Reproduzo aqui alguns trechos do livro de THELLE, R. Discovering Babylon. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019, p. 77-83.

Li o capítulo V do livro e gostei bastante do relato sobre a descoberta arqueológica da antiga Mesopotâmia.

Estes trechos traduzidos são deste capítulo e contam a história da escavação da cidade de Babilônia por Robert Koldewey, de 1899 a 2017.

As notas de rodapé (números 14-32) foram omitidas. O original inglês vem logo após a tradução em português.

A cidade de Babilônia

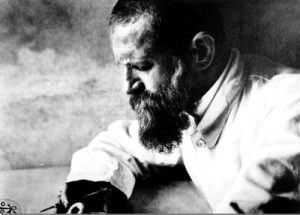

Em 1887 um arquiteto alemão chamado Robert Koldewey viajou para a Babilônia junto com o arabista Bruno Moritz e H.F. Ludwig Meyer, um comerciante. Koldewey já havia participado como arquiteto na escavação americana de Assos na costa oeste da Turquia (1882-1883) e em 1885-1886 escavou na ilha de Lesbos em nome do Instituto Imperial Alemão de Arqueologia. Na viagem pelo sul do Iraque, Moritz e Koldewey realizaram escavações experimentais em Surghul e El-Hibba (Lagash), mas Koldewey não ficou impressionado. Muitos anos depois, ele comentou que se alguém lhe tivesse dito em 1887 que 20 anos depois ele escavaria a cidade de Babilônia, ele teria pensado que eles eram loucos.

havia participado como arquiteto na escavação americana de Assos na costa oeste da Turquia (1882-1883) e em 1885-1886 escavou na ilha de Lesbos em nome do Instituto Imperial Alemão de Arqueologia. Na viagem pelo sul do Iraque, Moritz e Koldewey realizaram escavações experimentais em Surghul e El-Hibba (Lagash), mas Koldewey não ficou impressionado. Muitos anos depois, ele comentou que se alguém lhe tivesse dito em 1887 que 20 anos depois ele escavaria a cidade de Babilônia, ele teria pensado que eles eram loucos.

Dez anos depois, após ter concluído vários outros projetos, Koldewey foi convidado a participar de uma pré-expedição à Mesopotâmia em busca de locais apropriados para as escavações alemãs. Nesta viagem, ele foi acompanhado pelo orientalista Eduard Sachau. Durante um período de seis meses, eles cobriram a área da Índia no leste ao Egito no oeste, de Aden no sul até Khorsabad e Aleppo no norte. No local da antiga Babilônia, eles encontraram vários fragmentos de tijolos vitrificados coloridos. Além de ser um linguista de línguas semíticas, Sachau era um especialista no estudioso muçulmano Al-Biruni, que viveu no século XI no atual Afeganistão e na Índia. Quando Sachau e Koldewey apresentaram suas descobertas perante a comissão em Berlim, Babilônia foi escolhida como o local para escavar, e Koldewey foi contratado para dirigir a escavação.

Chegam os alemães: escavando Babilônia

No final, foram os fragmentos de tijolos vitrificados coloridos que os franceses também descreveram quase 50 anos antes que convenceram as autoridades alemãs de que Babilônia merecia se tornar o foco de um grande projeto. Esta foi a primeira escavação em grande escala da Alemanha na Mesopotâmia. Em comparação com a Inglaterra e a França, os exploradores alemães procuravam objetos para seus museus nacionais no Oriente Médio há pouco tempo. Embora eles tivessem começado a explorar o Egito, a Grécia e algumas partes da Turquia, como Troia e até a Palestina em 1899, eles não o haviam feito na Mesopotâmia.

Desde a primeira época de descobertas em Nínive entre 1842 e 1852, grandes mudanças também aconteceram na Europa no cenário político. A Alemanha foi unificada como nação em 1871, após a guerra franco-prussiana. No início, a Alemanha, sob o chanceler Bismarck, optou por uma política externa bastante moderada que mantinha o equilíbrio de poder na Europa. Mas com o imperador Wilhelm II, uma nova época começou. Wilhelm II substituiu Bismarck por outro chanceler dois anos após sua ascensão ao trono imperial em 1888, e começou um período caracterizado por uma política externa cada vez mais ampliada que ele chamou de Weltpolitik. A Alemanha desenvolveu fortes laços com o Império Otomano, o que os ajudou a garantir boas condições para as escavações. A construção da ferrovia Berlim-Bagdá é um exemplo das grandes ambições do Império Alemão na Ásia Ocidental, o que acabou prejudicando seu relacionamento com a Rússia, França e Inglaterra.

