Em 1177 a.C., grupos de invasores, que hoje chamamos de “povos do mar”, chegaram ao Egito. As forças militares egípcias, sob o comando do faraó Ramsés III, conseguiram derrotá-los, mas a vitória enfraqueceu tanto o Egito, que logo o então poderoso reino caiu em declínio, assim como a maioria das civilizações vizinhas.

Depois de séculos de existência de brilhantes civilizações, o mundo da Idade do Bronze chegou a um fim abrupto e cataclísmico. De acordo com as inscrições de Ramsés III, nenhum país foi capaz de se opor à pressão dos “povos do mar”.

III, nenhum país foi capaz de se opor à pressão dos “povos do mar”.

As grandes potências da época realmente caíram uma a uma: Hatti e Ugarit desapareceram, Babilônia e Assíria encolheram, o Egito saiu enfraquecido.

A prosperidade econômica e cultural do final do segundo milênio a.C., que se estendia da Grécia ao Egito e à Mesopotâmia, deixou repentinamente de existir, juntamente com sistemas de escrita, tecnologia e arquitetura monumental.

Mas os “povos do mar” sozinhos não poderiam ter causado um colapso tão generalizado. Como isso aconteceu?

Em 1177 a.C.: o ano em que a civilização entrou em colapso, Eric H. Cline nos conta a emocionante história de como o colapso foi causado por múltiplos fatores interligados, desde invasão e revolta até terremotos, seca e bloqueio das rotas do comércio internacional.

Agora, dando continuidade à narrativa, Eric H. Cline nos oferece Depois de 1177 a.C.: a sobrevivência das civilizações.

Transcrevo, a seguir, um trecho do livro Depois de 1177 a.C., onde se fala de Tiglat-Pileser I (1115-1076 a.C.), rei da Assíria.

Está no capítulo 2 e o título é: Conquistador de todas as terras, vingador da Assíria. Pois é assim que, em uma inscrição, se apresenta Aššur-reša-iši I, rei da Assíria de 1133 a 1116 a.C. Ele é o pai de Tiglat-Pileser I. Agora, Eric H. Cline.

De modo geral, os assírios e babilônios provaram estar entre as sociedades afetadas mais resilientes e bem sucedidas em sua resistência às consequências do colapso. Eles foram capazes de reter o conhecimento da escrita, realizar grandes projetos de construção e manter seus sistemas de governo em funcionamento.

No entanto, mesmo eles não escaparam ilesos. Por exemplo, evidências arqueológicas obtidas a partir de pesquisas na região da antiga Babilônia sugerem que pode ter havido uma diminuição na população de até 75 por cento durante os trezentos anos entre o colapso no final da Idade do Bronze e o início do ressurgimento da Babilônia. depois de 900 a.C.

Além disso, de acordo com A. Kirk Grayson, um renomado estudioso da Universidade de Toronto que foi responsável pela publicação de todas as inscrições reais assírias conhecidas, em uma série de volumes que apareceram a partir do final dos anos 80 do século XX, quase não há inscrições reais que datam do período de setenta e cinco anos desde o final do reinado de Tukulti-Ninurta I em 1208 a.C até a época de Aššur-reša-iši I (1133-1116 a.C.) É especialmente surpreendente que não existam tais inscrições reais deixadas para nós por um rei chamado Aššur-dan I, que governou por quase cinquenta anos durante este período, de 1179 a 1133 a.C.

Além disso, de acordo com A. Kirk Grayson, um renomado estudioso da Universidade de Toronto que foi responsável pela publicação de todas as inscrições reais assírias conhecidas, em uma série de volumes que apareceram a partir do final dos anos 80 do século XX, quase não há inscrições reais que datam do período de setenta e cinco anos desde o final do reinado de Tukulti-Ninurta I em 1208 a.C até a época de Aššur-reša-iši I (1133-1116 a.C.) É especialmente surpreendente que não existam tais inscrições reais deixadas para nós por um rei chamado Aššur-dan I, que governou por quase cinquenta anos durante este período, de 1179 a 1133 a.C.

Talvez devêssemos ver esta falta de registros reais durante este período como um sinal de que os assírios foram mais afetados pelo colapso no final da Idade do Bronze do que pensávamos. No entanto, não podemos ter certeza disso, especialmente porque eles poderiam ter escrito em materiais perecíveis, como couro, madeira ou tiras de chumbo, mesmo que, por algum motivo, tivessem parado temporariamente de registrar inscrições reais em pedra. Por outro lado, Eckart Frahm, um assiriologista da Universidade de Yale, salienta que as inscrições reais normalmente teriam sido escritas em pedra ou argila, pelo que a lacuna pode, de fato, ser significativa.

