elevar os enormes blocos de pedra até os seus lugares.

As outras teorias afirmam que os 3 milhões de pedras – cada uma com 2,5 toneladas – foram empurradas até os locais em que se encontram por cima de rampas externas.

Houdin passou oito anos estudando o assunto e construiu um modelo computadorizado para ilustrar a sua teoria sobre a construção da pirâmide.

“Esta é melhor que as outras teorias, porque é a única que realmente funciona”, disse o arquiteto ao divulgar a sua tese com o auxílio de uma simulação em três dimensões.

Rampa externa

Ele acredita que uma rampa externa foi usada apenas para construir os primeiros 43 metros e que, então, foi construída a rampa interna para transportar os blocos até o cume da construção, de 137 metros de altura.

A pirâmide foi construída para servir de tumba ao faraó Khufu, também conhecido como Quéops.

A grande galeria no interior da pirâmide, outra fonte de mistério para egiptólogos, teria sido usada para abrigar um enorme contrapeso que teria suspendido as 60 lajes de granito que ficam acima da Câmara Real.

“Essa teoria vai contra as duas principais teses aceitas até hoje”, disse o egiptólogo Bob Brier à agência de notícias Reuters.

‘Erradas’

“Faz 20 anos que as ensino, mas no fundo, sei que elas estão erradas”, admitiu o especialista.

De acordo com Houdin, uma rampa externa até o alto da pirâmide teria tapado a vista e deixado pouco espaço para trabalhar, enquanto uma longa rampa frontal necessitaria de pedras demais.

Além disso, há muito poucos indícios de que jamais tenham sido montadas rampas externas no entorno da pirâmide.

Houdin disse ainda que, usando a técnica postulada por ele, a pirâmide pode ter sido construída por apenas 4 mil pessoas, em vez das 100 mil calculadas por outras teorias.

O arquiteto espera reunir um grupo de especialistas para comprovar a teoria com o auxílio de radares e outros métodos não invasivos.

Fonte: BBC Brasil – 31 de março, 2007

How to Build a Pyramid

by Bob Brier

Hidden ramps may solve the mystery of the Great Pyramid’s construction.

Of the seven wonders of the ancient world, only the Great Pyramid of Giza remains. An estimated 2 million stone blocks weighing an average of 2.5 tons went into its construction. When completed, the 481-foot-tall pyramid was the world’s tallest structure, a record it held for more than 3,800 years, when England’s Lincoln Cathedral surpassed it by a mere 44 feet.

We know who built the Great Pyramid: the pharaoh Khufu, who ruled Egypt about 2547-2524 B.C. And we know who supervised its construction: Khufu’s brother, Hemienu. The pharaoh’s right-hand man, Hemienu was “overseer of all construction projects of the king” and his tomb is one of the largest in a cemetery adjacent to the pyramid.

What we don’t know is exactly how it was built, a question that has been debated for millennia. The earliest recorded theory was put forward by the Greek historian Herodotus, who visited Egypt around 450 B.C., when the pyramid was already 2,000 years old. He mentions “machines” used to raise the blocks and this is usually taken to mean cranes. Three hundred years later, Diodorus of Sicily wrote, “The construction was effected by mounds” (ramps). Today we have the “space alien” theory–those primitive Egyptians never could have built such a fabulous structure by themselves; extraterrestrials must have helped them.

Modern scholars have favored these two original theories, but deep in their hearts, they know that neither one is correct. A radical new one, however, may provide the solution. If correct, it would demonstrate a level of planning by Egyptian architects and engineers far greater than anything ever imagined before.

According to the new theory, an external ramp was used to build the lower third of the pyramid and was then cannibalized, its blocks taken through an internal ramp for the higher levels of the structure. (Dassault Systemes) [LARGER IMAGE]

The External Ramp and Crane Theories

The first theory is that a ramp was built on one side of the pyramid and as the pyramid grew, the ramp was raised so that throughout the construction, blocks could be moved right up to the top. If the ramp were too steep, the men hauling the blocks would not be able to drag them up. An 8-percent slope is about the maximum possible, and this is the problem with the single ramp theory. With such a gentle incline, the ramp would have to be approximately one mile long to reach the top of the pyramid. But there is neither room for such a long ramp on the Giza Plateau, nor evidence of such a massive construction. Also, a mile-long ramp would have had as great a volume as the pyramid itself, virtually doubling the man-hours needed to build the pyramid. Because the straight ramp theory just doesn’t work, several pyramid experts have opted for a modified ramp theory.