Quando a escavação de Babilônia começou em 1899, os métodos arqueológicos já eram muito mais desenvolvidos e refinados do que quando Botta e Layard cavaram túneis para obter esculturas de pedra 50 anos antes. Além disso, em comparação com as escavações de Nippur e Lagash (Girshu-Telloh), a expedição alemã foi muito mais cuidadosa e sistemática. De muitas maneiras, a escavação da Babilônia estabeleceu o padrão para a metodologia arqueológica moderna. Além disso, como Koldewey era arquiteto, ele dirigiu a escavação sabendo como era importante obter uma visão geral da extensão dos edifícios e documentar o plano da cidade. Os métodos empregados na escavação da Babilônia passaram a servir de modelo para a metodologia de escavação nas ruínas desta área. O termo tell é usado para falar dessas elevações no Oriente Médio. Vem do hebraico e refere-se a uma colina artificial que é o resultado de séculos de camadas de ocupação humana. Os métodos usados pelo pessoal de Koldewey foram transmitidos de geração em geração de trabalhadores contratados localmente, levando ao desenvolvimento de técnicas especializadas para localizar muralhas e traçar os contornos de edifícios nos tijolos de barro antigos e delicados ou nos tijolos secos ao sol. Foi dada atenção à estratigrafia (um método que requer a documentação das várias camadas de terra através das quais se cava) e à documentação do contexto de pequenos achados. As escavações no Iraque após a Primeira Guerra Mundial seguiram o que passou a ser chamado de “método alemão”, quer fossem lideradas por americanos, britânicos ou outros.

Quando a escavação de Babilônia começou em 1899, os métodos arqueológicos já eram muito mais desenvolvidos e refinados do que quando Botta e Layard cavaram túneis para obter esculturas de pedra 50 anos antes. Além disso, em comparação com as escavações de Nippur e Lagash (Girshu-Telloh), a expedição alemã foi muito mais cuidadosa e sistemática. De muitas maneiras, a escavação da Babilônia estabeleceu o padrão para a metodologia arqueológica moderna. Além disso, como Koldewey era arquiteto, ele dirigiu a escavação sabendo como era importante obter uma visão geral da extensão dos edifícios e documentar o plano da cidade. Os métodos empregados na escavação da Babilônia passaram a servir de modelo para a metodologia de escavação nas ruínas desta área. O termo tell é usado para falar dessas elevações no Oriente Médio. Vem do hebraico e refere-se a uma colina artificial que é o resultado de séculos de camadas de ocupação humana. Os métodos usados pelo pessoal de Koldewey foram transmitidos de geração em geração de trabalhadores contratados localmente, levando ao desenvolvimento de técnicas especializadas para localizar muralhas e traçar os contornos de edifícios nos tijolos de barro antigos e delicados ou nos tijolos secos ao sol. Foi dada atenção à estratigrafia (um método que requer a documentação das várias camadas de terra através das quais se cava) e à documentação do contexto de pequenos achados. As escavações no Iraque após a Primeira Guerra Mundial seguiram o que passou a ser chamado de “método alemão”, quer fossem lideradas por americanos, britânicos ou outros.

A escavação da Babilônia foi o primeiro projeto da recém-formada Sociedade Oriental Alemã (Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft). Representantes dos Museus Reais de Berlim foram os comissários do projeto. Eles negociaram com as autoridades otomanas para obter as autorizações necessárias, contrataram Koldewey como diretor e deram à Sociedade Oriental Alemã a responsabilidade de supervisionar o projeto. Inicialmente, o empresário judeu James Simon disponibilizou o financiamento, que mais tarde foi continuado pelo próprio imperador. Simon era um personagem importante na Berlim da época; ele dirigia uma das maiores empresas de algodão da Europa e era o maior contribuinte de Berlim. Ele também apoiava a expansão da cultura alemã e era amigo do imperador Wilhelm. Simon dirigia muitos projetos filantrópicos para judeus na Alemanha e apoiava a presença judaica na Palestina.

