Especialistas avaliam que o P137 foi escrito entre 150 e 250 d.C. O manuscrito mede apenas 4,4 x 4 cm, e contém algumas letras dos versículos 7–9 e 16–18 do capítulo 1 do evangelho de Marcos. Mesmo que não seja tão antigo quanto muitos esperavam – fora divulgado que seria do século I -, o P137 ainda é uma descoberta significativa, pois é provável que este seja o mais antigo fragmento do evangelho de Marcos até agora descoberto.

Para entender o caso, leia dois posts de fevereiro de 2012:

Descoberto fragmento de Marcos do século I?

Esclarecimentos sobre o fragmento de Marcos do século I

Depois, leia*:

Despite Disappointing Some, New Mark Manuscript Is Earliest Yet

By Elijah Hixson – Christianity Today: May 30, 2018

Bible scholars have been waiting for the Gospel fragment’s publication for years.

The Egypt Exploration Society has recently published a Greek papyrus that is likely the earliest fragment of the Gospel of Mark, dating it from between A.D. 150–250. One might expect happiness at such a publication, but this important fragment actually disappointed many observers. The reason stems from the unusual way that this manuscript became famous before it became available.

Second (or Third) Things First

In late 2011, manuscript scholar Scott Carroll—then working for what would become the Museum of the Bible in Washington D.C.—tweeted the tantalizing announcement that the earliest-known manuscript of the New Testament was no longer the second-century John Rylands papyrus (P52). In early 2012, Daniel B. Wallace, senior research professor of New Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary, seemed to confirm Carroll’s statement. In a debate with Bart D. Ehrman, Wallace reported that a fragment of Mark’s gospel, dated to the first century, had been discovered.

As unlikely as a first-century Gospel manuscript is, the fragment was allegedly dated by a world-class specialist. This preeminent authority was not an evangelical Christian, either. He had no apologetic motive for assigning the early date. The manuscript, Wallace claimed, was to be published later that year in a book from Brill, an academic publisher that has since begun publishing items in the Museum of the Bible collection. When pressed for more information, Wallace refrained from saying anything new. He later signed a non-disclosure agreement and was bound to silence until the Mark fragment was published.

As a general rule, earlier manuscripts get us closer to the original text than later manuscripts because there are assumed to be fewer copies between them and the autographs (the original copies of the NT writings, most likely lost to history). Naturally, this news of a first-century copy of Mark generated a great deal of interest.

A first-century fragment of Mark’s gospel would be significant for several reasons. First, the earliest substantial manuscripts of the New Testament come from the third century. Any Christian text written earlier than A.D. 200 is a rare and remarkable find, much less one written before the early 100s. Second, early fragments of Mark’s gospel are scarce. Not all books of the New Testament are equally well-represented in our manuscripts, especially early on. There are several early papyri of Matthew and John, but before this new fragment was published, there was only one existing copy of Mark’s gospel produced before the 300s. Finally, a first-century manuscript of Mark would be the earliest manuscript of the New Testament to survive from antiquity, written within 40 years of when the Holy Spirit inspired the original through the pen of the evangelist himself. Needless to say, a first-century fragment of Mark was a bombshell.

Out of the Garbage Dump

Six years came and went, and there was no “first-century Mark” fragment. But information kept leaking. On stage at a conference in 2015, Scott Carroll told Josh McDowell that the manuscript had been for sale at least twice, after the first attempt was unsuccessful.

It was difficult to know who had even seen the manuscript. Only Carroll would publicly state that he had seen it. Carroll claimed to have seen the fragment in person twice, both times in the possession of Dirk Obbink. Obbink is a renowned papyrologist at the University of Oxford, and he is almost certainly the non-evangelical specialist to whom Wallace attributed the first-century date. New Testament scholars Craig Evans and Gary Habermas were among others who spoke about the fragment, generating even more excitement.

The manuscript has finally been published, but some are disappointed because it is not what they were hoping for: It’s not from the first-century.

The fragment, designated P137, was not published in a Brill volume as Wallace had predicted, nor is it part of the holdings of the Museum of the Bible in Washington D.C. as many had assumed it would be. Instead, it was published in the latest installment of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri series by the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) with the identifier P.Oxy. 83.5345.

