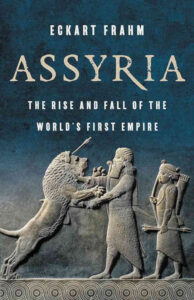

FRAHM, E. Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Empire. London: Bloomsbury, 2023, 528 p. – ISBN 9781541674400.

Diz a editora:

O primeiro relato magistral e abrangente de não-ficção sobre a ascensão e queda do que os historiadores consideram ser o primeiro império do mundo: a Assíria.

No seu auge, em 660 a.C., o reino da Assíria se estendia do Mar Mediterrâneo ao Golfo Pérsico. Foi o primeiro império que o mundo já viu.

Aqui, o assiriólogo Eckart Frahm conta a história épica da Assíria e seu papel formativo na história global. As amplas conquistas da Assíria são conhecidas há muito tempo pela Bíblia Hebraica e por relatos gregos posteriores. Mas quase dois séculos de investigação permitem agora uma rica imagem dos assírios e do seu império para além do campo de batalha: as suas vastas bibliotecas e esculturas monumentais, as suas elaboradas redes comerciais e de informação, e o papel crucial desempenhado pelas mulheres reais.

Embora a Assíria tenha sido esmagada por potências emergentes no final do século VII a.C., o seu legado perdurou desde os impérios babilônico e persa até Roma e mais além. A Assíria é um relato impressionante e confiável de uma civilização essencial para a compreensão do mundo antigo e do nosso.

Eckart Frahm é professor de assiriologia no departamento de línguas e civilizações do antigo Oriente Médio na Universidade de Yale, USA. Um dos maiores especialistas mundiais no Império Assírio, ele é autor ou coautor de seis livros sobre a história e a cultura da antiga Mesopotâmia.

The masterful first comprehensive non-fiction account of the rise and fall of what historians consider to be the world’s very first empire: Assyria.

At its height in 660 BCE, the kingdom of Assyria stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf. It was the first empire the world had ever seen.

Here, historian Eckart Frahm tells the epic story of Assyria and its formative role in global history. Assyria’s wide-ranging conquests have long been known from the Hebrew Bible and later Greek accounts. But nearly two centuries of research now permit a rich picture of the Assyrians and their empire beyond the battlefield: their vast libraries and monumental sculptures, their elaborate trade and information networks, and the crucial role played by royal women.

Although Assyria was crushed by rising powers in the late seventh century BCE, its legacy endured from the Babylonian and Persian empires to Rome and beyond. Assyria is a stunning and authoritative account of a civilisation essential to understanding the ancient world and our own.

Eckart Frahm is professor of Assyriology in the department of Near Eastern languages and civilisations at Yale. One of the world’s foremost experts on the Assyrian Empire, he is the author or co-author of six books on ancient Mesopotamian history and culture. He lives in New Haven, Connecticut.

Eckart Frahm (* 25. Februar 1967) ist ein deutscher Altorientalist und seit 2008 Professor an der Yale University. Frahm wurde 1996 an der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen promoviert und habilitierte sich 2007 an der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg unter Stefan Maul. Seine Forschungsschwerpunkte sind assyrische und babylonische Geschichte sowie mesopotamische Gelehrtentexte aus dem letzten vorchristlichen Jahrtausend.

Transcrevo trechos da Introdução:

A queda da Assíria ocorreu muito antes de alguns impérios mais conhecidos do mundo antigo serem fundados: o Império Persa, estabelecido em 539 a.C. por Ciro II; O Império Greco-Asiático de Alexandre, o Grande, do século IV a.C., e seus estados sucessores; os impérios do terceiro século a.C. criados pelo governante indiano Ashoka e pelo imperador chinês Qin Shi Huang; e o mais proeminente e influente deles, o Império Romano, cujo início ocorreu no primeiro século a.C. O reino assírio pode não ter o mesmo reconhecimento. Mas durante mais de cem anos, de cerca de 730 a 620 a.C., foi um corpo político tão grande e tão poderoso que pode ser justamente chamado de primeiro império do mundo.

E por isso a Assíria é importante. A “história mundial” não começa com os gregos ou os romanos — começa com a Assíria. As burocracias, as redes de comunicação e os modos de dominação criados pelas elites assírias há mais de 2700 anos serviram de modelo para muitas das instituições políticas das grandes potências subsequentes, primeiro diretamente e depois indiretamente, até aos dias de hoje. Este livro conta a história da lenta ascensão e dos dias de glória desta notável civilização antiga, da sua queda dramática e da sua intrigante vida após a morte.

A “verdadeira” Assíria — em vez da imagem distorcida que a Bíblia e os textos clássicos transmitiam dela — começou a recuperar seu lugar na consciência histórica do mundo moderno em 5 de abril de 1843, quando um francês de quarenta e um anos de idade, chamado Paul-Émile Botta, sentou-se à sua mesa na cidade de Mossul para escrever uma carta. Botta era cônsul francês em Mossul, na época uma remota cidade provincial do Império Otomano, mas a sua carta não era sobre política. Dirigido ao secretário da Société Asiatique de Paris, tratava de um espetacular achado arqueológico. Nos dias anteriores, revelou Botta, alguns de seus trabalhadores desenterraram vários baixos-relevos e inscrições estranhas e intrigantes perto da pequena vila de Khorsabad, cerca de 25 quilômetros a nordeste de Mossul. No final da sua carta, Botta anunciou com orgulho: “Acredito ser o primeiro a descobrir esculturas que podem ser consideradas pertencentes à época em que Nínive ainda estava florescendo”.