A Porta de Ishtar, a Via Processional e o Templo de Marduk

Os restos encontrados pelos escavadores de Babilônia vieram principalmente do último período de grandeza da Babilônia, quando ela era o centro do império de Nabucodonosor II no século VI a.C. Nabucodonosor restaurou Babilônia ao seu antigo status de maior cidade do Oriente Médio. Essa foi a Babilônia que ameaçou, destruiu e devastou Jerusalém, pondo fim à monarquia da Judeia. Os escavadores também encontraram vestígios da primeira Babilônia, a cidade que fora a capital do primeiro reino real na Mesopotâmia – o Antigo Reino da Babilônia – com Hammurabi como seu rei mais famoso (1792–1750 a.C).

A descoberta mais espetacular da expedição alemã foi a Porta de Ishtar com a Via Processional que atravessa a porta e entra na cidade. Os pedaços de tijolos vitrificados coloridos que foram encontrados anteriormente vieram dessas estruturas. E as muralhas da cidade acabaram sendo tão maciças quanto Heródoto havia afirmado. As muralhas de Babilônia formavam um complexo sistema defensivo com uma muralha externa e outra interna, com espessura total de 22 metros. Em alguns lugares, as muralhas incluíam outras estruturas defensivas, tornando sua espessura ainda mais próxima da medida de Heródoto de 26 metros.

Os escavadores começaram com a maior elevação, chamado Kasr, o “monte do palácio”. Eles fizeram uma trincheira a partir do leste e estabeleceram uma ligação com a Via Processional, que corria na direção sul da Porta de Ishtar, ao longo do lado leste deste enorme complexo palaciano. No monte Kasr, os escavadores descobriram um dos palácios de Nabucodonosor, o Palácio Sudoeste, o maior edifício da Babilônia. Uma das salas do Palácio Sudoeste era a sala do trono de Nabucodonosor, cujas paredes também haviam sido cobertas com tijolos vitrificados e decorações coloridas. No canto noroeste do palácio, os escavadores descobriram um edifício com muitos arcos. Koldewey sugeriu que este poderia ser o local dos Jardins Suspensos da Babilônia.

A Porta de Ishtar foi completamente escavada apenas em 1909-1910. Descobriu-se que tinha sido construída em várias etapas. A camada superior, construída por Nabucodonosor, consistia em tijolos cobertos por esmalte colorido e era parcialmente visível acima do atual nível do solo. Sob o solo, havia restos de uma camada intermediária e um nível inferior completamente preservado. Os níveis inferiores da porta foram construídos em tijolos, com relevos de touros e uma criatura parecida com um dragão – chamada de mushhushu. Esses animais foram associados a dois dos deuses mais importantes da Babilônia: o touro com o deus da tempestade Adad e a criatura dragão com o deus da cidade da Babilônia, Marduk. Nabucodonosor havia construído sua porta sobre as fundações de construções anteriores.

Nabucodonosor, consistia em tijolos cobertos por esmalte colorido e era parcialmente visível acima do atual nível do solo. Sob o solo, havia restos de uma camada intermediária e um nível inferior completamente preservado. Os níveis inferiores da porta foram construídos em tijolos, com relevos de touros e uma criatura parecida com um dragão – chamada de mushhushu. Esses animais foram associados a dois dos deuses mais importantes da Babilônia: o touro com o deus da tempestade Adad e a criatura dragão com o deus da cidade da Babilônia, Marduk. Nabucodonosor havia construído sua porta sobre as fundações de construções anteriores.

Koldewey e sua equipe descobriram que a Via Processional havia sido elevada várias vezes, devido ao aumento contínuo das águas subterrâneas. A inundação é a principal razão pela qual resta tão pouco da cidade da Antiga Babilônia, da época de Hammurabi. Algumas seções do nível neobabilônico da Via Processional foram pavimentadas com grandes pedras de calcário colocadas em um material semelhante ao asfalto chamado betume (o material descrito na história bíblica da Torre de Babel). Imediatamente ao sul da Porta de Ishtar, algumas dessas pedras ainda estavam intactas. Em seguida, a rua cruzava uma área frequentemente inundada por águas que corriam para oeste até o braço do Eufrates. Nabucodonosor restaurou este trecho da rua, incluindo os sistemas de canais que levavam a água a fluir ao redor do Palácio Sul. Mais adiante, ao sul do monte Kasr, uma parte da rua pavimentada com calcários duros ainda estava intacta, com inscrições de Nabucodonosor. Alguns deles tinham o nome do rei assírio Senaquerib por baixo, e haviam sido reutilizados por Nabucodonosor. Senaquerib claramente acrescentou melhorias à cidade que acabou arrasando e, dessa forma, deixou sua marca em Babilônia quando a conquistou cerca de 100 anos antes da época de Nabucodonosor. Onde corre ao longo das muralhas externas do complexo Etemenanki (o complexo que incluía o antigo zigurate), a Via Processional tinha camadas de tijolos cozidos com o carimbo de Nabucodonosor. Koldewey descreve uma inscrição de construção que encontraram, afirmando que Nabucodonosor havia construído a via e dando uma data para a atividade de construção.

