Um longo artigo sobre o caso do fragmento do evangelho de Marcos, que causou furor entre os estudiosos da área porque andaram dizendo que era do século I. Na verdade foi escrito entre 150 e 250 d.C.

Para entender o caso, leia antes o post Ainda sobre o fragmento de Marcos, publicado em 02/07/2019.

Um escândalo em Oxford: o curioso caso do evangelho roubado

A scandal in Oxford: the curious case of the stolen gospel – Charlotte Higgins: The Guardian – Thu 9 Jan 2020

What links an eccentric Oxford classics don, billionaire US evangelicals, and a tiny, missing fragment of an ancient manuscript? Charlotte Higgins unravels a multimillion-dollar riddle

To visit Dr Dirk Obbink at Christ Church college, Oxford, you must first be ushered by a bowler-hatted porter into the stately Tom Quad, built by Cardinal Wolsey before his spectacular downfall in 1529. Turn sharp right, climb a flight of stairs, and there, behind a door on which is pinned a notice advertising a 2007 college arts festival, you will find Obbink’s rooms. Be warned: you may knock on the door in vain. Since October, he has been suspended from duties following the biggest scandal that has ever hit, and is ever likely to hit, the University of Oxford’s classics department.

An associate professor in papyrology and Greek literature at Oxford, Obbink occupies one of the plum jobs in his field. Born in Nebraska and now in his early 60s, this lugubrious, crumpled, owlish man has “won at the game of academia”, said Candida Moss, professor of theology at Birmingham University. In 2001, he was awarded a MacArthur “genius” award for his expertise in “rescuing damaged ancient manuscripts from the ravages of nature and time”. Over the course of his career, he has received millions in funding; he is currently, in theory at least, running an £800,000 project on the papyrus rolls carbonised by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79.

Since he was appointed in 1995, Obbink has welcomed many visitors into his rooms at Christ Church: dons, undergraduates, researchers. Less orthodox callers, too: among them, antiquities dealers and collectors. In the corner of Obbink’s study stands a pool table, from which two Egyptian mummy masks stare out impenetrably. Its green baize surface is all but obscured by papers and manuscripts – even, sometimes, a folder or two containing fragments of ancient papyrus. One bibliophile remembers a visit to this room, “like the set of an Indiana Jones movie”, a few years ago. He was offered an antique manuscript for sale by a man named Mahmoud Elder, with whom Obbink owned a company, now dissolved, called Castle Folio.

One blustery evening towards the end of Michaelmas term, 2011, two visiting Americans climbed Obbink’s staircase – Drs Scott Carroll and Jerry Pattengale. Both worked for the Greens, a family of American conservative evangelicals who have made billions from a chain of crafting stores called Hobby Lobby. At the time, the family was embarking on an ambitious new project: the Museum of the Bible, which opened in Washington DC in 2017. Carroll was then its director. Items for the Green collection were bought by Hobby Lobby, then donated to the museum, bringing a substantial tax write-off. Pattengale was the head of the Green Scholars Initiative, a project offering academics research opportunities on items in the Green collection.

The Greens, advised by Carroll, were buying biblical artefacts, such as Torahs and early papyrus manuscripts of the New Testament, at a dizzying pace: $70m was spent on 55,000 objects between 2009 and 2012, Carroll claimed later. The market in a hitherto arcane area of collecting sky-rocketed. “Fortunes were made. At least two vendors who had been making €1-2m a year were suddenly making €100-200m a year,” said one longtime collector.

That wintry evening, Carroll and Pattengale were making one of their occasional trips to seek Obbink’s expertise on matters papyrological. According to Pattengale, just as they were about to leave, Obbink reached into a manila envelope and pulled out four papyrus fragments, one from each of the gospels. Obbink told them that three of these scraps dated from the second century AD.

