Encontrei este texto na internet e o achei muito bem feito. Abaixo a reprodução em espanhol.

Sobre el nacimiento y nombre de Jesús de Nazaret

¿Nombre?

Yeshua bar Yosef.

¿Fecha y lugar de nacimiento?

….

¿Que habría respondido Jesús, ya de adulto, si un soldado romano, quizás para cumplimentar un censo, le hubiera hecho estas preguntas? Para la tradición cristiana, las respuestas son obvias. Jesús nació en Belén el 25 de diciembre del año 1 a. C., apenas seis días antes de que comenzara el año 1 de nuestra era.

Vayamos por partes. Para el mundo actual, se trata de Jesús de Nazaret o Jesucristo. Sin embargo, todas estas denominaciones son fruto de la tradición cristiana. Jesús es la versión griega del nombre original hebreo, Yeshua. Jesucristo supone la fusión de dos conceptos, el nombre propio y el de la palabra griega jristós, “ungido”, traducción a su vez del hebreo meshiah, que designaba al heredero al trono de Israel, que era ungido con aceite sobre su cabeza como forma de coronación. Por su parte, Jesús de Nazaret indica el lugar de residencia o nacimiento (ya lo veremos), quizás incluso una especie de apodo si, en lugar de Nazaret, se entiende como Nazareno, Nazireo, Nazir, aquel que se consagraba a Dios mediante un voto personal y se comprometía a no cortarse el cabello, y a no consumir licor ni alimentos impuros, tal como se describe en Jueces 13, 4-7 a propósito de Sansón. Sin embargo, ninguna de estas formas refleja el modo habitual de nombrar a alguien en la Judea del siglo primero. Lo normal es que fuese conocido como Yeshua bar Yosef (Jesús, hijo de José) en su forma aramea (bar en lugar del hebreo ben), pues el arameo era la lengua que se hablaba en aquel tiempo, mientras que el hebreo había quedado como lengua litúrgica, de un modo similar al latín en el mundo católico actual.

¿Cuán nació Yeshua bar Yosef? Contamos como fuentes de información con los relatos de los dos Evangelios de la Infancia, el de Mateo (capítulos 1 y 2) y el de Lucas (Capítulos 1 al 3), y en ellos se nos ofrecen dos anclajes cronológicos: el primero, en Lucas 1, 5 y Mateo 2, 1, que Jesús nació en tiempos del rey Herodes el Grande (40-4 a. C.), y el segundo, en Lucas 2, 1-2, que coincidió con el censo que, en tiempos de Augusto, Quirino llevó a cabo en la provincia romana de Siria, y del que también tenemos noticias por Flavio Josefo, quien tanto en sus Antigüedades de los judíos XVII, 355 y XVIII 1.2.26.102, como en su Guerra Judía VII, 253, se refiere a él y destaca su carácter novedoso y sin precedentes. El problema es que Quirino solo fue gobernador de la provincia de Siria (que en ese momento ya incluía Judea) en el año 6 de nuestra era. Así pues, las dos noticias son irreconciliables desde un punto de vista cronológico.

Sin embargo, la mención de este censo puede explicarse como un recurso de Lucas para explicar por qué José y María hubieron de marchar desde su lugar de residencia en Galilea hasta Belén, todo ello para hacer que se cumpla la profecía del nacimiento del Mesías en la ciudad natal del rey David (véase más abajo). Además, esta fecha se contradice igualmente con otro dato que nos ofrece el mismo evangelista, a saber, que Jesús tenía unos treinta años cuando comenzó su predicación (Lucas 3, 23). Asumiendo que su predicación duró unos tres años, y que fue crucificado siendo gobernador de Judea Poncio Pilato (26-36 d.C.), deberemos situar su nacimiento entre los años 7 a.C. y 3 d.C., lo que, en las fechas más bajas nos sitúa en el reinado de Herodes pero en ningún caso lo ponen en relación con el censo de Quirino.

