DOZEMAN, T. B. Joshua 1-12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015, 600 p. – ISBN 9780300149753.

Explica Thomas B. Dozeman, nas páginas 8-9:

O século XX viu o surgimento de um crescente interesse pela exploração física da Palestina. Os trabalhos de C. Ritter e de E. Robinson, já no século XIX, refletem o crescente interesse dos estudiosos bíblicos na geografia física da Palestina como um recurso para interpretar a literatura bíblica.

crescente interesse dos estudiosos bíblicos na geografia física da Palestina como um recurso para interpretar a literatura bíblica.

Assim, no início do século XX, o meio ambiente e a geografia física da Palestina foram firmemente estabelecidos como ferramentas importantes para a interpretação do livro de Josué.

Institutos arqueológicos da França, Alemanha, Estados Unidos e Reino Unido foram criados para apoiar o novo foco de pesquisa: École biblique et archéologique française de Jérusalem (EBAF) em 1890; Deutsche Evangelische Institut für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes (DEI) em 1900; American Society of Overseas Research (ASOR) em 1900; Kenyon Institute (KI) em 1919.

E deste modo o estudo da geografia e da arqueologia redirecionou a pesquisa da redação do livro de Josué para a história do Israel tribal.

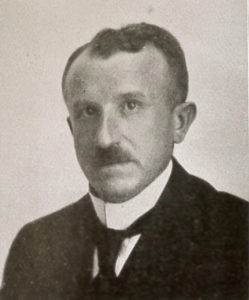

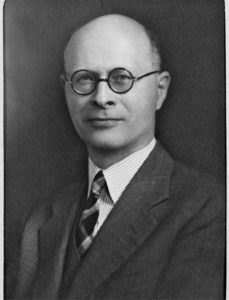

As pesquisas de Albrecht Alt (1883–1956) e de William Foxwell Albright (1891-1971) ilustram a mudança na metodologia da interpretação de Josué. Ambos estiveram na vanguarda da criação das novas disciplinas de geografia histórica e arqueologia. Alt era o diretor do Deutsche Evangelische Institut für Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes (DEI) em 1920, e ele continuou a liderar pesquisas na Síria-Palestina ao longo de toda a sua carreira. Albright foi o diretor da American Society of Overseas Research (ASOR) em Jerusalém de 1922 a 1929 e novamente de 1933 a 1936, e ele continuou a liderar pesquisas arqueológicas ao longo de sua carreira.

Os dois estudiosos compartilhavam uma gama de interesses metodológicos, incluindo arqueologia, geografia histórica e o estudo de línguas e literatura do Antigo Oriente Médio, recursos utilizados para a interpretação da Bíblia Hebraica. Ambos usaram essas metodologias para obter uma nova visão da história do Israel tribal e das circunstâncias de seu surgimento na terra da Palestina. A busca para descobrir a história mais antiga de Israel mudou o foco do estudo de Josué, antes voltado para a identificação de fontes literárias na composição da obra, para o valor do livro como um recurso para a pesquisa histórica do período tribal no ambiente geográfico da Síria-Palestina.

Apesar do interesse comum em arqueologia e geografia histórica, Alt e Albright divergiram em sua avaliação do livro de Josué.

Alt concordou com a conclusão de Kuenen e Wellhausen de que o livro carecia de valor histórico. Mas ele também concluiu que a crítica literária era muito limitada à literatura e, portanto, não investigava as antigas tradições presentes no livro de Josué que podem fornecer uma visão sobre a história do Israel tribal. Em vista disso, Alt explorou as tradições etiológicas pré-literárias de Josué como uma janela para o período de colonização da terra. Ele concluiu que as tribos individuais se infiltraram lentamente na Palestina, conforme recontado na versão da conquista em Juízes 1.

Albright, por outro lado, era cético quanto à crítica literária e também rejeitou as conclusões histórico-críticas de Kuenen e Wellhausen de que o livro de Josué não tinha credibilidade histórica. Este ceticismo foi acoplado com a rejeição adicional da conclusão de Alt de que as histórias etiológicas pré-literárias revelam a mentalidade dos israelitas tribais, mas não relatam eventos históricos. Para Albright, o texto de Josué preservou a história. Em apoio a essa conclusão, ele se concentrou nas evidências arqueológicas e na literatura antiga para confirmar a confiabilidade histórica do relato da conquista em Josué como uma invasão única e unificada realizada por todas as tribos.