Felizmente, como mencionado, os registros reais assírios começam novamente com o reinado de Aššur-reša-iši I, numa época em que pode ter havido uma trégua de cinquenta anos na seca que vinha afetando todo o Mediterrâneo Oriental e as regiões do Egeu (…) Se assim for, Aššur-reša-iši teria se beneficiado deste alívio climático temporário.

Tiglat-Pileser I

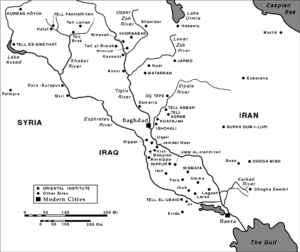

Aššur-reša-iši foi sucedido por seu filho, Tiglat-Pileser I, que subiu ao trono assírio em 1115 a.C. Seu reinado durou quase quarenta anos, até 1076 a.C. Como seu pai, ele se vangloriou, afirmando a certa altura que havia cruzado o Eufrates em um total de vinte e oito vezes, duas vezes por ano durante quatorze anos, em perseguição aos arameus. Ele também, como seu pai, resistiu a um ou dois ataques dos babilônios, inclusive mais uma vez de Nabucodonosor I.

Ele é conhecido por nós em parte por causa das muitas inscrições deixadas por seus escribas que descrevem suas proezas, muitas das quais são provavelmente uma hipérbole:

“Tiglat-Pileser, rei forte, rei do universo, rei da Assíria, rei de todos os quatro quadrantes, sitiador de todos os criminosos, jovem valente, homem poderoso e impiedoso que age com o apoio dos deuses Assur e Ninurta, os grandes deuses, seus senhores, e (assim) derrubou seus inimigos, príncipe atento que, pelo comando do deus Shamash, o guerreiro, conquistou, por meio de força e poder, a Babilônia desde a terra de Akkad até o Mar Superior da terra de Amurru e o mar das terras Nairi e tornou-se senhor de tudo. . . soldado de assalto cujas batalhas ferozes todos os príncipes dos quatro quadrantes temiam, de modo que eles se esconderam como morcegos e fugiram para regiões inacessíveis como o jerboa” [um pequeno roedor saltitante do deserto].

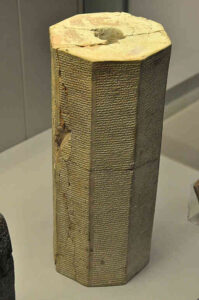

Os escribas também registraram, em numerosos prismas octogonais de argila e com grandes e muitas vezes horríveis detalhes, o que Tiglat-Pileser I fez aos infelizes soldados inimigos que não se esconderam ou fugiram para regiões inacessíveis depois de tê-los derrotado em batalha. Por exemplo, depois de ter supostamente derrotado uma coalizão de cinco reis e seu exército combinado de vinte mil homens em uma batalha travada durante o primeiro ano de seu reinado, ele profanou os cadáveres, saqueou suas propriedades e fez o resto prisioneiro:

“Como um demônio da tempestade, empilhei os cadáveres de seus guerreiros no campo de batalha e fiz seu sangue fluir para as cavidades e planícies das montanhas. Cortei-lhes as cabeças e empilhei-as como se fossem montes de cereais em volta das suas cidades. Eu trouxe seus despojos, propriedades e posses incontáveis. Peguei os 6 mil soldados restantes que fugiram de minhas armas e se submeteram a mim e os considerei como pessoas da minha terra”.

A inscrição continua então numa linha semelhante, descrevendo vitórias sobre numerosos outros grupos, listando cada um pelo nome, abrangendo partes do que hoje é a Turquia, o Iraque e as áreas costeiras do Levante.

Turquia, o Iraque e as áreas costeiras do Levante.

Além disso, as maldições que Tiglat-Pileser I disse aos escribas para adicionarem no final desta longa inscrição foram suficientes para fazer qualquer um hesitar. Ele as dirigiu a quem

“quebra ou apaga minhas inscrições monumentais ou de argila, as joga na água, queima-as, cobre-as com terra. . . quem apaga meu nome inscrito e escreve seu próprio nome, ou quem concebe algo prejudicial e o põe em prática em detrimento de minhas inscrições monumentais”.