Pese al relato del milagroso nacimiento en Belén que podemos leer en Mateo y Lucas, lo más probable es que se trate de una elaboración literaria para identificar a Jesús con el Mesías anunciado en el Antiguo Testamento. De hecho, así lo indica el evangelista Mateo, que no pierde la ocasión de señalar que, con el nacimiento de Jesús en Belén, se cumplen las palabras del profeta Miqueas 5, 1:

“Pero tú, Belén de Efratah, aunque pequeña para figurar en los clanes de Judá, de ti me saldrá quien ha de ser dominador de Israel, cuyo origen viene de antaño, desde los días antiguos”.

Más allá de estos versículos, a nadie se le escapaba que Belén había sido la cuna del rey David y que, por lo tanto, resultaría lógico que también naciese en esa ciudad el Mesías, descendiente de David y en el que se encarnaba la promesa hecha al rey en 2Samuel 7, 12-16: “cuando tu vida llegue a su fin y vayas a descansar entre tus antepasados, yo pondré en el trono a uno de tus propios descendientes, y afirmaré su reino. Será él quien construya una casa en mi honor, y yo afirmaré su trono real para siempre. Yo seré su padre, y él será mi hijo. Así que, cuando haga lo malo, lo castigaré con varas y azotes, como lo haría un padre. Sin embargo, no le negaré mi amor, como se lo negué a Saúl, a quien abandoné para abrirte paso. Tu casa y tu reino durarán para siempre delante de mí; tu trono quedará establecido para siempre”.

Pero no sólo el lugar de nacimiento es fruto de la necesidad de situar a Jesús dentro del esquema del esperado Mesías, sino que hay otros elementos de la historia que cumplen esta misma función. Cuando los magos de Oriente se presentan ante Herodes para preguntarle por el recién nacido, el rey, asustado ante la posibilidad de perder su trono, ordena el asesinato de todos los niños menores de dos años de Belén. Resulta sorprendente que Flavio Josefo, enemigo acérrimo de Herodes el Grande, no consigne este hecho en su Guerra de los Judíos, cuando puso el mayor empeño en citar, uno por uno, todos los crímenes imputables al monarca idumeo. ¿Cómo se explica pasar por alto semejante masacre, la prueba concluyente de la abyección de Herodes? Sencillamente, porque nunca sucedió. Hay que hacer notar la similitud entre este episodio y otro del Antiguo Testamento, en Éxodo 1, sobre el nacimiento de Moisés, donde el faraón ordena la muerte de todos los niños hebreos de su reino. El propósito de esta narración es doble. Por una parte, al atribuir el crimen a Herodes, se proporciona un marco histórico adecuado y creíble a la profecía de Jeremías 31, 15:

Jeremías 31, 15:

Una voz se oyó en Ramá,

Un llanto y un gran lamento:

Raquel llorando a sus hijos

¡Y no quería consolarse, porque ya no existen!

Este versículo, trasladado al Nuevo Testamento, identifica a Raquel con el pueblo de Belén, donde se encuentra su tumba. Y así, los hijos de Raquel son los niños asesinados en Belén por orden de Herodes.

Por otro lado, dentro de este relato, Jesús sufre una persecución que es típica de aquellos niños llamados a cumplir una misión fuera del alcance del común de los humanos. Es un peligro que no sólo amenaza a Moisés, sino también a Rómulo y Remo o Ciro, entre otros. De este modo, el lector del Nuevo Testamento, fuese judío o gentil, vería claro desde el principio que el protagonista del relato que estaba leyendo era un personaje fuera de lo común, alguien que encajaba en el prototipo de héroe nacional o mitológico. Pero la identificación va más allá. A ningún lector del siglo primero se le pasaría por alto la similitud ya mencionada entre la matanza de los inocentes y la del faraón en tiempos de Moisés. Hay que recordar que Moisés es el encargado de recibir la Ley de Dios en el monte Sinaí, y que Jesús es el encargado de darla por superada en su Sermón de la Montaña. Así pues, el relato de Mateo presentaba a Jesús como el nuevo Moisés, llamado a superar al primero.

