De repente, meus alunos encontraram duas versões da parábola dos dois filhos de Mt 21, 28-32. Examinamos a questão na sala de aula. Descobrimos que há três leituras possíveis para esta parábola.

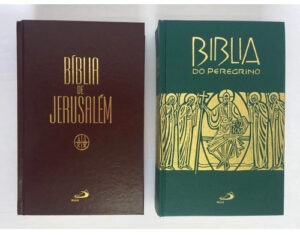

:. Diz o texto da Bíblia de Jerusalém (São Paulo: Paulus, 2002):

28“Que vos parece? Um homem tinha dois filhos. Dirigindo-se ao primeiro, disse: ‘Filho, vai trabalhar hoje na vinha’. 29Ele respondeu: ‘Não quero’; mas depois, pego pelo remorso, foi. 30Dirigindo-se ao segundo, disse a mesma coisa. Este respondeu: ‘Eu irei, senhor’; mas não foi. 31Qual dos dois realizou a vontade do pai?” Responderam-lhe: “O primeiro”. Então Jesus lhes disse: “Em verdade vos digo que os publicanos e as prostitutas vos precederão no Reino de Deus. 32Pois João veio a vós, num caminho de justiça, e não crestes nele. Os publicanos e as prostitutas creram nele. Vós, porém, vendo isso nem sequer tivestes remorso para crer nele.

:. Diz o texto da Bíblia do Peregrino (São Paulo: Paulus, 2002):

28 Que vos parece? Um homem tinha dois filhos. Dirigiu-se ao primeiro: Filho, vai hoje trabalhar na minha vinha.

29Repondeu-lhe: Sim, senhor. Mas não foi. 30Depois foi dizer o mesmo ao segundo. Este respondeu: Não quero. Mas logo se arrependeu e foi. 31Qual dos dois cumpriu a vontade de seu pai?

Dizem-lhe:

– O último.

E Jesus lhes diz:

-Eu vos asseguro que os coletores e as prostitutas entrarão antes de vós no reino de Deus. 32Porque veio João, ensinando o caminho da honradez, e não crestes nele, ao passo que os coletores e as prostitutas creram. E vós, mesmo depois de ver isso, não vos arrependestes nem crestes nele.

Nos versículos 29 e 30 a ordem das repostas está invertida nos dois textos:

Bíblia de Jerusalém: o primeiro filho disse não, mas foi; o segundo filho disse sim, mas não foi. Quem realizou a vontade do pai? O primeiro.

Bíblia do Peregrino: o primeiro filho disse sim, mas não foi; o segundo filho disse não, mas foi. Quem realizou a vontade do pai? O último.

Explica Bruce M. Metzger em A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft/United Bible Societies, 2. ed., 2006:

A transmissão textual da parábola dos dois filhos é muito confusa.

A transmissão textual da parábola dos dois filhos é muito confusa.

O filho que recusa, mas que depois obedece, é mencionado em primeiro ou em segundo lugar?

Qual dos dois filhos os judeus pretendiam afirmar ter cumprido a ordem do pai e que palavra eles usaram em sua resposta à pergunta de Jesus (πρῶτος ou ἔσχατος ou ὕστερος ou δεύτερος)?

Existem três formas principais de texto:

(a) De acordo com א [Sinaiticus] C* [Ephraemi Rescriptus] K W Δ II itc.q vg syrc.p.h al, o primeiro filho diz “não”, mas depois se arrepende e vai. O segundo filho diz “sim”, mas não faz nada. Qual deles fez a vontade do pai? Resposta: ὁ πρῶτος [o primeiro].

(b) De acordo com D [Bezae Cantabrigiensis] ita.b.d.e.ff2.h.l syrs al, o primeiro filho diz “não”, mas depois se arrepende e vai. O segundo filho diz “sim”, mas não faz nada. Qual deles fez a vontade do pai? Resposta: ὁ ἔσχατος [o último].

(c) De acordo com B [Vaticanus] Θ, f13 700 syrpal arm geo al, o primeiro filho diz “sim”, mas não faz nada. O segundo diz “não”, mas depois se arrepende e vai. Qual deles fez a vontade do pai? Resposta: ὁ ὕστερος (B) [o último], ou ὁ ἔσχατος (© [12 700 arm) [o último], ou ὁ δεύτερος (4 273) [o segundo], ou ὁ πρῶτος (geo*) [o primeiro].

Como (b) é a mais difícil das três formas de texto, vários estudiosos (Lachmann, Merx, Wellhausen, Hirsch) pensaram que ela deve ser preferida, explicando as outras duas como correções inseridas pelos copistas para dar maior coerência ao texto.

Mas (b) não é apenas difícil, é absurda – o filho que diz “sim”, mas não faz nada, é quem obedece à vontade do pai?

Jerônimo, que conhecia, em sua época, manuscritos que continham respostas absurdas, sugeriu que, por meio da perversidade, os judeus deram intencionalmente uma resposta absurda, a fim de estragar o sentido da parábola.

Mas esta explicação requer a suposição adicional de que os judeus não só reconheceram que a parábola era dirigida contra eles próprios, mas escolheram dar uma resposta absurda em vez de simplesmente permanecerem em silêncio.