Invocando os deuses Anu e Adad para amaldiçoar o potencial ofensor, que presumia ser um futuro rei ou governante, ele então escreveu:

“Que eles derrubem sua soberania. Que eles destruam os fundamentos do seu trono real. Que eles acabem com sua linhagem nobre. Que eles destruam suas armas, provoquem a derrota de seu exército e o façam sentar-se acorrentado diante de seus inimigos. Que o deus Adad atinja sua terra com relâmpagos terríveis e inflija angústia, fome, necessidade e peste em sua terra. Que ele ordene que não viva mais um dia. Que ele destrua seu nome e sua descendência da terra”.

E, sobre os arameus em particular, uma inscrição antiga observa que Tiglat-Pileser I conquistou seis de suas cidades, incendiando-as e saqueando seus bens. Ele também massacrou muitas de suas tropas, perseguindo-as através do Eufrates em jangadas feitas de peles de cabra infladas.

Embora estivessem entre os oponentes mais perigosos dos assírios nessa época e fossem frequentemente considerados arqui-inimigos do rei assírio, especialmente durante os primeiros anos de Tiglat-Pileser I, os arameus não eram seus únicos oponentes. Tiglat-Pileser afirma na mesma inscrição inicial ter obtido controle sobre uma variedade de outras terras, montanhas, cidades e príncipes que também eram hostis a ele e a Assur.

“Eu lutei contra 60 cabeças coroadas e consegui a vitória sobre eles em batalhas, acrescentando território à Assíria e pessoas à sua população”, vangloriou-se. “Eu estendi a fronteira da minha terra e governei todas as suas terras”.

Em outras inscrições, incluindo uma série de tabuinhas, bem como fragmentos de obeliscos encontrados por arqueólogos em Assur, além do chamado Obelisco Quebrado que foi encontrado em Nínive, Tiglat-Pileser descreve a reconstrução e a restauração de vários palácios e outros edifícios em Assur e outros lugares, bem como a escavação de canais há muito negligenciados. Ele também documentou ainda mais campanhas, inclusive no que hoje é a Síria e o Líbano, a oeste. Ele matou e/ou capturou touros selvagens, elefantes e leões no sopé do Monte Líbano e em outros lugares, bem como panteras, tigres, ursos, javalis e avestruzes, cortou e carregou vigas de cedro para usar em um templo em casa , e então continuou para a terra de Amurru (litoral do norte da Síria) e a conquistou.

Ele também recebeu homenagens das cidades costeiras de Biblos, Sídon e Arwad, onde os fenícios estavam começando a se estabelecer, e lista presentes de animais exóticos (…) Esta é a primeira vez que estas cidades costeiras fenícias são mencionadas numa inscrição estrangeira desde o colapso da Idade do Bronze (…).

Vale notar que o novo mundo do final do século XII a.C. era muito diferente do ápice da Idade do Bronze Recente no século XIV a.C. Naquela época, os reis da Assíria faziam parte das Grandes Potências e trocavam enormes presentes reais com outros reis, do Egito a Hattusa, enquanto os reis menores de Biblos, Sídon, Tiro e outras cidades cananeias próximas praticavam comércio e diplomacia entre si e com as grandes potências.

Agora, com Tiglat-Pileser I no comando, e especialmente mais tarde, a partir do século IX, como ficará evidente, os assírios simplesmente tiravam o que queriam dos fenícios e de outros, seja saqueando as cidades menores derrotadas, e apreendendo o que precisavam, ou cobrando tributo, ou ambos.

Overall, the Assyrians and the Babylonians proved to be among the most resilient and successful of the affected societies to weather the aftermath of the Collapse. They were able to retain their knowledge of writing, undertake massive building projects, and keep their systems of government in place. However, even they did not escape unscathed. For instance, archaeological evidence obtained from surveys in the region of ancient Babylonia suggests that there may have been a decrease in population of up to 75 percent during the three hundred years between the Collapse at the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of Babylonian resurgence after 900 BC

In addition, according to A. Kirk Grayson, a renowned scholar at the University of Toronto who was responsible for publishing all the known royal Assyrian inscriptions in a series of volumes that appeared from the late 1980s onward, there are almost no royal inscriptions that date to the seventy-five-year period from the end of the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I in 1208 BC u ntil the time of Aššur-reša-iši I. It is especially surprising that there are no such royal inscriptions left to us by a king named Aššur-dan I, who ruled for almost fifty years during this period, from 1179 to 1133 BC.

