Estou lendo trechos do livro de KALIMI, I. ; RICHARDSON, S. (eds.) Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill, 2014, XII + 548 p. – ISBN 9789004265615.

Estou lendo trechos do livro de KALIMI, I. ; RICHARDSON, S. (eds.) Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill, 2014, XII + 548 p. – ISBN 9789004265615.

Resumi os pontos principais do capítulo 4 sobre a tomada de Laquis.

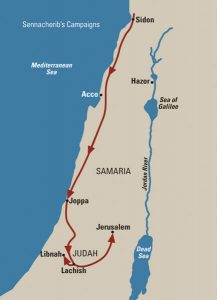

1. Laquis na época da campanha de Senaquerib

2. O ataque assírio a Laquis

Nas páginas 85-89, diz David Ussishkin:

Os relevos de Laquis

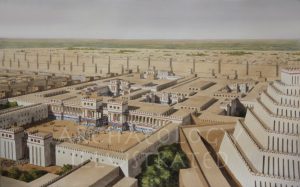

Alguns anos após o controle de Judá, Senaquerib construiu seu palácio real em Nínive, hoje conhecido como Palácio do Sudoeste. Esse edifício está registrado em detalhes nas inscrições de Senaquerib, que o chama de Palácio sem Rival. O palácio foi amplamente escavado na metade do século XIX pelo arqueólogo inglês Austen Henry Layard em nome do Museu Britânico em Londres. Ele fez uma planta do edifício e descobriu um grande número de relevos feitos de placas de alabastro que adornavam as paredes.

nas inscrições de Senaquerib, que o chama de Palácio sem Rival. O palácio foi amplamente escavado na metade do século XIX pelo arqueólogo inglês Austen Henry Layard em nome do Museu Britânico em Londres. Ele fez uma planta do edifício e descobriu um grande número de relevos feitos de placas de alabastro que adornavam as paredes.

As placas de alabastro que representam em relevo a conquista de Laquis foram dispostas nas paredes de uma sala especial localizada na parte de trás de uma suíte cerimonial central do palácio. Parece que toda a sala, e talvez também toda a suíte, pretendia comemorar a conquista de Judá e a vitória em Laquis. De acordo com a reconstrução de David Ussishkin, a “sala de Laquis”, rotulada por Layard “sala XXXVI”, tinha 11,5 metros de largura e 5 metros de comprimento. Suas paredes provavelmente estavam inteiramente cobertas pelos relevos de Laquis. Os relevos no lado esquerdo da sala foram deixados por Layard no local e foram perdidos, enquanto o restante da série, composto por doze placas, foi transferido por ele para o Museu Britânico em Londres e atualmente é exibido lá. O comprimento da série preservada é de cerca de 19 metros. Parece que a parte que faltava da série tinha cerca de 8 metros de comprimento. Consequentemente, a série original que descreve a conquista de Laquis deve ter cerca de 27 metros de comprimento. Esta é a série mais longa e detalhada de relevos assírios, representando o assalto e a conquista de uma única cidade fortaleza.

Os relevos ausentes não foram documentados, e a única dica sobre o seu conteúdo é a observação de Layard de que “consistiam de grandes formações de cavaleiros e quadrigários”. Mais adiante, da esquerda para a direita, são mostradas a infantaria, o assalto à cidade, a transferência do espólio, a punição de cativos, as famílias exiladas, Senaquerib sentado em seu trono, a tenda real e a carruagem e, finalmente, o acampamento assírio. Significativamente, a cena principal que retratava o assalto à cidade foi colocada exatamente no centro da parede do fundo da sala, em frente à entrada monumental. Dadas as boas condições de iluminação, qualquer um que passasse pela entrada podia ver o ataque de Laquis à sua frente quando entrasse na sala.

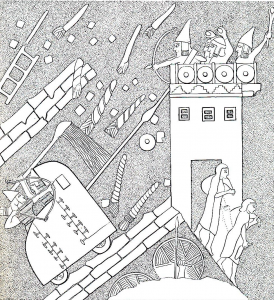

A porta da cidade é mostrada no centro da cena, retratando o assalto à cidade, sendo atacada por uma máquina de cerco. Refugiados são mostrados carregando seus pertences e saindo da cidade através da porta. Nos dois lados da cidade sitiada estão representadas as muralhas da cidade. Os soldados judaítas estão nas muralhas e balcões no topo da guarita e atiram nos assírios atacantes. A rampa de assédio é mostrada à direita da guarita. Como mencionado, sete máquinas de cerco, apoiadas por arqueiros e atiradores com fundas, estão atacando as muralhas – cinco no topo do rampa de assédio e duas na porta da cidade, possivelmente colocadas em uma rampa de assédio adicional construída contra a guarita. Relevos assírios geralmente retratam uma e, em alguns casos, duas máquinas de cerco atacando as muralhas de uma cidade sitiada. O relevo que representa o cerco de Laquis é único ao mostrar nada menos que sete máquinas de cerco participando ativamente da batalha.