Como tais explicações atribuem aos judeus, ou a Mateus, motivos psicológicos rebuscados ou literários, excessivamente sutis, o Comitê julgou que a origem da leitura (b) se deve a copistas que, ou cometeram um erro de transcrição, ou que foram motivados por tendências antifarisaicas (ou seja, visto que Jesus caracterizou os fariseus como aqueles que dizem, mas não praticam, eles devem ser representados como aprovadores do filho que disse “eu vou” e não foi).

Deste modo, ficamos com as leituras (a) e (c), sendo a leitura (a), mais provavelmente, a original.

Não só os testemunhos que apoiam (a) são ligeiramente melhores do que aqueles que leem (c), mas haveria uma tendência natural para transpor a ordem de (a) para a de (c) porque:

(1) poderia argumentar-se que se o primeiro filho obedecesse, não havia razão para convocar o segundo

(2) era natural identificar o filho desobediente com os judeus em geral ou com os principais sacerdotes e anciãos (v. 23) e o filho obediente com os gentios ou com os cobradores de impostos e as prostitutas (v. 31) – e de acordo com qualquer uma das linhas de interpretação, o filho obediente deveria vir por último na sequência cronológica.

Também pode ser observado que a inferioridade da forma (c) é demonstrada pela grande diversidade de leituras no final da parábola.

B. M. Metzger classifica os textos analisados nesta obra com as letras A, B, C e D entre colchetes. Este texto da parábola dos dois filhos está classificado como {C}.

O que significa isso?

{A} significa que o texto é confiável

{B} significa que o texto é quase certo

{C} indica que o Comitê** teve dificuldades para decidir qual variante deveria aparecer no texto

{D} que raramente aparece, indica que o Comitê teve muitas dificuldades para chegar a uma decisão.

** O Comitê responsável pela edição de The Greek New Testament, Fourth Revised Edition. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft/United Bible Societies, 1994 era composto por Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini e Bruce M. Metzger.

Roger L. Omanson, Variantes textuais do Novo Testamento: Análise e avaliação do Aparato Crítico de “O Novo Testamento Grego” . Barueri: Sociedade Bíblica do Brasil, 2010, que é uma versão simplificada do comentário de Bruce M. Metzger, diz:

Nesses três versículos [Mt 21,29-31], há muitas diferenças entre os manuscritos, sendo que as principais delas são as seguintes:

(1) Em alguns manuscritos, o primeiro filho diz “Não”, mas depois se arrepende e vai trabalhar na vinha. O segundo filho diz “Sim”, mas não vai trabalhar. A pergunta que é feita é esta: “Qual dos dois fez a vontade do pai”? A resposta é: “o primeiro”.

Esta leitura, adotada por quase todas as traduções, tem tudo para ser original, pelas seguintes razões:

(a) Faz sentido que, no momento em que o primeiro filho disse “não”, o pai tenha pedido ao segundo filho para que fosse.

(b) Essa leitura tem um apoio de manuscritos levemente superior ao das outras variantes.

(2) Em alguns outros manuscritos, o primeiro filho diz “sim”, mas depois se recusa a ir trabalhar na vinha. O segundo filho diz “não”, mas posteriormente se arrepende e vai trabalhar. “Qual dos dois fez a vontade do pai”? Esses manuscritos têm as seguintes respostas diferentes: “O último” (ὁ ὕστερος), “O último” (ὁ ἔσχατος), “O segundo” (ὁ δεύτερος), e “O primeiro” (ὁ πρῶτος).

Entretanto, esta leitura não faz tanto sentido quanto a anterior, apresentada acima (a leitura 1). Se o primeiro filho disse “sim”, não haveria por que o pai solicitar ao segundo filho que fosse trabalhar.

Entretanto, esta leitura não faz tanto sentido quanto a anterior, apresentada acima (a leitura 1). Se o primeiro filho disse “sim”, não haveria por que o pai solicitar ao segundo filho que fosse trabalhar.

Provavelmente, esta leitura reflete o esforço dos copistas para fazer com que a ordem cronológica, no texto, coincidisse com os acontecimentos históricos.

Em outras palavras, o primeiro filho é visto com o representante dos judeus em geral, ou, mais diretamente, dos principais sacerdotes e anciãos (v. 23) e o segundo filho é visto como sendo os gentios ou os cobradores de impostos e as prostitutas (v. 31).

(3) Em alguns outros manuscritos, o primeiro filho diz “não”, mas depois se arrepende e vai trabalhar na vinha. O segundo filho diz “sim”, mas não vai trabalhar. “Qual dos dois fez a vontade do pai”? A resposta é: “o último”.

Alguns intérpretes entendem que, por ser a mais difícil, esta leitura é a original, e que os copistas teriam alterado o texto para as formulações que aparecem em (1) e (2).

Entretanto, esta leitura é tão difícil que, no contexto, não faz sentido nenhum.

Bibliografia

Centro para o estudo dos manuscritos do Novo Testamento. Post publicado no Observatório Bíblico em 22.03.2006.

KONINGS, J. Traduções bíblicas católicas no Brasil (2000-2015). Revista Pistis & Praxis, 8(1), p. 89–102, 2016.

Lista de manuscritos unciais do Novo Testamento – Wikipedia.

METZGER, B. M. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft/United Bible Societies, 2. ed., 2006 [existe uma versão em espanhol].

OMANSON, R. L. Variantes textuais do Novo Testamento: Análise e avaliação do Aparato Crítico de “O Novo Testamento Grego” . Barueri: Sociedade Bíblica do Brasil, 2010.