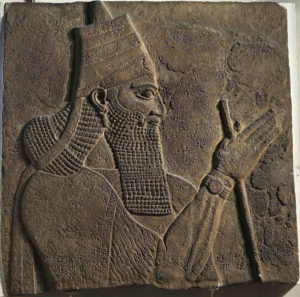

Reli um interessante artigo de Peter Dubovský, professor do Pontifício Instituto Bíblico, sobre as campanhas de Tiglat-Pileser III, rei da Assíria, nos territórios da Síria e da Palestina, nos anos de 734-732 a.C.: “As campanhas militares de Tiglat-Pileser III em 734-732 a.C.: o contexto histórico de Is 7, 2Rs 15-16 e 2Cr 27-28”.

Esta época e este tema muito me interessam, pois trato do assunto, no que diz respeito a Israel, em três disciplinas: Literatura Profética, ao falar dos profetas do século VIII a.C.; Literatura Deuteronomista, ao tratar do contexto da Obra Histórica Deuteronomista; e História de Israel, naturalmente, ao tratar do reino de Israel norte na segunda metade do século VIII a.C.

O que se segue abaixo é um resumo do artigo, bem simplificado, quase como se fossem notas de leitura. O artigo, em inglês, pode ser lido online aqui ou pode-se fazer o download do texto em pdf aqui.

DUBOVSKY, P. Tiglath-pileser III’s Campaigns in 734-732 B.C.: Historical Background of Isa 7; 2 Kgs 15-16 and 2 Chr 27-28. Biblica, Vol. 87, No. 2 (2006), pp. 153-170.

O artigo está dividido em três partes: a primeira reconstrói o percurso das campanhas de Tiglat-Pileser III em 734-732 a.C., a segunda investiga a logística destas campanhas militares e a terceira avalia os resultados destas campanhas.

campanhas militares e a terceira avalia os resultados destas campanhas.

O objetivo do artigo é, a partir das ações de Tiglat-Pileser III, avaliar as consequências políticas e religiosas para os reinos de Israel e Judá na segunda metade do século VIII a.C.

Fontes e contexto histórico

Fontes

Os documentos que temos sobre as campanhas de Tiglat-Pileser III no Levante são de dois tipos: bíblicos e assírios.

Os textos bíblicos avaliam o impacto das campanhas de Tiglat-Pileser III sobre o reino de Israel norte (2Rs 15,29-31) e sobre o reino de Judá (2Rs 15,32-16,20;Is 7,1-25;2Cr 27,1-28,27).

Os textos assírios estão em três Anais de Tiglat-Pileser III (18,23,24), três inscrições sumárias (4,9,13), um Cânon Epônimo (Cb) e várias cartas (2064, 2417, 2430, 2686, 2715, 2716, 2766, 2767).

Além dos textos assírios, há relevos de Nimrud, capital assíria, com cenas destas campanhas. E há dados arqueológicos provenientes de Israel.

Contexto histórico

Parte deste contexto histórico é descrito nos livros de História de Israel como a guerra siro-efraimita, ou seja, uma invasão de Judá por Damasco e Samaria.

É que já em 738 a.C. Israel começara a pagar tributo a Tiglat-Pileser III, quando governava, em Samaria, Menahem. Contudo, grupos antiassírios assassinaram Pecahia, filho e sucessor de Menahem, e Pecah, que subiu ao poder, associou-se a Rasin, rei de Damasco, para enfrentar a interferência assíria na região. Desta campanha deveria participar Acaz, rei de Jerusalém, que ao se recusar, teve seu território e seu governo ameaçado com uma invasão de Judá por Pecah e Rasin. Acreditando não poder se defender sozinho, Acaz chamou em seu socorro o rei assírio Tiglat-Pileser III. Assim relatam as fontes bíblicas.

Muitos autores defendem, entretanto, que a invasão de Judá por Damasco e Samaria teve como motivação primeira a ocupação de territórios judaítas na Transjordânia e não se configurava inicialmente como uma rebelião antiassíria. Do mesmo modo a motivação da Fenícia e dos filisteus seria a expansão comercial na costa mediterrânea através do controle de portos e rotas comerciais.

Porém, qualquer que tenha sido a motivação desta aliança regional, esta articulação por uma independência econômica pode ter sido vista pela Assíria como uma ameaça aos seus interesses na região, pois todos os governantes da Transjordânia ao Mediterrâneo estavam unidos em uma coalizão que controlava os portos e as maiores rotas comerciais da região.

Como dissemos, segundo os textos bíblicos, Judá vê este movimento dos vizinhos como ameaça ao seu território e pede a ajuda de Tiglat-Pileser III. Vale porém observar que tal pedido de ajuda não é mencionado nas fontes assírias.

1. Reconstrução da campanha assíria em três fases

O avanço assírio na região pode ser visto em três fases: costa, Transjordânia, região central.

1. A primeira parte da campanha assíria foi dirigida à região filisteia. Gaza era o centro da resistência. Tiglat-Pileser avançou ao longo da região costeira da Síria e da Fenícia, capturou Tiro e seu rei acabou reconhecendo a soberania assíria. Por outro lado, enquanto o exército assírio avançava em direção a Gaza, o rei da cidade a abandonou, fugindo para o Egito.