A porta da cidade é mostrada no centro da cena, retratando o assalto à cidade, sendo atacada por uma máquina de cerco. Refugiados são mostrados carregando seus pertences e saindo da cidade através da porta. Nos dois lados da cidade sitiada estão representadas as muralhas da cidade. Os soldados judaítas estão nas muralhas e balcões no topo da guarita e atiram nos assírios atacantes. A rampa de assédio é mostrada à direita da guarita. Como mencionado, sete máquinas de cerco, apoiadas por arqueiros e atiradores com fundas, estão atacando as muralhas – cinco no topo do rampa de assédio e duas na porta da cidade, possivelmente colocadas em uma rampa de assédio adicional construída contra a guarita. Relevos assírios geralmente retratam uma e, em alguns casos, duas máquinas de cerco atacando as muralhas de uma cidade sitiada. O relevo que representa o cerco de Laquis é único ao mostrar nada menos que sete máquinas de cerco participando ativamente da batalha.

Mais à direita, são mostrados soldados assírios carregando o saque e prisioneiros, provavelmente oficiais de Ezequias, sendo severamente punidos, e os habitantes de Laquis deixando a cidade destruída. Os deportados levam seus pertences com eles, uma imagem trágica de famílias inteiras forçadas a sair de suas casas. A família mostrada aqui é composta por duas mulheres, seguidas por duas meninas e um homem que conduz um carro puxado por dois bois. O carro está carregado de utensílios domésticos e trouxas amarradas, nas quais duas crianças pequenas, um menino e uma menina, estão sentadas. As costelas dos bois aparecem destacadas, possivelmente para indicar que sofrem de desnutrição.

Os deportados se distinguem por sua aparência e vestuário, que provavelmente eram típicos do povo de Judá naquele período. As mulheres usam uma roupa longa e simples. Um longo xale cobre a cabeça, os ombros e as costas, chegando até a parte inferior do vestido. Os homens têm barba curta e suas cabeças estão enroladas em lenços com extremidades em franja. A roupa deles tem uma borla franjada pendurada entre as pernas. Homens e mulheres estão descalços.

A procissão dos soldados assírios carregando espólio, e a dos habitantes deportados, passa diante do rei assírio sentado em seu trono. A inscrição cuneiforme, gravada no fundo do relevo, identifica a cidade atacada como Laquis. O belo trono é ricamente ornamentado e é mencionado especificamente na inscrição. Quase certamente foi trazido da Assíria para Laquis para o uso de Senaquerib. O trono tem pernas muito altas, permitindo que o monarca sentado olhe de cima para as pessoas que estão à sua frente. Os pés do rei repousam sobre um escabelo alto. O trono e o escabelo eram decorados com marfim lindamente esculpido. Diante do rei está um alto oficial, possivelmente o comandante do exército (Tartan / turtanu). Ele é acompanhado por comandantes de menor patente, e dois eunucos segurando leques estão atrás do trono. Mais à direita, é mostrada a tenda real, identificada como a tenda de Senaquerib por uma curta inscrição cuneiforme, a carruagem cerimonial de Senaquerib, cavaleiros desmontados, o carro de batalha do rei e, finalmente, o acampamento fortificado assírio.

fundo do relevo, identifica a cidade atacada como Laquis. O belo trono é ricamente ornamentado e é mencionado especificamente na inscrição. Quase certamente foi trazido da Assíria para Laquis para o uso de Senaquerib. O trono tem pernas muito altas, permitindo que o monarca sentado olhe de cima para as pessoas que estão à sua frente. Os pés do rei repousam sobre um escabelo alto. O trono e o escabelo eram decorados com marfim lindamente esculpido. Diante do rei está um alto oficial, possivelmente o comandante do exército (Tartan / turtanu). Ele é acompanhado por comandantes de menor patente, e dois eunucos segurando leques estão atrás do trono. Mais à direita, é mostrada a tenda real, identificada como a tenda de Senaquerib por uma curta inscrição cuneiforme, a carruagem cerimonial de Senaquerib, cavaleiros desmontados, o carro de batalha do rei e, finalmente, o acampamento fortificado assírio.