In addition, according to A. Kirk Grayson, a renowned scholar at the University of Toronto who was responsible for publishing all the known royal Assyrian inscriptions in a series of volumes that appeared from the late 1980s onward, there are almost no royal inscriptions that date to the seventy-five-year period from the end of the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I in 1208 BC u ntil the time of Aššur-reša-iši I. It is especially surprising that there are no such royal inscriptions left to us by a king named Aššur-dan I, who ruled for almost fifty years during this period, from 1179 to 1133 BC.

It may be that we should see this lack of royal records during this period as a sign that the Assyrians were more affected by the Collapse at the end of the Bronze Age than we thought. However, we cannot know this for certain, especially since they could conceivably have been writing on perishable materials such as leather, wood, or lead strips, even if they had for some reason temporarily ceased to record royal inscriptions on stone. On the other hand, Eckart Frahm, an Assyriologist at Yale University, points out that royal inscriptions would usually have been written on stone or clay, so the gap may indeed be meaningful.

Fortunately, as mentioned, the royal Assyrian records begin again with the reign of Aššur-reša-iši I, at a time when there may have been a fifty-year respite to the drought that had been impacting the entire Eastern Mediterranean and Aegean regions; I will discuss this further below.20 If so, Aššur-reša-iši I will have benefited from this temporary climactic reprieve.

Tiglath-Pileser I

Aššur-reša-iši was eventually succeeded by his son, Tiglath-Pileser I, who came to the Assyrian throne in 1115 BC. His reign lasted nearly forty years, until 1076 BC. He made boasts similar to those of his father, stating at one point that he had crossed the Euphrates a total of twenty-eight times, twice a year for fourteen years, in pursuit of the Aramaeans. He also, like his father, withstood an attack or two by the Babylonians, including yet again by Nebuchadnezzar I.

He is known to us in part because of the many inscriptions left behind by his scribes that describe his prowess, much of which is probably hyperbole:

“Tiglath-pileser, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of all the four quarters, encircler of all criminals, valiant young man, merciless mighty man who acts with the support of the gods Aššur and Ninurta, the great gods, his lords, and (thereby) has felled his foes, ttentive prince who, by the command of the god Shamash the warrior, has conquered by means of conflict and might from Babylon from the land Akkad to the Upper Sea of the land Amurru and the sea of the lands Nairi and become lord of all. . . storm-trooper whose fierce battles all princes of the four quarters dreaded so that they took to hiding places like bats and scurried off to inaccessible regions like jerboa” [a small, hopping desert rodent].

The scribes also recorded, on numerous clay octagonal prisms and in great and often gruesome detail, what Tiglath-Pileser I did to the unfortunate enemy soldiers who did not take to hiding places or scurry off to inaccessible regions after he defeated them in battle. For example, after having reportedly overwhelmed a coalition of five kings and their combined army of twenty thousand men in a battle fought during the first year of his reign, he proceeded to desecrate the corpses, loot their property, and take the rest prisoner:

“Like a storm demon I piled up the corpses of their warriors on the battlefield and made their blood flow into the hollows and plains of the mountains. I cut off their heads and stacked them like grain piles around their cities. brought out their booty, property, and possessions without number. I took the remaining 6,000 of their troops who had fled from my weapons and submitted to me and regarded them as people of my land”.

The inscription then continues in a similar vein, describing victories over numerous other groups, listing each by name, ranging far and wide over parts of what is now Turkey, Iraq, and coastal areas of the Levant.

In addition, the curses that Tiglath-Pileser I told the scribes to add at the end of this long inscription were enough to give anyone pause. He addressed these to whomever

“breaks or erases my monumental or clay inscriptions, throws them into water, burns them, covers them with earth . . . who erases my inscribed name and writes his own name, or who conceives of anything injurious and puts it into effect to the disadvantage of my monumental inscriptions.”

Invoking the gods Anu and Adad to curse the potential offender, whom he assumed would be a future king or ruler, he then wrote:

“May they overthrow his sovereignty. May they tear out the foundations of his royal throne. May they terminate his noble line. May they smash his weapons, bring about the defeat of his army, and make him sit in bonds before his enemies. May the god Adad strike his land with terrible lightning and inflict his land with distress, famine, want, and plague. May he command that he not live one day longer. May he destroy his name and his seed from the land.”

the defeat of his army, and make him sit in bonds before his enemies. May the god Adad strike his land with terrible lightning and inflict his land with distress, famine, want, and plague. May he command that he not live one day longer. May he destroy his name and his seed from the land.”

And, about the Aramaeans in particular, an early inscription notes that Tiglath-Pileser I conquered six of their cities, burning them to the ground and looting their possessions. He also massacred many of their troops, pursuing them across the Euphrates on rafts made from inflated goatskins.