2. A segunda fase da campanha assíria levou a um primeiro ataque a Damasco e à conquista da Transjordânia. As fontes indicam que Tiglat-Pileser venceu os arameus em batalha, porém foi incapaz de capturar Damasco. Mas ele atacou e destruiu várias cidades da região de Damasco e ocupou o sul da Síria e norte da Transjordânia. Entre os inimigos vencidos deve ser contabilizada também a rainha árabe Samsi, que participava da coalizão.

3. A terceira fase da campanha levou à conquista da Galileia, de Israel e de Damasco. Esta fase está documentada tanto pelas fontes assírias quanto pelas fontes bíblicas. A população da Galileia foi deportada e um grande saque foi feito na Galileia. Em Samaria, Oseias, governante pró-assírio, substituiu o rei Pecah, que foi assassinado. Por isso, Samaria foi poupada. Finalmente, Tiglat-Pileser III atacou e conquistou Damasco, executando seu rei Rezin. Então, ele estabeleceu seu quartel-general em Damasco, onde recebeu a homenagem de seus vassalos. Inclusive de Acaz, rei de Judá.

2. A logística das campanhas de Tiglat-Pileser III

Tudo indica que o sucesso de Tiglat-Pileser III se deve a um cuidadoso planejamento desta ofensiva.

Tudo indica que o sucesso de Tiglat-Pileser III se deve a um cuidadoso planejamento desta ofensiva.

Em primeiro lugar ele não ataca, de início, os centros de poder na região, Damasco e Samaria, mas toma primeiro a região costeira. Para um exército fortemente baseado na cavalaria e em carros de combate, esta região plana lhe permitiu um rápido avanço das tropas. Em seguida ele enfraquece Damasco, ao destruir as cercanias da capital e as plantações da região, criando, assim, uma situação de escassez de alimentos para os arameus. Nesta mesma ocasião, ele realiza um ataque surpresa contra as forças árabes da Transjordânia, submetendo a região inteira, o que incluiu também Edom, Moab e Amon. Toda esta região começou a pagar tributo para a Assíria.

Deste modo, ele criou um semicírculo formado pelos territórios de seus aliados (Gaza, Judá, Edom, Moab, Amon e Galaad), isolando a coalizão de seu maior suporte, o Egito, que ficou sem nenhuma rota para poder interferir na região. O resultado foi que os maiores centros da região, Damasco e Samaria, ficaram totalmente isolados e a coalizão se desfez.

Esta estratégia não era nova. Já fora usada por Tiglat-Pileser III antes disso em outra região, e será usada novamente por seu filho, e um de seus sucessores, Sargão II.

3. O resultado das campanhas de Tiglat-Pileser III

Por causa da grande instabilidade em que estava o Antigo Oriente Médio nesta época, Tiglat-Pileser III sabia que se deixasse os territórios sem ocupação após a conquista, ele teria perdido os resultados alcançados. Assim, algumas medidas foram tomadas, como:

Deportações: embora a lista detalhada de deportados esteja corrompida nos Anais de Tiglat-Pileser III, muitos pesquisadores consideram razoável o número total de 13.520 pessoas, sendo a maioria destas pessoas provenientes da Síria, de Israel e dos árabes da rainha Samsi. Dezenas de pequenas cidades na Síria e em Israel foram destruídas. Em Israel, por exemplo, a arqueologia documentou a destruição de Hasor, Dan, Tel Kinneret, Betsaida, Bet-shean, Tel Hadar, Meguido, Yoqneam, Aco, Dor e de outras localidades.

Tributos: Tiglat-Pileser III se apossou de 80 talentos de ouro e 2800 talentos de prata [um talento pesava cerca de 34 kg], além das propriedades dos reis Hiram, de Tiro, Hanunu, de Gaza, e da rainha Samsi, dos árabes. E de alguns outros milhares de proprietários das regiões conquistadas.

Reorganização administrativa: Tiglat-Pileser III incorporou à Assíria todos os territórios dos arameus, nomeando um governador assírio para a província de Damasco. Em Israel os assírios se apossaram da maior parte do país, constituindo as províncias de Dor (na costa), Meguido (Galileia) e Galaad (Transjordânia). Samaria e Jerusalém permaneceram com seus reis nativos: Oseias, em Samaria e Acaz, em Jerusalém. Mas agora eram reis vassalos da Assíria que pagavam tributos e se submetiam às ordens de Tiglat-Pileser III.

Conclusão

Assim termina Peter Dubovský seu artigo:

Esta revisão das consequências das campanhas de Tiglat-Pileser III indica que os assírios usaram vários meios para manter o território sob seu controle. A destruição das cidades, pesados tributos e pilhagem de regiões inteiras debilitaram economicamente a região. Embora os números de deportados sejam imprecisos, a deportação em massa dos habitantes locais por Tiglat-Pileser III e sua substituição por exilados de outras partes do Império enfraqueceram a resistência local. Finalmente, a reorganização administrativa fortaleceu o controle assírio e manteve a corte real em Nimrud informada regularmente sobre os desenvolvimentos mais recentes no Levante. Assim, a combinação de logística sofisticada com boa administração era um dos pré-requisitos do controle assírio bem-sucedido do Levante.

Peter Dubovský é professor de exegese do Antigo Testamento no Pontifício Instituto Bíblico, Roma. Foi nomeado Reitor do Bíblico, pelo Papa Francisco, em 11 de setembro de 2023.