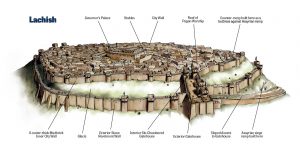

Laquis nos oferece uma oportunidade única de comparar um relevo assírio esculpido em pedra, que descreve detalhadamente uma cidade antiga, com o local da mesma cidade cuja topografia e fortificações são bem conhecidas por nós. Embora muitas cidades inimigas sejam mostradas nos relevos encontrados em vários palácios reais da Assíria, apenas um punhado delas pode ser identificado pelo nome. No caso de Laquis, no entanto, não apenas conhecemos bem o cenário topográfico, como também identificamos o estrato arqueológico da cidade que foi destruída pelos assírios e descobrimos os restos do ataque a essa cidade.

Nos relevos, as várias características da cidade são retratadas de acordo com as convenções rígidas e esquemáticas usuais dos artistas assírios, mas são mostradas em uma certa perspectiva, mantendo aproximadamente as proporções e relações dos vários elementos, como pareceriam para um artista observando os acontecimentos a partir de um ponto específico. Na opinião de David Ussishkin o ponto de vista a partir do qual Laquis é mostrado nos relevos está localizado a sudoeste do monte, em frente ao local presumido do acampamento assírio, entre ele e a cidade, e de frente para o principal ponto de ataque. Creio que este é o local exato em que Senaquerib, o comandante supremo, sentou-se em seu belo trono, conduziu a batalha e depois inspecionou os carregadores do saque e os deportados. Consequentemente, acredito que os relevos de Laquis apresentam a cidade sitiada como pode ser vista através dos olhos do próprio Senaquerib no seu posto de comando.

The Lachish Reliefs

A few years after the campaign in the Levant and the subjugation of Judah, Sennacherib constructed his royal palace in Nineveh, known today as the Southwest Palace. This extravagant edifice, its construction, size, magnificence and beauty are recorded in detail in Sennacherib’s inscriptions; he proudly called it the “Palace Without Rival.” The palace was largely excavated in 1850 c.e. by Sir Austen Henry Layard on behalf of the British Museum in London. He prepared a plan of the building and uncovered a large number of reliefs cut on alabaster slabs which adorned the walls.

The stone slabs depicting in relief the conquest of Lachish were erected in a special room located at the back of a central ceremonial suite in the palace. It seems that the whole room—and perhaps also the entire suite— was intended to commemorate the conquest of Judah and the victory at Lachish. According to our reconstruction, the “Lachish room” (labeled by Layard “Room XXXVI”) was 11.5m (35ft) wide and 5m (15ft) long. Its walls were probably entirely covered by the Lachish reliefs. The stone reliefs on the left side of the room were left by Layard on the site and were thus lost, while the rest of the series, comprising twelve slabs, were transferred by him to the British Museum in London and are currently exhibited there. The length of the preserved series is about 19m (57ft). It seems that the missing part of the series was about 8m (24ft) long. Accordingly, the original series depicting the conquest of Lachish must have been about 27m (81ft) long. This is the longest and most detailed series of Assyrian reliefs depicting the storming and conquest of a single fortress city.

The stone slabs depicting in relief the conquest of Lachish were erected in a special room located at the back of a central ceremonial suite in the palace. It seems that the whole room—and perhaps also the entire suite— was intended to commemorate the conquest of Judah and the victory at Lachish. According to our reconstruction, the “Lachish room” (labeled by Layard “Room XXXVI”) was 11.5m (35ft) wide and 5m (15ft) long. Its walls were probably entirely covered by the Lachish reliefs. The stone reliefs on the left side of the room were left by Layard on the site and were thus lost, while the rest of the series, comprising twelve slabs, were transferred by him to the British Museum in London and are currently exhibited there. The length of the preserved series is about 19m (57ft). It seems that the missing part of the series was about 8m (24ft) long. Accordingly, the original series depicting the conquest of Lachish must have been about 27m (81ft) long. This is the longest and most detailed series of Assyrian reliefs depicting the storming and conquest of a single fortress city.

The missing relief slabs were not documented, and the only hint as to their content is Layard’s remark that “the reserve consisted of large bodies of horsemen and charioteers.” Further along, in consecutive order from left to right, are shown the attacking infantry, the storming of the city, the transfer of booty, punishment of captives, families going into exile, Sennacherib sitting on his throne, the royal tent and chariot, and finally the Assyrian military camp. Significantly, the main scene portraying the storming of the city was placed exactly in the center of the rear wall of the room, opposite the monumental entrance. Given good lighting conditions, anyone who passed through the entrance could see the storming of Lachish facing him as he entered the room.