Os fragmentos de tijolos vitrificados que convenceram os financiadores a realizar escavações em Babilônia vieram dos relevos de touro e mushhushu da Porta de Ishtar, e também de relevos de leão que decoraram as muralhas paralelas ao longo da Via Processional. O leão era o símbolo da deusa Ishtar.

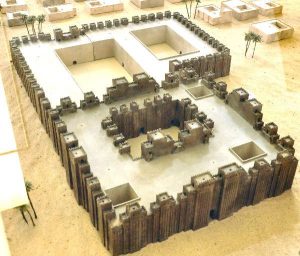

A maior elevação de Babilônia, com mais de 25 metros, tinha o nome de Tel Amran Ibn Ali e ficava a uma curta distância ao sul de Kasr. Neste monte estavam os restos do edifício mais importante da Babilônia, o Eságil, o templo de Marduk. Eságil é sumério e significa “a casa da cabeça erguida”. A elevação envolveu a escavação de poços através de mais de 20 metros de entulho e a remoção de enormes quantidades de entulho. O templo principal é quase quadrado, medindo aproximadamente 80 por 86 metros e com um pátio interno de cerca de 30 por 38 metros. Um dos edifícios mais antigos da Babilônia, partes dele podem ser datadas da época do Rei Hammurabi no período da Antiga Babilônia. O complexo do templo havia sido restaurado por Nabucodonosor e também continha pelo menos dois outros templos, talvez um para o deus Ea.

Entre Kasr e o Eságil estavam os restos do zigurate da Babilônia, o Etemenanki, “a casa do fundamento do céu e da terra”. Provavelmente era uma torre de sete ou oito andares, o edifício que inspirou a narrativa da Torre de Babel (Gn 11). O Etemenanki ficava dentro de uma grande construção retangular de tijolos, que incorporava vários edifícios associados à torre. Podem ter sido depósitos, salas para reuniões públicas e aposentos para os sacerdotes e outras pessoas associadas ao complexo do templo. Chegava-se a esta área por um portão na muralha leste do recinto, que fornecia uma entrada pela Via Processional. Em direção ao sul provavelmente havia uma porta que levava ao Eságil, que ficava a cerca de 251 metros ao sul do complexo Etemenanki.

No início, George Smith descreveu um texto descoberto na cidade de Uruk, no sul, que fala do Etemenanki. Este texto fala de uma torre de sete andares. O texto foi usado para orientar o trabalho de escavação e interpretação na Babilônia; infelizmente, porém, acabou não sendo de muita ajuda. Além disso, o texto real havia se perdido na época em que a escavação estava em andamento, e Koldewey e seu pessoal só tinham a descrição temporária feita por George Smith. Existem outros textos que descrevem os edifícios e bairros de Babilônia. Às vezes, isso gerou mais confusão do que clareza, mas também forneceu informações que ajudaram na identificação de estruturas e na elaboração de um plano da cidade.

Koldewey escavou vários outros templos na Babilônia, uma cidade que pode ter tido mais de 100 templos, incluindo os templos de Nabu, Ishtar e Ninmah. Os escavadores também investigaram uma área residencial e descobriram partes das maciças muralhas externas e internas da Babilônia. Cerca de 400 metros ao norte da Porta de Ishtar, fora das muralhas internas da cidade, mas dentro das muralhas externas, o Palácio de Verão dos reis neobabilônicos também foi escavado.