Durante o final da década de 1840 e início da década de 1850, enquanto prosseguiam as escavações em Khorsabad, Nimrud e Nínive, vários estudiosos na Grã-Bretanha e na França começaram a estudar a estranha escrita encontrada nos ortóstatos, touros colossais e tabuinhas de argila que haviam sido descobertas nestes sítios. Devido ao formato de cunha dos elementos básicos dos sinais individuais, a escrita ficou conhecida como cuneiforme, da palavra latina cuneus, que significa “cunha”. Não apenas a escrita, mas também a linguagem desses textos era desconhecida, o que tornava sua decifração extremamente desafiadora.

A decifração bem sucedida, tal como a descodificação dos hieróglifos egípcios cerca de trinta anos antes, abriu janelas para um passado que até então tinha sido quase inteiramente ficado em segredo — e preparou assim o cenário para nada menos do que um “segundo Renascimento”. Enquanto o primeiro, o Renascimento Europeu dos séculos XV e XVI, trouxe de volta as civilizações dos gregos e dos romanos, o novo Renascimento agora iniciado por Champollion e Hincks permitiu uma visão profunda dos mundos pré-clássicos do Egito e do antigo Oriente Médio e o acesso ao que foi apropriadamente chamado de “a primeira metade da história”.

As tabuinhas das bibliotecas de Assurbanípal forneceram insights altamente inesperados sobre as tradições intelectuais, literárias e religiosas da Assíria. Uma das primeiras descobertas espetaculares foi feita por um jovem estudioso autodidata chamado George Smith. No final do século XIX, escavadores e filólogos, alguns deles detentores de cátedras universitárias recentemente criadas, tinham estabelecido uma imagem da Assíria que incluía numerosos detalhes não conhecidos nem da Bíblia nem de fontes clássicas.

Novas descobertas feitas nos séculos XX e XXI modificaram e melhoraram significativamente a compreensão moderna da civilização assíria, especialmente no que diz respeito às suas origens e história antiga.

O estudo da Assíria já dura mais de 175 anos, durante os quais numerosas vozes assírias do passado começaram a falar novamente. Outras poderão ser trazidos de volta à vida no futuro, embora muitas mais permanecerão para sempre em silêncio. Certamente novas descobertas e novas análises das evidências disponíveis exigirão, sem dúvida, reavaliações futuras, mas, ao mesmo tempo, nos familiarizamos com cidades, reis e instituições políticas e sociais assírias sobre as quais nenhum autor bíblico ou clássico tinha qualquer pista , e provavelmente estamos mais bem informados sobre o início da civilização assíria do que os próprios assírios do período imperial.

A civilização assíria que conhecemos é marcada por uma mistura complexa de continuidade e mudança, à medida que lutou – muitas vezes com mais sucesso do que os reinos vizinhos – com grandes desafios históricos, desde ataques de potências estrangeiras a mudanças nos padrões climáticos até grandes mudanças culturais. Durante um período de cerca de 1.400 anos, até a sua rápida queda no final do século VII a.C., o Estado assírio conseguiu preservar e cultivar uma identidade específica, ao mesmo tempo que se reinventava, muitas vezes, e se adaptava a circunstâncias em constante mudança.

Séculos anteriores acreditavam que a Assíria representava um “outro” bárbaro. Mas esta antiga civilização tem, na verdade, muito mais em comum conosco do que se possa imaginar.

A Assíria produziu muitas características que, para o bem ou para o mal, ainda podem ser encontradas no mundo moderno: desde o comércio de longa distância, sofisticadas redes de comunicação e a promoção da literatura, da ciência e das artes patrocinada pelo Estado até deportações em massa, a utilização da violência extrema contra países inimigos e o uso generalizado de vigilância política a nível interno.

Novas investigações mostraram que a Assíria foi afetada, tal como nós, pela eclosão de pandemias e pelas vicissitudes das alterações climáticas, e pela forma como os seus governantes reagiram a estes desafios.

A Assíria, em outras palavras, tem muito a nos ensinar. E o momento parece oportuno para olharmos de novo para este antigo Estado, que durante o seu apogeu se transformou no primeiro império do mundo.

Assyria’s fall occurred long before some better-known empires of the ancient world were founded: the Persian Empire, established in 539 BCE by Cyrus II; Alexander the Great’s fourth-century BCE Greco-Asian Empire and its successor states; the third-century BCE empires created by the Indian ruler Ashoka and the Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang; and the most prominent and influential of these, the Roman Empire, whose beginnings lay in the first century BCE. The Assyrian kingdom may not have the same name recognition. But for more than one hundred years, from about 730 to 620 BCE, it had been a political body so large and so powerful that it can rightly be called the world’s first empire.