Fuera de estas menciones en los llamados Evangelios de la Infancia de Mateo y Lucas, todos los indicios del resto de textos evangélicos apuntan en otra dirección diferente a Belén: Jesús nació probablemente en Galilea, unos trescientos kilómetros al norte de Jerusalén y de la propia ciudad natal de David. En numerosas ocasiones recibe el nombre de Iesous ho nazarenos o ho Nazoraios, lo que, para algunos, significa que era natural de Nazaret, en Galilea, que se suele citar como patria de Jesús y su familia (“y llegó a Nazaret, donde se había criado”, Lc 4, 16, aunque nótese que no dice que naciese allí).

En la época que nos ocupa, Nazaret era un lugar tan ínfimo que a duras penas obtendría la consideración de pueblo. Las excavaciones arqueológicas han revelado poco más que algunas grutas donde vivirían en condiciones muy precarias una pocas familias. Al contemplarlas, no podemos sino recordar la incredulidad de Natanel cuando le cuentan que han encontrado a aquél del que había escrito Moisés en la ley y los profetas: “Jesús, hijo de José, el de Nazaret”, y Natanel pregunta sorprendido: “¿De Nazaret puede haber algo bueno?” (Juan 1, 46).

Sin embargo, aunque no exista ninguna prueba que lo confirme, creo que no debería descartarse la posibilidad de que Jesús naciese en Cafarnaún, un pueblo de cierta importancia situado en la orilla norte del Mar de Galilea, y en cuyos alrededores se desarrolla la acción de la mayoría de los episodios del comienzo de la predicación de Jesús. Por ejemplo, Jesús enseña en la sinagoga de Cafarnaún, y cerca de allí tiene lugar el milagro de la multiplicación de los panes y los peces, la curación de la suegra de Pedro, la vocación de los discípulos, la tempestad calmada, etc. De hecho, sus primeros discípulos son todos originarios de Cafarnaún o de la vecina Betsaida.

Sea Nazaret o Cafarnaún el pueblo natal, Jesús procedería de Galilea, una región situada al norte del actual Israel en la que se daba una enorme mezcla de población, por lo que los judíos más ortodoxos la consideraban pagana (de ahí su nombre de Galilea de los gentiles, es decir, de los no judíos). Además, Galilea tenía fama de estar habitada por gente con gran sentido de la independencia y difícil de gobernar, y allí habían surgido, y surgirían en el futuro, numerosos movimientos revolucionarios de liberación.

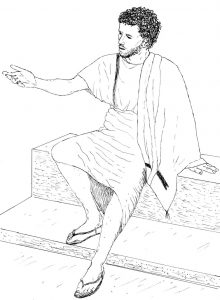

Volviendo a la pregunta inicial, y teniendo en cuenta la información (a veces contradictoria, y casi nunca con verdadera intención historiográfica, sino más bien teológica) que nos ofrecen los evangelios, creo que si Jesús hubiera tenido que responder al soldado romano de nuestra escena imaginaria, habría respondido lo siguiente:

¿Nombre?

Yeshua bar Yosef.

¿Fecha de nacimiento?

Aproximadamente en el año 3753 desde la creación del mundo, que fue el trigésimo tercer año de reinado de Herodes en Judea, y también el vigésimo año del imperio del emperador Octaviano Augusto en Roma (7 a. C.)

¿Lugar de nacimiento?

Nazaret, Galilea.

Autor

Javier Alonso López – Licenciado en Filología Semítica (hebreo y arameo), DEA en Historia Antigua y Máster en lenguas y culturas del Oriente Próximo Antiguo, todo por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Profesor de la IE University, autor de varios libros sobre religiones e historia, en especial sobre judaísmo y mundo cristiano primitivo.

Fonte: Mediterráneo Antiguo – 23 diciembre, 2015

![FRITZ, V. et al. (eds.) Prophet und Prophetenbuch: Festschrift für Otto Kaiser zum 65. Geburtstag. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, [1989] 2012 FRITZ, V. et al. (eds.) Prophet und Prophetenbuch: Festschrift für Otto Kaiser zum 65. Geburtstag. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, [1989] 2012](https://airtonjo.com/blog1/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/volkmarfritz-2-189x300.jpg)