A escavação alemã forneceu uma visão geral detalhada da planta de uma antiga cidade mesopotâmica, disponibilizando essas informações pela primeira vez. Os novos métodos que os alemães desenvolveram permitiram traçar os contornos de edifícios e paredes construídas com tijolos crus de argila. Nenhuma escavação anterior havia registrado todas as descobertas com tanto cuidado. Os achados foram numerados, seu contexto anotado e tudo foi desenhado ou fotografado. Nos primeiros anos da escavação, especialistas em cuneiforme também participaram. Mais tarde, o próprio Koldewey assumiu a responsabilidade pelos achados textuais, que somam cerca de 5.000 tabuinhas. As escavações continuaram virtualmente sem interrupção por 17 anos, de 1899 a 1917. O próprio Koldewey permaneceu no Iraque continuamente desde o início em 1899. Após a derrota alemã na Primeira Guerra Mundial, a Grã-Bretanha assumiu o poder na região e os alemães tiveram que se retirar de Babilônia.

The city of Babylon

In 1887 a German architect by the name of Robert Koldewey journeyed to Babylon together with the Arabist Bruno Moritz and H.F. Ludwig Meyer, a merchant. Koldewey had previously participated as an architect in the American excavation of Assos on the west coast of Turkey (1882–1883) and in 1885–1886 had dug on the island of Lesbos on behalf of the German Imperial Institute of Archaeology. On the trip around the south of Iraq, Moritz and Kodelwey conducted trial digs in Surghul and El-Hibba (Lagash), but Koldewey was not impressed. Many years later he commented that if anyone had told him in 1887 that 20 years later he would be excavating Babylon he would have thought that they were insane.

Ten years later, after he had completed several other projects, Koldewey was invited to join a pre-expedition to Mesopotamia to look for appropriate places for German excavations. On this trip he was joined by the Orientalist Eduard Sachau. Over a period of six months, they covered the area from India in the east to Egypt in the west, from Aden in the south to Khorsabad and Aleppo to the north. At the site of ancient Babylon, they had come across numerous fragments of colored glaze. In addition to being a linguist of Semitic languages, Sachau was an expert on the Muslim scholar Al-Biruni, who had lived in the 11th century in present-day Afghanistan and India. When Sachau and Koldewey presented their findings before the commission in Berlin, Babylon was chosen as the place to excavate, and Koldewey was commissioned to direct the excavation.

The Germans arrive: excavating Babylon

In the end, it was the fragments of colored glazed brick that the French had also described almost 50 years earlier that convinced the authorities that Babylon deserved to become the focus of a major project. This was Germany’s fi rst large-scale excavation in Mesopotamia. Compared to England and France, German explorers had been searching for objects for their national museums in the Middle East only for a short time. While they had begun to explore in Egypt, Greece, and some parts of Turkey, such as Troy, and even Palestine by 1899, they had not done so in Mesopotamia.

In the time since the first epoch of discoveries in Nineveh between 1842 and 1852, major changes had also happened in Europe on the political stage. Germany had been unifi ed as a nation in 1871 following the Franco-Prussian war. At first, Germany, under Chancellor Bismarck, chose a fairly restrained foreign policy which maintained the balance of power in Europe. But with Emperor Wilhelm II, a new epoch began. Wilhelm II replaced Bismarck with another chancellor two years after he ascended to the Imperial throne in 1888, and a period began characterized by an increasingly expansive foreign policy that he called Weltpolitik . Germany developed strong ties to the Ottoman Empire, which aided them in securing good terms for excavations. The building of the Berlin–Baghdad Railroad is one example of the German Empire’s great ambitions in Western Asia, which eventually came to damage its relationship with Russia, France, and England.

When the excavation of Babylon began in 1899, archaeological methods were much more developed and refi ned than they had been when Botta and Layard tunneled for stone reliefs over 50 years earlier. Further, compared to the excavations of Nippur and Lagash (Girshu-Telloh), the German expedition was much more careful and systematic. In many ways, the excavation of Babylon came to set the standard for modern archaeological methodology. In addition, because Koldewey was an architect, he directed the excavation with an understanding of how important it was to get an overview of the extent of the buildings and to document the city plan. The methods employed in the Babylon excavation came to serve as the model for excavation methodology in the ruin mounds of this area. The term tell is used to speak of these mounds in the Middle East. It comes from the Hebrew (Arabic tal ) and refers to an artificial mound that is the result of centuries of layers of human occupation. The methods used by Koldewey’s people were passed down from generation to generation of workers who were locally hired, leading to the development of specialized techniques for finding walls and tracing the contours of buildings in the ancient, delicate mudbrick or sun-dried bricks. Attention was paid to stratigraphy (a method which requires documentation of the various layers of earth through which one digs) and to documenting the context of small fi nds. Excavations in Iraq after World War I all followed what had begun to be called “the German method”, whether they were led by Americans, British, or others.