And so Assyria matters. “World history” does not begin with the Greeks or the Romans—it begins with Assyria. “World religion” took off in Assyria’s imperial periphery. Assyria’s fall was the result of a first “world war.” And the bureaucracies, communication networks, and modes of domination created by the Assyrian elites more than 2,700 years ago served as blueprints for many of the political institutions of subsequent great powers, first directly and then indirectly, up until the present day. This book tells the story of the slow rise and glory days of this remarkable ancient civilization, of its dramatic fall, and its intriguing afterlife.

And so Assyria matters. “World history” does not begin with the Greeks or the Romans—it begins with Assyria. “World religion” took off in Assyria’s imperial periphery. Assyria’s fall was the result of a first “world war.” And the bureaucracies, communication networks, and modes of domination created by the Assyrian elites more than 2,700 years ago served as blueprints for many of the political institutions of subsequent great powers, first directly and then indirectly, up until the present day. This book tells the story of the slow rise and glory days of this remarkable ancient civilization, of its dramatic fall, and its intriguing afterlife.

The “real” Assyria—rather than the distorted image the Bible and the classical texts conveyed of it—began to regain its place in the historical consciousness of the modern world on April 5, 1843, when a forty-one-year-old Frenchman by the name of Paul-Émile Botta sat down at his desk in the city of Mosul to write a letter. Botta was the French consul in Mosul, at the time a remote provincial town on the outskirts of the Ottoman Empire, but his letter was not about politics. Addressed to the secretary of the Société Asiatique in Paris, it was about a spectacular archaeological find. During the previous days, Botta revealed, some of his workmen had dug up several strange and intriguing bas-reliefs and inscriptions near the small vil-lage of Khorsabad, some 25 kilometers (15 miles) northeast of Mosul. At the end of his letter, Botta proudly announced, “I believe I am the first to discover sculptures that may be assumed to belong to the time when Nineveh was still flourishing.”

During the late 1840s a nd early 1850s, while the excavations at Khorsabad, Nimrud, and Nineveh went on, several scholars in Britain and France began to study the strange writing found on the orthostats, bull colossi, and clay objects that had come to light at these sites. Because of the wedge-shaped nature of the basic elements of individual signs, the script became known as cuneiform, from the Latin word cuneus, which means “nail” or “wedge.” Not only the script but also the language of these texts was unknown, which made their decipherment extremely challenging.

The successful decipherment, much like the decoding of Egyptian hieroglyphs some thirty years earlier, opened windows into a past that had been hitherto almost entirely veiled in secrecy—and thus set the stage for nothing less than a “second Renaissance.” Whereas the first, the European Renaissance of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, had brought back the civilizations of the Greeks and the Romans, the new Renaissance now initiated by Champollion and Hincks allowed deep insights into the preclassical worlds of Egypt and the ancient Near East—and access to what has been aptly called “the first half of history.”

The tablets from Ashurbanipal’s libraries provided highly unexpected insights into Assyria’s intellectual, literary, and religious traditions. One of the most spectacular early discoveries was made by a self-taught young scholar by the name of George Smith

By the end of the nineteenth century, excavators and philologists, some of them holders of newly created university chairs, had established an image of Assyria that included numerous details known neither from the Bible nor from classical sources.

New discoveries made in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have significantly modified and enhanced the modern understanding of Assyrian civilization, especially with regard to its origins and early history.

The study of Assyria has gone on for more than 175 years, during which numerous Assyrian voices from the past have begunto speak again. Others may be brought back to life in the future, though many more will remain forever silent. To be sure, new discoveries and fresh analyses of the available evidence will undoubtedly require future reassessments, but at the same time, we have become familiar with Assyrian cities, kings, and political and social institutions about which no biblical or classical author had any clue, and we are probably better informed about the beginnings of Assyrian civilization than were the Assyrians of the imperial period themselves.

The Assyrian civilization we have come to know is one marked by a complex mix of continuity and change, as it wrestled—often more successfully than neighboring kingdoms—with major historical challenges, from attacks by foreign powers to changes in rainfall patterns to major cultural shifts. Over a period of some 1,400 years, until its rapid fall in the late seventh century BCE, the Assyrian state managed to preserve and cultivate a particular identity while at the same time reinventing itself time and again and adapting to ever-changing circumstances.

Earlier centuries believed that Assyria represented a barbaric other. But this ancient civilization has actually much more in common with us than one might think. Assyria produced many features that, for better or worse, are still to be found in the modern world: from long-distance trade, sophisticated communication networks, and the state-sponsored promotion of literature, science, and the arts to mass deportations, the practice of engaging in extreme violence in enemy countries, and the widespread use of political surveillance at home. New research has shown that Assyria was affected, much as we are, by the outbreak of pandemics and the vicissitudes of climate change, and by how its rulers reacted to these challenges. Assyria, in other words, has much to teach us—and the time seems ripe to take a new look at this ancient state, which during its heyday morphed into the world’s first empire.