A “teoria da infiltração pacífica” de Alt e a “teoria da conquista unificada” de Albright levam a interpretações significativamente diferentes do livro de Josué, apesar da abordagem metodológica compartilhada do texto. O rápido acúmulo de novos insights sobre a formação do Israel tribal a partir da arqueologia e da geografia histórica durante o primeiro período do século XX é evidente nos escritos de ambos os estudiosos e seus artigos são frequentemente respostas às pesquisas emergentes do outro.

(…)

Continua Thomas B. Dozeman, nas páginas 13-14:

Alt e Albright compartilharam uma série de pressupostos metodológicos na interpretação do livro de Josué:

1. Os dois estudiosos enfatizaram o poder do ambiente social e físico da Palestina para interpretar o livro

2. Nenhum deles estava interessado na composição literária do livro nem em sua função dentro do contexto literário do Pentateuco ou dos Profetas anteriores

3. Ambos concordaram que o livro fornece uma visão sobre o mundo do Israel tribal e, portanto, tem valor histórico, embora de tipo diferente

4. Os dois assumiram que a etiologia é uma forma antiga de tradição oral que remonta ao período das tribos

5. Ambos reconstruíram a história do Israel tribal para ajustá-la à narrativa bíblica, na qual os israelitas não são nativos de Canaã.

Interpretações divergentes de etiologia e arqueologia, no entanto, levaram a visões contrastantes da entrada das tribos na Palestina, como vimos. A interpretação das etiologias indicou a Alt que grupos de tribos “se infiltraram” na Palestina ao longo do tempo, enquanto os vestígios arqueológicos de Albright apontavam, em vez disso, para uma conquista “unificada” do Israel tribal no século XIII a.C.

O “modelo da infiltração pacífica” e o “modelo da conquista unificada” dominaram a pesquisa sobre Josué ao longo do século XX.

Os arqueólogos da Síria-Palestina na primeira metade do século XX continuaram a julgar o relato da invasão e conquista de Canaã em Josué como histórico. Esses pesquisadores interpretaram Israel como um povo não indígena da terra de Canaã que experimentou um êxodo do Egito e uma subsequente conquista de Canaã durante o século XIII a.C. Além da pesquisa de Albright, as escavações de John e J. B. E. Garstang (1940), G. E. Wright (1940) e P. Lapp (1969) reforçaram a mesma conclusão. John Bright finalmente sintetizou a pesquisa arqueológica em uma história de Israel que foi baseada na conquista de Canaã (2000). O valor histórico do livro de Josué também foi mantido pelos primeiros arqueólogos israelenses, como Y. Yadin, que também identificou níveis de destruição em Hazor que pareciam confirmar o relato de uma invasão semelhante ao relato de Josué (1982).

A escola alemã continuou a fornecer uma contra-hipótese da origem de Israel baseada mais em um modelo antropológico, no qual clãs seminômades migraram para a região montanhosa de Canaã e se organizaram livremente em torno de centros de culto. A teoria da infiltração pacífica questionou a historicidade da conquista no livro de Josué. Ainda assim, alguns aspectos do livro mantiveram valor histórico, especialmente na teoria de que o Israel tribal era uma anfictionia, que Martin Noth desenvolveu com base no estudo social comparativo. Estruturas anfictiônicas eram características da liga de Delfos na Grécia, na qual doze grupos eram organizados em torno do santuário de Apolo. Noth viu a mesma estrutura e propósito para a organização das doze tribos em Gênesis 49 e Nm 26. Como resultado, embora rejeitasse a historicidade da conquista unificada de Canaã, Noth sustentava que as histórias de reuniões tribais em locais religiosos como Siquém em Js 8,30–35 e Josué 24 forneceram uma janela para o início da história de Israel. Desse modo, a metodologia da antropologia comparada revelou o valor histórico de aspectos do livro de Josué.

Pesquisas subsequentes em etiologia, arqueologia, antropologia e história cultural do Antigo Oriente Médio minaram lentamente os modelos de infiltração pacífica e conquista unificada para explicar as origens de Israel e, com eles, a interpretação de Josué como um recurso para recuperar a história do Israel tribal.