This approach suggests that the ramp corkscrewed up the outside of the pyramid, much the way a mountain road spirals upward. The corkscrew ramp does away with the need for a massive mile-long one and explains why no remains of such a ramp have been found, but there is a flaw with this version of the theory. With a ramp corkscrewing up the outside of the pyramid, the corners couldn’t be completed until the final stage of construction. But careful measurements of the angles at the corners would have been needed frequently to assure that the corners would meet to create a point at the top. Dieter Arnold, a renowned pyramid expert at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, comments in his definitive work, Building in Egypt: “During the whole construction period, the pyramid trunk would have been completely buried under the ramps. The surveyors could therefore not have used the four corners, edges, and foot line of the pyramid for their calculations.” Thus the modified ramp theory also has a serious problem.

The second theory centers on Herodotus’s machines. Until recently Egyptian farmers used a wooden, cranelike device called a shadouf to raise water from the Nile for irrigation. This device can be seen in ancient tomb paintings, so we know it was available to the pyramid builders. The idea is that hundreds of these cranes at various levels on the pyramid were used to lift the blocks. One problem with this theory is that it would involve a tremendous amount of timber and Egypt simply didn’t have forests to provide the wood. Importing so much lumber would have been impractical. Large timbers for shipbuilding were imported from Lebanon, but this was a very expensive enterprise.

Perhaps an even more fatal flaw to the crane theory is that there is nowhere to place all these cranes. The pyramid blocks tend to decrease in size higher up the Great Pyramid. I climbed it dozens of times in the 1970s and ’80s, when it was permitted, and toward the top, the blocks sometimes provide only 18 inches of standing room, certainly not enough space for cranes large enough to lift heavy blocks of stone. The crane theory can’t explain how the blocks of the Great Pyramid were raised. So how was it done?

The Internal Ramp Theory

A radical new idea has recently been presented by Jean-Pierre Houdin, a French architect who has devoted the last seven years of his life to making detailed computer models of the Great Pyramid. Using start-of-the-art 3-D software developed by Dassault Systemes, combined with an initial suggestion of Henri Houdin, his engineer father, the architect has concluded that a ramp was indeed used to raise the blocks to the top, and that the ramp still exists–inside the pyramid!

The theory suggests that for the bottom third of the pyramid, the blocks were hauled up a straight, external ramp. This ramp was far shorter than the one needed to reach the top, and was made of limestone blocks, slightly smaller than those used to build the bottom third of the pyramid. As the bottom of the pyramid was being built via the external ramp, a second ramp was being built, inside the pyramid, on which the blocks for the top two-thirds of the pyramid would be hauled. The internal ramp, according to Houdin, begins at the bottom, is about 6 feet wide, and has a grade of approximately 7 percent. This ramp was put into use after the lower third of the pyramid was completed and the external ramp had served its purpose.

The design of the internal ramp was partially determined by the design of the interior of the pyramid. Hemienu knew all about the problems encountered by Pharaoh Sneferu, his and Khufu’s father. Sneferu had considerable difficulty building a suitable pyramid for his burial, and ended up having to construct three at sites south of Giza! The first, at Meidum, may have had structural problems and was never used. His second, at Dashur–known as the Bent Pyramid because the slope of its sides changes midway up–developed cracks in the walls of its burial chamber. Huge cedar logs from Lebanon had to be wedged between the walls to keep the pyramid from collapsing inward, but it too was abandoned. There must have been a mad scramble to complete Sneferu’s third and successful pyramid, the distinctively colored Red Pyramid at Dashur, before the aging ruler died.