The city-gate is shown in the center of the scene portraying the assault on the city, being attacked by a siege-machine. Refugees are shown carrying their belongings and leaving the city through the gate. On both sides of the besieged city are depicted the city-walls. Judahite warriors stand on the walls and on the “balcony” on the roof of the gatehouse and shoot at the attacking Assyrians. The siege-ramp is shown to the right of the gatehouse. As mentioned above, seven siege-machines, supported by archers and slingers, are attacking the walls—five on top of the siegeramp, and two attacking the city-gate, possibly placed on an additional siege-ramp built against the gatehouse. The royal Assyrian relief series usually portray one, and in a few cases two siege-machines attacking the walls of a besieged city. The relief portraying the siege of Lachish is unique in showing no fewer than seven siege-machines taking active part in the battle.

Further to the right are shown Assyrian soldiers carrying booty and captives—probably Hezekiah’s officials, being severely punished—and the inhabitants of Lachish  leaving the destroyed city. The deported Lachishites take their belongings with them, a tragic picture of entire families forced out of their homes. The family shown here consists of two women, followed by two girls and a man leading a cart harnessed totwo oxen. The cart is laden with household goods and tied-up bundles on which two small children, a boy and a girl, are sitting. The ribs of the oxen are emphasized, possibly to point out that they suffer from malnutrition.

leaving the destroyed city. The deported Lachishites take their belongings with them, a tragic picture of entire families forced out of their homes. The family shown here consists of two women, followed by two girls and a man leading a cart harnessed totwo oxen. The cart is laden with household goods and tied-up bundles on which two small children, a boy and a girl, are sitting. The ribs of the oxen are emphasized, possibly to point out that they suffer from malnutrition.

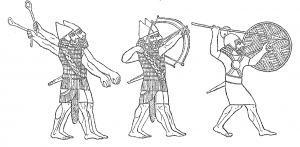

The deportees are distinguishable by their appearance and dress, which were probably typical to the people of Judah at that period. The women wear a long, simple garment. A long shawl covers their head, shoulders and back, reaching to the bottom of the dress. The men have a short beard and their heads are wound with scarves whose fringed ends hang down. Their garment has a fringed tassel hanging between the legs. Both men and women are barefoot.

The procession of the Assyrian soldiers carrying booty, and that of the deported inhabitants, face the Assyrian king sitting on his throne. The cuneiform inscription, carved in the background of the relief, identifies the assaulted city as Lachish. The beautiful throne is richly ornamented and is specifically mentioned in the inscription; it was almost certainly brought from Assyria to Lachish for the use of Sennacherib. The throne has very high legs, enabling the sitting monarch to look down from above at the people standing in front of him. The feet of the king rest on a high footstool. Both the throne and the stool were decorated with beautifully carved ivories. Facing the king stands a high official, possibly the commander of the army (Tartan/turtanu). He is followed by commanders of lesser rank, and two eunuchs holding fans stand behind the throne. Further to the right are shown the royal tent, identified as Sennacherib’s tent by a short cuneiform inscription, the ceremonial chariot of Sennacherib, dismounted cavalrymen, the king’s battle chariot and finally the Assyrian fortified camp, depicted in the schematic Assyrian style as described above.

Lachish provides us with a unique opportunity of comparing an Assyrian stone relief depicting in detail an ancient city with the site of the same city whose topography and fortifications are well known to us. Although many enemy cities are shown in the reliefs found in various Assyrian royal palaces, only a handful of them can be identified by name, and even fewer can be associated with places of known location and nature. In the case of Lachish, however, not only are we well acquainted with the topographical setting, but we have identified the city level that was destroyed by the Assyrians and uncovered the remains of the attack on that city.

It seems to me, in following the initial study of Richard Barnett, that the Lachish relief series portrays the city from one particular spot. In the relief, the various features of the city are depicted according to the usual rigid and schematic conventions of the Assyrian artists, but they are shown in a certain perspective, roughly maintaining the proportions and relationships of the various elements as they would appear to an onlooker standing at one specific point. In my view the particular vantage point from which Lachish is shown in the relief is located southwest of the mound, just in front of the presumed site of the Assyrian camp, between it and the city, and facing the main point of attack. I believe that this is the very spot where Sennacherib, the supreme commander, sat on his beautiful throne, conducted the battle, and later reviewed the booty bearers and the deportees. Consequently, I believe that the Lachish reliefs present the besieged city as seen through the eyes of Sennacherib himself at his command post.