(…)

O impasse em recuperar a história da época tribal de Israel com o auxílio do livro de Josué redirecionou a pesquisa de volta à questão de sua composição literária (p. 16).

The research on the book of Joshua expands at the turn of the twentieth century from the literary focus of source criticism to the broader study of the book as a resource for recovering the history of tribal Israel. The turn to history is fueled by the increasing exposure of scholars to the geography and physical environment of Syria-Palestine. The work of C. Ritter (1866) on the geography of Sinai, Palestine, and Syria from 1848 through 1855 and E. Robinson’s summary of travel in Palestine in 1865, Physical Geography of the Holy Land, refl ect the growing interest of biblical scholars in the environment of Palestine as a resource for interpreting biblical literature. By the early twentieth century, the environment and physical geography of Palestine were fi rmly established as an important tool for interpreting the book of Joshua. International archaeological institutes were formed to support the new research focus, including the French École Biblique, formed in 1890; the German Protestant Institute in 1900; the American School of Oriental Research in 1900; and the British School of Archaeology in 1919. The study of geography and archaeology redirected research from the late literary composition of Joshua to the history of tribal Israel.

The research of A. Alt (1883-1956) and W. F. Albright 1891-1971) illustrates the shift in methodology in the interpretation of Joshua. Both scholars were in the forefront of forging the new disciplines of historical geography and archaeology. Alt was the director of the German Evangelical Institute for Old Testament Research of the Holy Land in Jerusalem in 1920, and he continued to lead research in Syria-Palestine throughout his career, often serving as president of the German Association for Research of the Holy Land. Albright was the director of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem from1922 to1929 and again from 1933 to 1936, and he continued to lead archaeological research throughout his career. The two scholars shared a range of methodological interests, including archaeology, historical geography, and the study of ancient Near Eastern languages and literature, for interpreting the Hebrew Bible. Both used these methodologies to gain new insight into pre-Israelite history and the emergence of tribal Israel in the land of Palestine. The quest to uncover the earliest history of Israel changed the focus of the study of Joshua from the identification of late literary authors in source criticism to the value of the book as a resource for historical research of the tribal period within the geographical environment of Syria-Palestine.

The research of A. Alt (1883-1956) and W. F. Albright 1891-1971) illustrates the shift in methodology in the interpretation of Joshua. Both scholars were in the forefront of forging the new disciplines of historical geography and archaeology. Alt was the director of the German Evangelical Institute for Old Testament Research of the Holy Land in Jerusalem in 1920, and he continued to lead research in Syria-Palestine throughout his career, often serving as president of the German Association for Research of the Holy Land. Albright was the director of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem from1922 to1929 and again from 1933 to 1936, and he continued to lead archaeological research throughout his career. The two scholars shared a range of methodological interests, including archaeology, historical geography, and the study of ancient Near Eastern languages and literature, for interpreting the Hebrew Bible. Both used these methodologies to gain new insight into pre-Israelite history and the emergence of tribal Israel in the land of Palestine. The quest to uncover the earliest history of Israel changed the focus of the study of Joshua from the identification of late literary authors in source criticism to the value of the book as a resource for historical research of the tribal period within the geographical environment of Syria-Palestine.

Despite the shared interest in archaeology and historical geography, Alt and Albright diverged in their evaluation of the book of Joshua. Alt agreed with the conclusion of Kuenen and Wellhausen that the book lacked historical value. But he also concluded that source criticism was too narrowly limited to literature and thus did not probe the earliest traditions in the book of Joshua that may provide insight into the history of tribal Israel. In view of this, Alt explored the preliterary etiological traditions of Joshua as a window into the period of the settlement of the land. He concluded that the individual tribes slowly infiltrated Palestine, as recounted in the version of the conquest in Judg 1. Albright, on the other hand, was skeptical of source criticism and also rejected the historical-critical conclusions of Kuenen and Wellhausen that the book of Joshua lacked historical credibility. Th is skepticism was coupled with the further rejection of Alt’s conclusion that the preliterary etiological stories reveal the mentality of tribal Israelites but do not report historical events. For Albright, the text of Joshua preserved history. In support of this conclusion, he focused on archaeological evidence and ancient literature to confirm the historical reliability of the account of the conquest in Joshua as a single unified invasion by all of the tribes.