Although they w ere among the Assyrians’ most dangerous opponents at this time and were frequently cast as the archenemy of the Assyrian king, especially during the early years of Tiglath-Pileser I, the Aramaeans were not his only opponents. Tiglath-Pileser claims in the same early inscription to have gained control over a variety of other lands, mountains, towns, and princes who were also hostile to him and to Aššur.

“I vied with 60 crowned heads and achieved victory over them in battles, add[ing] territory to Assyria and people to its population,” he boasted. “I extended the border of my land and ruled over all their lands.”

In other inscriptions, including a series of clay tablets as well as fragments of obelisks found by archaeologists at the site of Aššur, plus the so-called Broken Obelisk that was found at Nineveh and has now been redated to his reign, Tiglath-Pileser describes rebuilding and restoring various palaces and other buildings in Aššur and elsewhere, as well as digging out long-neglected moats and canals. He also documented yet more campaigns, including in what is now Syria and Lebanon to the west. He killed and/or captured wild bulls, elephants, and lions at the foot of Mount Lebanon and elsewhere, as well as panthers, tigers, bears, boars, and ostriches, cut down and carried off cedar beams to use in a temple back home, and then continued on to the land of Amurru (coastal North Syria) and conquered it.

He also received tribute from the coastal cities of Byblos, Sidon, and Arwad, where the Phoenicians were beginning to establish themselves, and lists gifts of exotic animals, which included a crocodile and a “large female monkey of the seacoast.” He clarifies on the Broken Obelisk and elsewhere that these latter animals were given to him by an Egyptian pharaoh (probably Ramses XI, the last king of the Twentieth Dynasty), and that they also included a “river-man,” which was previously identified as a water buffalo or perhaps a hippopotamus but has now been recently reidentified as more likely to be a Mediterranean monk seal.

Tiglath-Pileser also says that he took a six-hour boat ride while at Arwad and that, while at sea, he killed “a nahiru, which is called a sea-horse.” In a later inscription, he says specifically that he killed it with a harpoon of his own making. Although there has been a fair amount of discussion, scholars have still not decided what exactly is a nahiru; some have suggested that it was some kind of small whale, seal, or shark, but another text mentions ivory from a nahiru, so that would indicate teeth or a tusk of some sort and, in fact, current opinion may be leaning toward an identification as a hippopotamus.

Tiglath-Pileser also says that he took a six-hour boat ride while at Arwad and that, while at sea, he killed “a nahiru, which is called a sea-horse.” In a later inscription, he says specifically that he killed it with a harpoon of his own making. Although there has been a fair amount of discussion, scholars have still not decided what exactly is a nahiru; some have suggested that it was some kind of small whale, seal, or shark, but another text mentions ivory from a nahiru, so that would indicate teeth or a tusk of some sort and, in fact, current opinion may be leaning toward an identification as a hippopotamus.

This is the first time that these Phoenician coastal cities have been mentioned in an inscription not of their own making since the Collapse of the Bronze Age. I will discuss them at greater length in the next chapter, but for now we can put them into context, for the new world of the late twelfth century BC was very different from the high point of the Late Bronze Age in the fourteenth century BC. Back then, the kings of Assyria were part of the Great Powers and exchanged huge royal gifts with other kings, from Egypt to Hattusa, while the smaller, petty kings of Byblos, Sidon, Tyre, and other nearby Canaanite cities practiced trade and diplomacy with both each other and the Great Powers. Now, with Tiglath-Pileser I at the helm, and especially later, from the ninth century onward, as will become apparent, the Assyrians simply took what they wanted from the Phoenicians and others, either by looting the smaller, defeated cities and seizing what they needed or by exacting tribute, or both.

Fonte: CLINE, E. H. After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2024, p. 47-52.

As notas de rodapé deste trecho, números 17 a 29, foram aqui omitidas.

Sobre o livro: Depois de 1177 a.C.: a sobrevivência das civilizações. Post publicado no Observatório Bíblico em 13.11.2023

Para os textos assírios: GRAYSON, A. K. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC: I (1114–859 BC). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991 (disponível para download em pdf em Internet Archive)

Uma observação sobre as fontes assírias: Elas precisam ser encaradas com cautela [cum grano salis], pois estão cheias de hipérboles e os números podem muito bem ser exagerados. Apesar de uma fonte, às vezes, divergir de outra, uma coisa é sempre constante e consistente: aparentemente os reis assírios nunca foram derrotados, o que parece um pouco difícil de acreditar. Claramente, os textos eram tanto propaganda quanto registros de eventos históricos.