The Babylon excavation was the fi rst project of the newly formed German Oriental Society ( Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft ). Representatives of the Royal Museums of Berlin were the commissioners of the project. They negotiated with the Ottoman authorities to obtain the necessary permits, hired Koldewey as the director, and gave the German Oriental Society the responsibility of overseeing the project. Initially, the Jewish businessman James Simon put up the funding, which was later continued by the Emperor himself. Simon was a high-profi le character in contemporary Berlin; he ran one of Europe’s largest cotton businesses and was the biggest taxpayer of Berlin. He was also a supporter of expanding German culture, and a friend of Emperor Wilhelm. Simon ran many philanthropic projects for Jews in Germany and was a supporter of a Jewish presence in Palestine.

The Ishtar Gate, the Processional Way, and the temple of Marduk

The remains found by the excavators of Babylon came mainly from Babylon’s last period of greatness, when it was the center of Nebuchadnezzar II’s empire in the 6th century bce. Nebuchadnezzar restored Babylon to its former status as the greatest city in the Middle East. This was the Babylon that had threatened, destroyed, and devastated Jerusalem, bringing an end to the Judean monarchy. The excavators also found traces of the fi rst Babylon, the city that had been the capital city of the fi rst royal kingdom in Mesopotamia—The Old Babylonian Kingdom—with Hammurabi as its most famous king (1792–1750 BCE).

The German expedition’s most spectacular discovery was the Ishtar Gate with the Processional Way that leads through the gate and into the city ( Figure 5.5 ). The pieces of colored glazed brick that had been found earlier came from these structures. And the city walls turned out to be just as massive as Herodotus had claimed. The walls of Babylon made up a complex defensive system with an outer and an inner wall, with a total thickness of 24 yards. In some places the walls included further defensive structures, making their thickness even closer to Herodotus’ measurement of 28.5 yards.

Excavators began with the largest mound, called Kasr, the “palace mound”. They cut a trench from the east, and came into contact with the Processional Way, which ran in a southerly direction from the Ishtar Gate, along the eastern side of this enormous palace complex. In the Kasr mound, the excavators uncovered one of Nebuchadnezzar’s palaces—the South-West Palace—the largest building in Babylon. One of the rooms in the South-West Palace was the throne room of Nebuchadnezzar, the walls of which had also been covered with colored glaze and decorations. Off the northwestern corner of the palace, excavators uncovered a building with many arches. Koldewey suggested that this could have been the site of the Hanging Gardens.

a southerly direction from the Ishtar Gate, along the eastern side of this enormous palace complex. In the Kasr mound, the excavators uncovered one of Nebuchadnezzar’s palaces—the South-West Palace—the largest building in Babylon. One of the rooms in the South-West Palace was the throne room of Nebuchadnezzar, the walls of which had also been covered with colored glaze and decorations. Off the northwestern corner of the palace, excavators uncovered a building with many arches. Koldewey suggested that this could have been the site of the Hanging Gardens.

The Ishtar Gate was completely excavated only in 1909–1910. It turned out that it had been constructed in several layers. The top layer, which had been built by Nebuchadnezzar, consisted of bricks covered by colored glaze, and was partly visible above the present-day ground level. Under ground level, there were remains of a middle layer and a completely preserved lower level. The lower levels of the gate had been built in brick, with reliefs of bulls and a dragon-like creature—called mushhushu . These animals were associated with two of the most important gods of Babylon: the bull with the weather god Adad and the dragon creature with Babylon’s city god, Marduk. Nebuchadnezzar had built his gate on the foundations of earlier constructions.