The “infiltration theory” of Alt and the “unified conquest theory” of Albright lead to significantly diff erent interpretations of the book of Joshua, despite the shared methodological approach to the text. The rapid accumulation of new insights into the formation of tribal Israel from archaeology and historical geography during the early period of the twentieth century is evident in the writing of both scholars; their articles are often responses to the other’s emerging research. A review of the exchange illustrates the two research paradigms that most infl uence the interpretation of the book of Joshua throughout the twentieth century and continue to capture the imagination of scholars today.

(…)

Continues Thomas B. Dozeman, on pages 13-14:

Alt and Albright shared a number of methodological presuppositions in the interpretation of the book of Joshua: (1) Both scholars emphasized the power of the social and physical environment of Palestine for interpreting the book; (2) neither was interested in the literary composition of the book nor in its function within the literary context of the Pentateuch or the Former Prophets; (3) both agreed that the book provided insight into the world of tribal Israel and therefore has historical value, albeit of different kinds; (4) each assumed that etiology is an ancient form of oral tradition that reaches back to the period of the tribes; and (5) both reconstructed the history of tribal Israel to conform with the biblical narrative, in which the Israelites are not indigenous to the promised land. Divergent interpretations of etiology and archaeology, however, led to contrasting views of the entry of the tribes into the promised land, as we have seen: The isolation of individual etiologies as the object of interpretation indicated to Alt that groups of tribes “infiltrated” the promised land over time; while the archaeological remains for Albright pointed instead to a “unified” conquest of tribal Israel in the thirteenth century BCE.

The “infiltration model” and the “unified conquest model” dominated the research on Joshua throughout the twentieth century. The archaeologists of Syria-Palestine in the first half of the twentieth century continued to judge the account of the invasion and conquest of Canaan in Joshua to be historical. These researchers interpreted Israel to be a nonindigenous people to the land of Canaan who experienced an exodus from Egypt and a subsequent conquest of Canaan during the thirteenth century BCE. In addition to the research of Albright, excavations by J. and J. B. E. Garstang (1940), G. E. Wright (1940), and P. Lapp (1969) reinforced the same conclusion. J. Bright eventually synthesized the archaeological research into a history of Israel that was grounded in a conquest of Canaan (2000). The historical value of the book of Joshua was also maintained by early Israeli archaeologists, such as Y. Yadin, who also identified destruction levels at Hazor that appeared to confirm the account of a war of invasion similar to the account in Joshua (1982).

The German school continued to provide a counterhypothesis of the origin of Israel based more on an anthropological model, in which seminomadic clans migrated into the hill country of Canaan and were organized loosely around cultic centers. The infiltration theory called into question the historicity of the conquest in the book of Joshua; yet aspects of the book retained historical value, especially in the theory that tribal Israel was an amphictyony, which Noth developed on the basis of comparative social study (1930;1960: 85–97). Amphictyonic structures were characteristic of the Delphic league in Greece, in which twelve groups were organized around the sanctuary of Apollo. Noth discerned the same structure and purpose to the organization of the twelve tribes in Gen 49 and Num 26. As a result, even though he rejected the historicity of the unified conquest of Canaan, Noth maintained that the stories of tribal gatherings at religious sites such as Shechem in Josh 8:30–35 and Josh 24 provided a window into the early history of Israel. In this way, the methodology of comparative anthropology revealed the historical value of aspects of the book of Joshua.

Subsequent research in etiology, archaeology, anthropology, and ancient Near Eastern cultural history has slowly eroded both the infiltration and the unified conquest models of the origins of tribal Israel and with them the interpretation of Joshua as a resource for recovering the history of tribal Israel. K. W. Whitelam provides the most thorough summary of the presuppositions of Alt and Albright that supported their reconstruction of the tribal period (1996: 37-121). The following is an abridged summary

focused on the problems that infl uence the interpretation of Joshua.

(…)

The impasse in recovering the history of the tribal period from the book of Joshua has redirected research back to the question of its literary composition (p. 16).