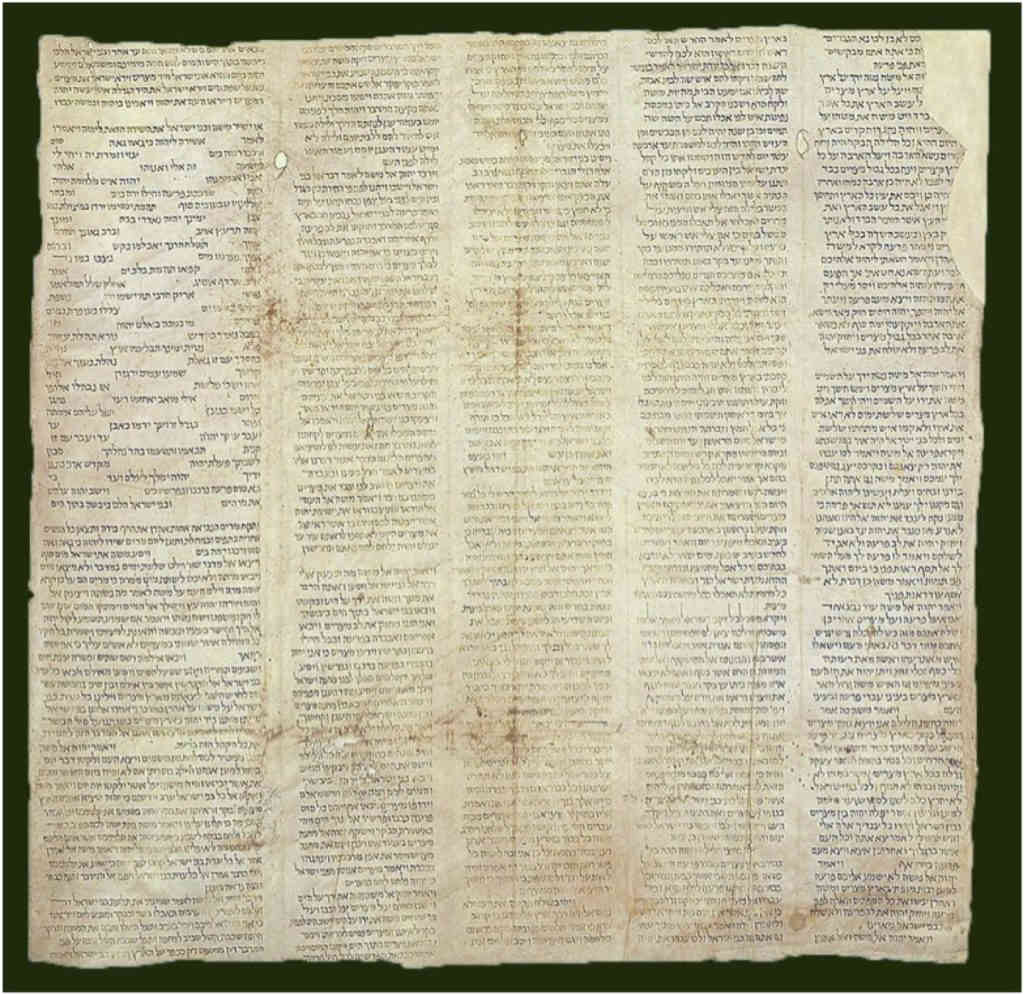

The Oxyrhynchus papyri constitute a collection of hundreds of thousands of manuscript fragments excavated from an ancient Egyptian garbage dump near Oxyrhynchus between 1896 and 1906. Since the first volume was produced in 1898, only about one percent of the collection has been published. Among the papyri are biblical texts, apocryphal texts, classical texts, tax receipts, letters, and even a contract that stipulates the pre-determined outcome of a wrestling match.

The publication of P137 was prepared by Oxford papyrologists Daniela Colomo and Dirk Obbink. Although news releases from the EES about individual papyri are highly unusual, the organization issued a statement last week reporting that P137 was excavated probably in 1903, that Obbink had previously shown the papyrus to visitors to Oxford, and that it had been preliminarily dated to the first century. Obbink and Colomo admit in the edition that the handwriting is difficult to date. Scott Carroll stated that P137 is indeed the manuscript he had spoken about as “first-century Mark,” and Dan Wallace finally broke his six-year silence on the matter.