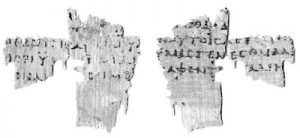

But the fourth, a fragment of the Gospel of Mark – a 4cm by 4cm scrap the shape of a butterfly’s wing, containing just a few broken words – was earlier than that. It was almost certainly from the first century AD, which would make it the oldest surviving manuscript of the New Testament, copied less than 30 years after Mark had actually written it. Conservative evangelicals place enormous weight on the Gospels as “God-breathed” words. The idea that such an object existed was indescribably thrilling. Carroll was “ecstatic”, Pattengale recalled. “Veins along his neck bulged. He paced with arms flailing.”

almost certainly from the first century AD, which would make it the oldest surviving manuscript of the New Testament, copied less than 30 years after Mark had actually written it. Conservative evangelicals place enormous weight on the Gospels as “God-breathed” words. The idea that such an object existed was indescribably thrilling. Carroll was “ecstatic”, Pattengale recalled. “Veins along his neck bulged. He paced with arms flailing.”

Carroll, who declined to be interviewed, has said that Pattengale’s account is full of “misrepresentations, misrecollections, and exaggerations”. But he has confirmed this: Obbink showed him the Mark fragment “on the pool table in his office … and he then went into some paleographic detail why he believed it must date to the late-first century … It was in this conversation that he offered it for consideration for Hobby Lobby to buy.”

No purchase was made at the time. Nevertheless, the objects did eventually end up being sold to the Greens, after Carroll left their employ in 2012. The vendor, or so it appears, was Dirk Obbink. His name, and seemingly his signature, appear on a purchase agreement with Hobby Lobby dated 4 February 2013.

The problem is that the items – if the purchase agreement is genuine – were not Obbink’s to sell. They are part of the Oxyrhynchus collection of ancient papyrus, owned by the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) and housed at Oxford’s Sackler Library.

Thirteen additional fragments from the collection, it transpired this autumn, had also been sold to the Greens, 11 apparently by Obbink in 2010, and two by a Jerusalem-based antiquities dealer, Baidun & Sons. (A spokesperson for the company’s owner, Alan Baidun, says he was an agent acting in good faith, and that he checked the provenance supplied by the person who sold them to him.)

Six further fragments from the Oxyrhynchus collection have turned up in the possession of another collector in the US, Andrew Stimer, a spokesperson for whom says he acquired them in good faith, and with an apparently complete provenance (though parts of it have subsequently been shown to have been falsified). The dealer who sold them to Stimer told him they had come from the collection of M Elder of Dearborn, Michigan. That is, Mahmoud Elder, Obbink’s sometime business partner. (Elder did not respond to requests for comment. Both the Museum of the Bible and Stimer have cooperated fully with the EES, and have taken steps to return the fragments.)

In total, the EES has now discovered that 120 fragments have gone missing from the Oxyrhynchus collection over the past 10 years. Since the appearance, in June 2019, of that fateful purchase agreement and invoice bearing Obbink’s name, the scale of the scandal has taken time to sink in. What kind of a person – what kind of an academic – would steal, sell, and profit from artefacts in their care? Such an act would be “the most staggering betrayal of the values and ethics of our profession”, according to the Manchester University papyrologist Roberta Mazza.

The alleged thefts were reported to Thames Valley police on 12 November. No one has yet been arrested or charged. Obbink has not responded to interview requests from the Guardian, and has issued only one public statement. “The allegations made against me that I have stolen, removed or sold items owned by the Egypt Exploration Society collection at the University of Oxford are entirely false,” he has said. “I would never betray the trust of my colleagues and the values which I have sought to protect and uphold throughout my academic career in the way that has been alleged. I am aware that there are documents being used against me which I believe have been fabricated in a malicious attempt to harm my reputation and career.”

It seems that Dr Dirk Obbink is either a thief, has been caught up in a colossal misunderstanding, or, perhaps most shockingly of all, is the victim of an elaborate effort to frame him (continua).

Quem quiser ver apenas os pontos relevantes, pode ler o post de Peter Gurry, Longform Guardian Article on the Mark Fragment Saga, publicado hoje no blog Evangelical Textual Criticism.