Koldewey and his team discovered that the Processional Way had been raised several times, due to the continually rising ground water. The rising water is the main reason why there is so little left of the Old Babylonian city. Some sections of the Neo-Babylonian level of the Processional Way had been paved with large limestone stones laid down into the asphalt-like material called bitumen (the material described in the Bible’s story of the Tower). Immediately south of the Ishtar Gate some of these stones were still intact. Next, the street crossed an area often flooded by water fl owing west to the branch of the Euphrates. Nebuchadnezzar had restored this section of the street, including the channel systems that led the water to fl ow around the South Palace. Further on, south of the Kasr mound, a portion of the street paved with hard limestones were still intact, which had dedicatory inscriptions of Nebuchadnezzar. Some of these had the name of the Assyrian king Sennacherib on the underneath, and had been reused by Nebuchadnezzar. Sennacherib had clearly added improvements to the city that he ultimately razed, and had in this way set his mark on Babylon when he conquered it about 100 years before Nebuchadnezzar’s time . Where it runs along the outer walls of the Etemenanki complex (the complex that included the ancient ziggurat), the Processional Way had layers of baked bricks with Nebuchadnezzar’s stamp. Koldewey describes a building inscription they found, stating that Nebuchadnezzar had built the road and giving a date for the building activity.

The fragments of glazed brick that convinced the funders to dig in Babylon had come from the bull and mushhushu reliefs of the Ishtar Gate, and also from lion reliefs that had decorated the parallel walls along the Processional Way. The lion was the symbol of the goddess Ishtar.

The tallest mound in Babylon, standing over 25 meters, went under the name of Tel Amran Ibn Ali; it lay a short distance south of Kasr. In this mound lay the remains of the most important building in Babylon, the Esagil, the temple of Marduk. Esagil is Sumerian and means “the house of the lifted head”. Surveying it involved digging shafts down through over 20 meters of debris and removing enormous amounts of rubble. The main temple is almost quadratic, measuring approximately 80 by 86 meters and with an inner court about 30 by 38 meters. One of the oldest buildings in Babylon, parts of it may date back to the time of King Hammurabi in the Old Babylonian period. The temple complex had been restored by Nebuchadnezzar, and also contained at least two other temples, perhaps one for the god Ea.

Between Kasr and the Esagil lay the remains of Babylon’s ziggurat , the temple tower of Etemenanki, “the house of the foundation of heaven and earth”. This had likely been a tower of seven or eight stories, the inspiration for the Tower of Babel. The Etemenanki stood inside a large rectangular brick construction, that incorporated several buildings associated with the tower. These may have been storage rooms, rooms for public gatherings, and living quarters for the priests and other personnel associated with the temple complex. One arrived at this area through a gate in the eastern wall of the enclosure, which provided an entry from the Processional Way. Toward the south there had most likely been a gate which led toward the Esagil, which lay around 275 yards south of the Etemenanki complex.

Early on, George Smith had described a text discovered in the southern city of Uruk, which speaks of the Etemenanki. This text describes a tower of seven stories. The text was used to direct the work of excavating and interpreting in Babylon; unfortunately, however, it turned out not to be of much help. Moreover, the actual text had been lost by the time the excavation was underway, and Koldewey and his people only had the temporary description of it that George Smith had made. There are other texts that describe the buildings and town quarters of Babylon. These have sometimes led to confusion rather than clarity, but they have also given information that has helped in the identifi cation of structures and in delineating a plan of the city.

Koldewey excavated several other temples in Babylon, a city that may once have had over 100 temples, including the temples of Nabo, Ishtar, and Ninmah. Excavators also investigated an area of living quarters, and uncovered parts of Babylon’s massive outer and inner walls. Around one quarter of a mile north of the Ishtar Gate, outside the inner city walls but within the outer walls, the Neo-Babylonian kings’ Summer Palace was also excavated.

The German excavation provided a detailed overview of the city plan of an ancient city in Iraq, making this information available for the first time. The new methods they had developed allowed them to trace the contours of buildings and walls built with unfired clay bricks. No previous excavator had recorded all the finds so carefully before. The finds were numbered, their context noted, and everything was drawn or photographed. In the first few years of the excavation, cuneiform experts also participated. Later, Koldewey himself took on the responsibility for the textual finds, which amount to a total of around 5000 inscribed tablets. The excavations continued virtually without a break for 17 years, from 1899 to 1917. Koldewey himself stayed in Iraq continuously from the beginning in 1899–1914. After the German defeat in World War I, Great Britain took power in the newly created mandate area of Iraq, and the Germans had to pull out of Babylon.