On the basis of the handwriting, Obbink and Colomo estimate that the manuscript was written in the range of A.D. 150–250. The manuscript itself is tiny, only 4.4 x 4 cm. It contains a few letters on each side from verses 7–9 and 16–18 of Mark 1. Lines of writing preserved on each side indicate that this fragment comes from the bottom of the first written page of a codex—a book rather than a scroll. The text does not present any surprising readings for a manuscript of its age, and the codex format is also what we would expect.

Even though it is not quite so early as many hoped, P137 is still a significant find. Its date range makes it likely the earliest copy of Mark’s gospel. The fact that the text presents us with no new variants is partially a reflection of the overall stability of the New Testament text over time. Moreover, P137 is not the only new papyrus of the New Testament to be published in the latest Oxyrhynchus volume. Also published are P138, a third-century papyrus of Luke 13:13–17 and 13:25–30, and P139, a fourth-century papyrus of Philemon 6–8 and 18–20. P138 overlaps with two roughly contemporary manuscripts of Luke, which allows us better opportunity to assess the early transmission of Luke’s gospel. Additionally, early manuscripts of Philemon are rare, and P139 is among the earliest.

It should be stated, however, that we have no shortage of New Testament manuscripts. There are about 5,300 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament of various sizes and dates. Such an “embarrassment of riches,” as they have been called, allows us to reconstruct the original text of the New Testament with a high degree of confidence. As exciting as they are, textually speaking, new manuscript discoveries tend to confirm or at most fine-tune our Greek New Testament editions. As an example, our Greek New Testaments would be exactly the same with or without our current earliest New Testament manuscript, P52.

Questions Remain

One lingering question is whether or not the new Mark fragment was ever up for sale. The EES, which owns the papyrus, emphatically denies that they ever attempted to sell it. Yet, Scott Carroll and others have reported that it was indeed offered for sale. In a comment on the post that broke the news about the EES publication at the blog Evangelical Textual Criticism, someone commenting as Carroll named Dirk Obbink as the one who offered the papyrus to him. Obbink was formerly editor of the Oxyrhynchus collection, and Carroll was involved in acquisitions for the Green family at the time. Some of that collection later became part of the Museum of the Bible collection.

Many people—including Carroll himself—believed that the Greens had at some point purchased the manuscript until it appeared in an Oxyrhynchus volume. Obbink recently denied attempting to sell the manuscript to the Greens, according to Candida Moss and Joel Baden, writing for The Daily Beast. When I contacted Carroll and Obbink for statements, Carroll replied that he had nothing to add to or subtract from his story, and Obbink did not respond.

This new publication is only the first word on the manuscript. There is surely much more to come. Manuscript dates are often disputed, though I expect the question will be whether P137 could be later, not whether it could be earlier. Multi-spectral imaging and digital image processing open new doors to deciphering and understanding manuscripts, and P137 might benefit from such types of analysis.

Rather than disappointment that P137 is not quite as early as once thought, the publication of P137 is a cause to celebrate. We have another significant find, and it is the earliest manuscript of Mark 1! The excavations of Oxyrhynchus continue to yield valuable artifacts of antiquity including new biblical manuscripts after over a century of publishing. We can happily look forward to more unknown treasures yet to come.

The EES has made the publication, including images of P137, available here.

Elijah Hixson is an adjunct lecturer at Edinburgh Bible College. He has written articles for academic journals and is a regular contributor to the Evangelical Textual Criticism blog.

* Artigo reproduzido na íntegra

Veja também:

‘First-Century’ Mark Fragment: Second Update – On 11 June 2018 – By Daniel B. Wallace

Update on P137 (P.Oxy. 83.5345) – By Elijah Hixson: Evangelical Textual Criticism – June 11, 2018

“First Century” Mark and “Second Century” Romans and “Second Century” Hebrews and “Second Century” 1 Corinthians – By Brent Nongbri: Variant Readings – June 12, 2018

Leia Mais:

Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts

“First-Century Mark,” Published at Last? [Updated]