Arqueólogos israelenses encontram a primeira frase completa escrita em cananeu. Em um pente para remover piolhos.

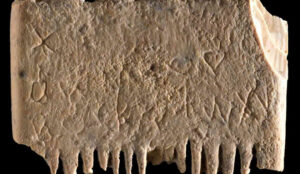

Os piolhos eram uma praga na antiguidade, como são até hoje. Sabemos disso porque arqueólogos israelenses encontraram um pente para remoção de piolhos cananeu feito de marfim e que pode ser datado por volta de 1700 a.C.

Encontrado em 2017 na cidade de Laquis, o artefato tem 17 letras formando sete palavras em proto-cananeu: “Que esta presa arranque os piolhos do cabelo e da barba”.

O pente foi estudado por pesquisadores da Universidade Hebraica de Jerusalém, bem como da Universidade Adventista do Sul e da Universidade Lipscomb, ambas no Tennessee. O projeto foi dirigido pelos professores Yosef Garfinkel, Michael Hasel e Martin Klingbeil, e o pente foi limpo e preservado por Miriam Lavi.

Tennessee. O projeto foi dirigido pelos professores Yosef Garfinkel, Michael Hasel e Martin Klingbeil, e o pente foi limpo e preservado por Miriam Lavi.

Mas a inscrição foi notada apenas este ano pela pesquisadora Madeleine Mumcuoglu, da Universidade Hebraica de Jerusalém. A escrita foi decifrada pelo epigrafista Daniel Vainstub da Universidade Ben-Gurion em Be’er Sheva. Suas descobertas foram publicadas no Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology.

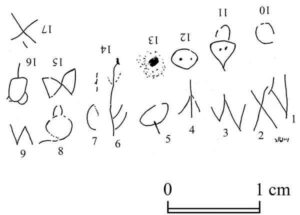

“O pente tem apenas 3 centímetros de comprimento e cada letra tem cerca de 2 a 3 milímetros de tamanho, e eles foram talhados muito superficialmente”, diz Garfinkel. “Sob luz normal, a inscrição não era visível. Mas depois de seis anos foi examinado novamente, talvez graças à luz lateral – e de repente a inscrição foi vista.”

O pente inscrito tem seis dentes grandes de um lado, para desembaraçar o cabelo ou a barba, e 14 dentes mais finos do outro lado que podem prender os parasitas e seus ovos, também conhecidos como lêndeas.

Quem poderia ter possuído um artefato como aquele na Idade do Bronze?

O marfim era um item de luxo. O marfim do pente provavelmente foi importado do Egito, sugerindo que o proprietário era rico, diz Garfinkel. “Teria sido como um diamante hoje, um item de luxo. Outros provavelmente também tinham pentes para remover piolhos, mas feitos de madeira que teria se deteriorado”, diz ele, acrescentando que o marfim, sendo osso, resistiu ao tempo. Outros pentes para piolhos foram encontrados em Laquis e em toda Canaã. Vinte foram encontrados em apenas um cemitério do Bronze Médio em Jericó, feitos de madeira.

Para ser claro, isso está longe de ser a primeira inscrição proto-cananeia encontrada em Israel: 10 foram encontradas apenas em Laquis, uma importante cidade-estado cananeia do segundo milênio a.C., a Idade do Bronze, até o início do período helenístico. Escrever em Laquis é “bem atestado” em vários períodos, observa o renomado epigrafista Christopher Rollston da George Washington University em Washington, DC, (que não esteve envolvido nesta pesquisa). Mas esta é a primeira frase cananeia completa.

A inscrição também contém a representação mais antiga conhecida da letra “sin”, que em hebraico hoje é pronunciada da mesma forma que “samekh”, ou a letra “s”, mas tinha um som diferente.

Rollston confirma que, em sua opinião, a escrita é de fato escrita cananeia primitiva, acrescentando: “Esta é uma inscrição maravilhosa, tanto por causa do conteúdo da inscrição quanto pelo objeto sobre o qual está escrita: um pente”.

Israeli Archaeologists Find First Whole Sentence Written in Canaanite. On a Lice Comb

(…) Israeli archaeologists have found a Canaanite lice comb made of elephant ivory around 3,700 years ago.

