Scholars should remind the media that the best constructs of the data are usually the result of a slow, methodical, scholarly process… (Christopher A. Rollston)

Recomendo os textos de Christopher A. Rollston, da Universidade George Washington, Washington, D.C., USA:

:. The Putative Bulla of Isaiah the Prophet: Not so Fast – 22 February 2018

The Old Hebrew bulla excavated by Dr. Eilat Mazar, and published in Biblical Archaeology Review (March-May 2018) in an article entitled _Is this the Prophet Isaiah’s Signature(pages 65-73, notes on page 92) is of much interest.

Numerous stamp seals and bullae have been discovered in the Iron Age Levant. For a synopsis of the use and significance, see the article entitled “Seals and Scarabs” (Volume 5, pages 141-146 in _The New Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible_, Nashville, Abingdon Press, 2009, available via my www.academia.edu page).

This new bulla consists of three registers. Much of the top portion of this bulla is missing (including much of the top register), so the bulla is not fully preserved. The first register has no legible letters (although some iconography is preserved). The second register of the bulla reads “L-yš‘yh[w].” The third register has three preserved letters: “nby.”

Although cautious, it is stated in the press release and in the article itself that this bulla (a lump of clay that has been impressed by a seal) may say “Belonging to Isaiah the Prophet” (note that the lamed [L] at the beginning of the bulla is best translated “belonging to,” and the personal name after this lamed is the personal name “Isaiah” (with the Yahwistic theophoric mostly preserved). The third register, as noted, has the letters nby. Note also that the first the two Hebrew consonants for the word “prophet” are nun and bet, that is, nb).

It would be nice if this bulla did refer to the prophet Isaiah of the Bible, but it would not be wise to assume that this bulla definitely reads that way or that it definitely refers to Isaiah the prophet. In this regard, I very much applaud Dr. Mazar for not assuming that this bulla is definitively that of Isaiah the prophet. That is, the operative word is “may.”

In any case, here are briefly some of the reasons for my methodological caution regarding the assumption that this is a bulla associated with Isaiah the Judean prophet of the eighth century:

:. The Isaiah Bulla from Jerusalem: 2.0 – 23 February 2018

The Old Hebrew bulla excavated by Dr. Eilat Mazar, and published in Biblical Archaeology Review (March-May 2018) in an article entitled _Is this the Prophet Isaiah’s Signature(pages 65-73, notes on page 92) is of much interest, as noted in my previous post on this subject.

Date: this inscription putatively dates to the 8th century or the early 7th century. That is, I would emphasize that the script is the script of the late 8th or early 7th century BCE, and there is no way to be more precise than that. And, of course, the archaeological context is not such that the date can be stated to be only the 8th century. Ultimately, a date in the late 8th century is permissible, but so is a date in the early- to mid- 7th century. We must be candid about that.

In any case, within this post, I wish to emphasize certain things that I mentioned in the previous post and also especially to flesh out some of the possibilities for the second word, that is, word, or word fragment, that is present on the third register: nun, bet, yod. As with my previous post, this will be done in brief. I will publish a full journal article on this bulla at a later date in the near future. In any case, my view is that this second word could be a patronymic (in which case this bulla is certainly not Isaiah the Prophet’s as his father was Amoz), a title, or a gentilic.

:. The ‘Isaiah Bulla’ and the Putative Connection with Biblical Isaiah: 3.0 – 26 February 2018

I here posting some additional details about this bulla, especially regarding the three letters on the third register, heavily incorporating data from my previous two blog posts. Note that this third blog post is the basis for a forthcoming article in a traditional publication venue (i.e., a print publication, rather than just a blog).

(…)

Discussion of Bulla

__

Material: Impressed Clay.

Condition of Bulla: Partially Broken.

Reading of Bulla: First Register: Partially broken, fragmentary iconograhic element; Second Register: L-yš‘yh[w]; Third Register: nby. Note the absence of bn “son of” (but note that this morpheme is sometimes absent from patronymics in the epigraphic record).

Thus, the bulla reads “Yešayahu, nby”

NB: The word that follows the first personal name on a seal (and, thus, a bulla) is normally: a patronymic, a gentilic (descriptor), or a title.

__

Date: this inscription putatively dates to the 8th century or the early 7th century. That is, I would emphasize that the script is the script of the late 8th or early 7th century BCE, and there is no way to be more precise than that. And, of course, the archaeological context is not such that the date can be stated to be only the 8th century. Ultimately, a date in the late 8th century is permissible, but so is a date in the early 7th century.

__

Potential Problems with understanding nby on the third register as prophet, that is, potential problems with assuming that the third register is to be understood as reading: nby[’]:

Leia Mais:

Isaías o profeta? Provavelmente não

Entrevista com Eilat Mazar

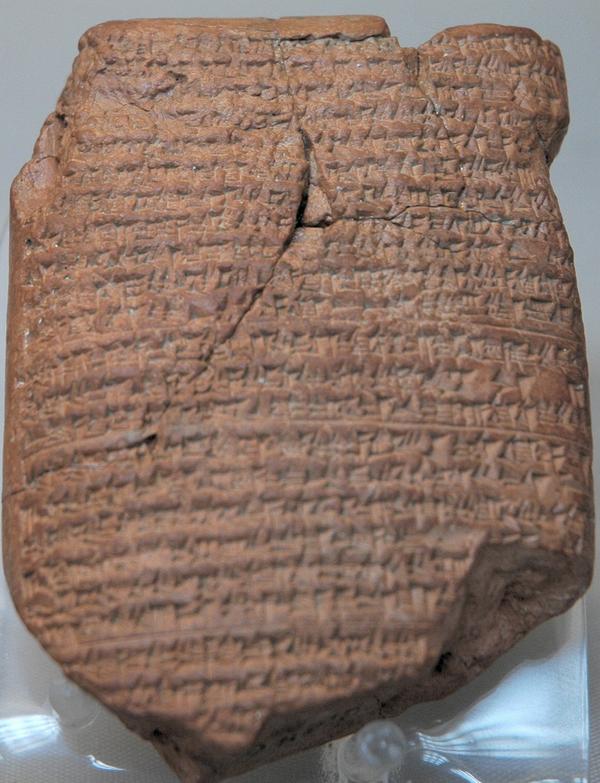

![TIBERIEVM PON]TIVS PILATVS PRAEF]ECTUS IVDA[EA]E - Inscrição de Cesareia - Museu de Israel, Jerusalém TIBERIEVM PON]TIVS PILATVS PRAEF]ECTUS IVDA[EA]E - Inscrição de Cesareia - Museu de Israel, Jerusalém](https://www.airtonjo.com/images/pilatos-1.jpg)