From the beginning, Hemienu planned three burial chambers to ensure that whenever Khufu died, a burial place would be ready. One was carved out of the bedrock beneath the pyramid at the beginning of its construction. In case the pharaoh had died early, this would have been his tomb. When, after about five years, Khufu was still alive and well, the unfinished underground burial chamber was abandoned and the second burial chamber, commonly called the Queen’s Chamber, was begun. Some time around the fifteenth year of construction Khufu was still healthy and this chamber was abandoned unfinished and the last burial chamber, the King’s Chamber, was built higher up–in the center of the pyramid. (To this day, Khufu’s sarcophagus remains inside the King’s Chamber, so early explorers of the pyramid incorrectly assumed that the second chamber had been for his queen.)

Huge granite and limestone blocks were needed for the roof beams and rafters of the Queen’s and King’s Chambers. Some of these beams weigh more than 60 tons and are far too large to have been brought up through the internal ramp. Thus the external ramp had to remain in use until the large blocks were hauled up. Once that was done, the external ramp was dismantled and its blocks were led up the pyramid via the internal ramp to build the top two-thirds of the pyramid. Perhaps most blocks in this portion of the pyramid are smaller than those at the bottom third because they had to move up the narrow internal ramp.

There were several considerations that went into designing the internal ramp. First, it had to be fashioned very precisely so that it didn’t hit the chambers or the internal passageways that connect them. Second, men hauling heavy blocks of stones up a narrow ramp can’t easily turn a 90-degree corner; they need a place ahead of the block to stand and pull. The internal ramp had to provide a means of turning its corners so, Houdin suggests, the ramp had openings there where a simple crane could be used to turn the blocks.

There are plenty of theories about how the Great Pyramid could have been built that lack evidence. Is the internal ramp theory any different? Is there any evidence to support it? Yes.

A bit of evidence appears to be one of the ramp’s corner notches used for turning blocks. It is two-thirds of the way up the northeast corner–precisely at a point where Houdin predicted there would be one. Furthermore, in 1986 a member of a French team that was surveying the pyramid reported seeing a desert fox enter it through a hole next to the notch, suggesting that there is an open area close to it, perhaps the ramp. It seems improbable that the fox climbed more than halfway up the pyramid. More likely there is some undetected crevice toward the bottom where the fox entered the ramp and then made its way up the ramp and exited near the notch. It would be interesting to attach a telemetric device to a fox and send him into the hole to monitor his movements! The notch is suggestive, but there is another bit of evidence supplied by the French mentioned earlier that is far more compelling.

When the French team surveyed the Great Pyramid, they used microgravimetry, a technique that enabled them to measure the density of different sections of the pyramid, thus detecting hidden chambers. The French team concluded that there were no large hidden chambers inside it. If there was a ramp inside the pyramid, shouldn’t the French have detected it? In 2000, Henri Houdin was presenting this theory at a scientific conference where one of the members of the 1986 French team was present. He mentioned to Houdin that their computer analysis of the pyramid did yield one curious image, something they couldn’t interpret and therefore ignored. That image showed exactly what Jean-Pierre Houdin’s theory had predicted–a ramp spiraling up through the pyramid.

Far from being just another theory, the internal ramp has considerable evidence behind it. A team headed by Jean-Pierre Houdin and Rainer Stadlemann, former director of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo and one of the greatest authorities on pyramids, has submitted an application to survey the Great Pyramid in a nondestructive way to see if the theory can be confirmed. They are hopeful that the Supreme Council of Antiquities will grant permission for a survey. (Several methods could be used, including powerful microgravimetry, high-resolution infrared photography, or even sonar.) If so, sometime this year we may finally know how Khufu’s monumental tomb was built. One day, if it is indeed there, we might just be able to remove a few blocks from the exterior of the pyramid and walk up the mile-long ramp Hemienu left hidden within the Great Pyramid.

Bob Brier is a senior research fellow at the C. W. Post Campus of Long Island University and a contributing editor to ARCHAEOLOGY.

Fonte: Bob Brier – Archaeology: Volume 60 Number 3, May/June 2007