Found in 2017 in the biblical city of Lachish, the artifact joins the pantheon of ancient combs assumed to be for lice that have been found up and down the Holy Land. But this one is different.

Found in 2017 in the biblical city of Lachish, the artifact joins the pantheon of ancient combs assumed to be for lice that have been found up and down the Holy Land. But this one is different.

This one bears the earliest sentence ever found in Israel, seven words in the world’s first alphabet, archaic proto-Canaanite: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.”

(…)

The comb was unearthed and studied by researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, as well as from Southern Adventist University and Lipscomb University, both in Tennessee. The project was directed by professors Yosef Garfinkel, Michael Hasel and Martin Klingbeil, and the comb was cleaned and preserved by Miriam Lavi.

But the exhortation was noticed only this year by research associate Madeleine Mumcuoglu at Hebrew University. The writing was deciphered by semitic epigraphist Daniel Vainstub of Ben-Gurion University in Be’er Sheva. Their findings were published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology.

“The whole thing is just 3 centimeters [1.2 inches] long and each letter is about 2 to 3 millimeters in size, and they were very shallowly incised,” Garfinkel says. ”Under ordinary light the inscription wasn’t visible. But after six years it was examined again, maybe thanks to light from the side – and suddenly the inscription was observed.”

The inscribed comb has six big teeth on one side, to untangle hair or a beard, and 14 finer teeth on the other side that could snag the parasites and their eggs, aka nits, Mumcuoglu reported in 2008. All the teeth were broken in antiquity and the middle of the comb became eroded, maybe because it had been gripped tightly while being dragged through the offending locks.

The source material, tusk, was determined through analysis by Prof. Rivka Rabinovich of Hebrew University and Prof. Yuval Goren of Ben-Gurion University. Who might have owned an artifact like that in the Bronze Age?

Then as now, ivory was a luxury item. Earlier this year archaeologists excavating in Jerusalem found small ivory panels that would have adorned expensive, possibly royal, furniture.

The ivory for the comb was likely imported from Egypt, suggesting that the infested owner was wealthy, Garfinkel says. “It would have been like a diamond today, a crème de la crème luxury item. Others likely had lice combs too, but made of wood that would have decayed,” he says, adding that the ivory, being bone, weathered the ages.

(…)

To be clear, this is far from the first proto-Canaanite inscription found in Israel: 10 have been found just at Lachish, a major Canaanite city-state from the second millennium B.C.E., the Bronze Age, to the early Hellenistic period. Writing at Lachish is “nicely attested” from various periods, notes the renowned epigrapher Christopher Rollston of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., (who was not involved in this research). But this is the first actual Canaanite sentence, says Vainstub.

The inscription also contains the earliest known representation of the letter “sin”, which in hebrew today is pronounced the same as “samekh”, or the letter “s” but then had a different sound, Vainstub explains. Today the ancient sin persists only among some peoples in southern Arabia, he adds.

How did he interpret the words for louse, hair and beard? Canaanite has significant similarities with the most ancient stratum of biblical-era Hebrew, for one thing. “The first word is the root natash which serves like in Hebrew – to root out,” he explains. The Canaanite word for hair is se’ar, the same as in all semitic languages. Beard is zakat, similar to the Hebrew zakan. Though at about 3,700 years old, the Canaanite comb predates the Israelites’ arrival by centuries.

Rollston confirms that in his opinion, the writing is indeed early Canaanite script, adding: “This is a wonderful inscription, both because of the content of the inscription as well as the object upon which it is written: a comb”.

(…)

To be clear, several inscriptions in proto-Canaanite have been found to date, including 10 in Lachish itself, but all had only isolated letters or two or three words. One vessel, the “Lachish ewer” (found in 1934), bears drawings of animals and trees, and some writing; it seems to date to the late 13th century B.C.E. A shard with letters found at Lachish came from of a pot imported from Cyprus about 3,500 years ago and inked in Canaan.

Unlike the exhortation to the god against parasites, it’s too incomplete to hazard a guess at what it said. Other examples of proto-Canaanite writing were found at Gezer and Shechem.

Fonte: Haaretz – By Ruth Schuster: Nov 9, 2022.